Carl Richards is a certified financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at the BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published this year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

During my time writing for Bucks, I’ve read several comments from different people that share a common theme: “I don’t have any trouble behaving when it comes to investing. So why can’t you?”

If you fall into this group, investing and behaving may appear so simple to you that you can’t help but wonder if the rest of us are short a few brain cells. But your ability to behave is really quite remarkable.

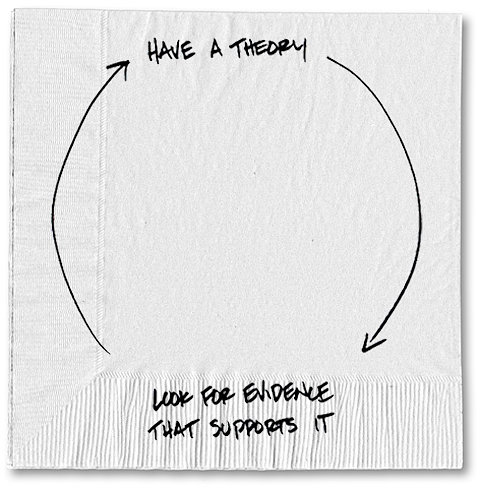

After all, as Daniel Kahneman noted in his brilliant book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” we all suffer to some extent from cognitive biases that make it nearly impossible to behave. These biases often cause us to take mental shortcuts that can thwart our efforts to successfully balance logic and emotion.

In a recent interview with Morgan Housel of The Motley Fool, Dr. Kahneman explains why some people (maybe you?) can better handle these biases. He also discusses why these biases can be so hard to avoid (the portion of the interview presented below was edited out of the video for space):

Morgan Housel: We often hear that Warren Buffett was born hard-wired for the traits that he has as an investor, which sounds nice. But I wonder if there’s any truth to that. Is there evidence that some people are more prone to cognitive biases than others?

Dr. Kahneman: Yes. There certainly are differences among people. There are differences in intelligence and there are differences in cognitive style and the degree to which people check themselves. So some people definitely are more prone to biases than others. That doesn’t mean that they are doomed to be biased. But certainly being prone to self-control and to slow thinking in general, you’ll find differences in children aged 3 or 4, and some of these differences persist into adulthood.

Morgan Housel: So most of these biases are things that we are born with; they’re not traits that we learn.

Dr. Kahneman: The biases that I’ve been concerned with are really characteristics, I think, of the way we’re wired to interpret the world. So in that sense, yes, we’re born with them. I mean we’re born to see patterns, and if seeing patterns leads you into bias, then that bias is built in.

We’re born with our biases. So what’s an investor to do?

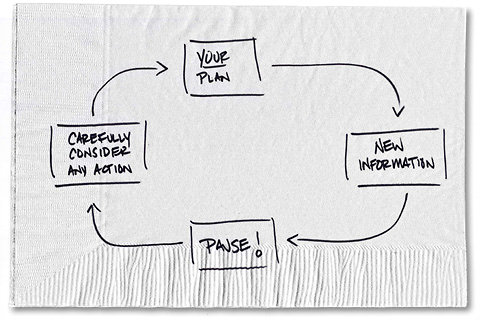

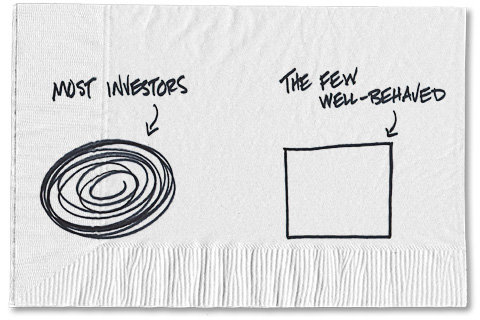

Since behavior plays such a huge role in investing — and as Dr. Kahneman notes, these biases are hard to avoid — you need a strategy to keep you on track. The best source for figuring all of this out is watching the people who do behave well. What do they do differently than the average investor?

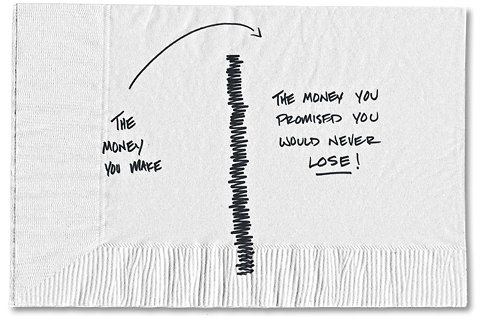

1) Separate decisions from emotion

I’ve often said that I’m great at making unemotional decisions when it’s another person’s money. But when it comes to my own money, it can be a struggle. Warren Buffett is a perfect example of this principle. Mr. Buffett has said over the years that he tries to be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful. That is essentially putting into practice the notion of “buying low and selling high.” And it means sticking with a plan even when it’s painful (for instance, when stocks suddenly jump or slump).

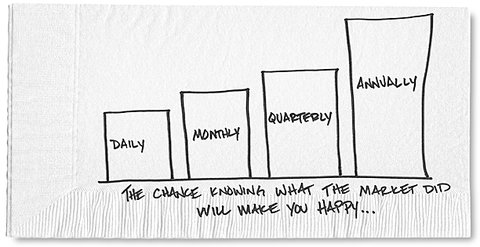

2) Doing nothing is the default choice

When I heard about the study that found soccer goalies could be more successful by doing nothing, I immediately understood why there would be resistance to the idea that not moving could block more goals. I suspect most of us have a bias toward action, especially if we think we’ll look stupid if we stand still. The best behaved investors understand that it’s in their best interest to do nothing most of the time, even though everyone else around them may be saying otherwise.

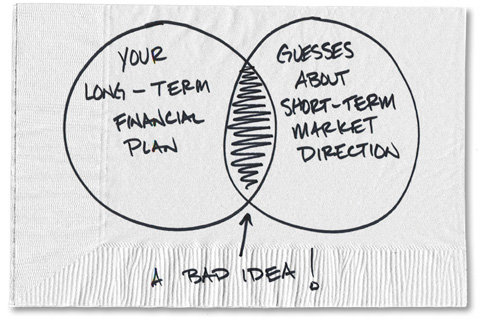

3) Understand that investing and entertainment are two different things

I’m the first to admit that reading and watching the so-called financial news can be interesting, even outright entertaining. But those who manage to behave seem to have adopted two approaches: watch it, but don’t act on it or ignore it completely. They’ve drawn a line between investing and entertainment. They may watch and read, but what they see doesn’t sway them from their plan.

Obviously, none of these three things are particularly complicated. So is something more going on? Is it a case of survivorship bias, where the people who appear to behave just haven’t made a mistake yet?

I doubt it. I think well-behaved investors are just better equipped than the average investor over the long haul. But they’ve also done something that the rest of us can do. They have acknowledged the connection between emotion and behavior.

There are no guarantees that we’ll avoid our biases in the future, or that we’ll avoid making mistakes. But simply recognizing that the land mine exists may get us out of some difficult situations or avoid them entirely. So take a look around you.

Do you know anyone who seems particularly well-behaved? How about someone who bought something like a low-cost index fund and then stayed put for 10, 15, even 20 years?

What have you noticed about them?

Maybe I’ve misjudged the situation, and perhaps it isn’t possible to behave over the long haul. Still, I’d like to think that we have enough examples from well-behaved investors to learn from. And that can help make the seemingly impossible become more probable for the rest of us.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/08/lessons-learned-from-well-behaved-investors/?partner=rss&emc=rss