Carl Richards

Carl Richards

Carl Richards is a certified financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at BAM Advisor Services. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published this year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

With less than a month to go until Election Day, it’s hard to miss all of the speeches about taxes. Tax rates, tax codes, tax deductions. So it’s easy to see why we’re so tempted to get really focused on our own personal tax situation and how to eke out a better result for ourselves.

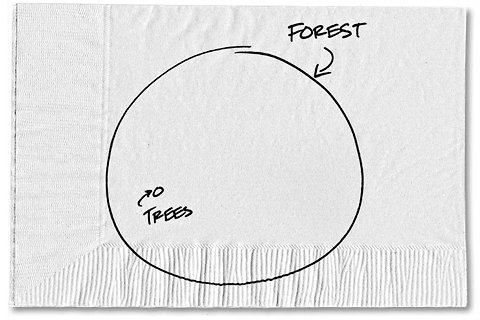

But you know the old saying that we shouldn’t miss the forest because we’re so focused on the trees? Well, it happens with our investment decisions and taxes on a regular basis.

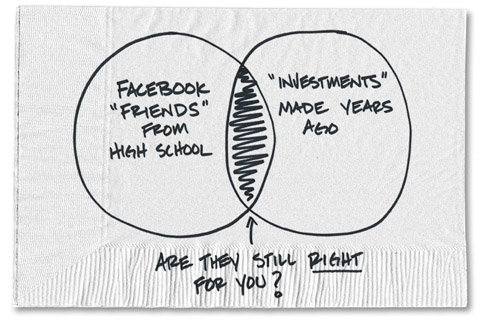

I had a recent conversation with some friends about a rental home they owned. They were evaluating their options for the property. Should they keep it? Remodel it? Sell it and look for an alternative investment?

As we walked through the details, it became clear to all of us that they have a great little investment in the context of their overall financial plan. Based on the price they paid years ago, the money they put into the house, the rental history and the income they collect, it appeared to be a much better investment than the alternatives they were considering, even when we accounted for the risk associated with rental properties.

But as soon as we came to that conclusion, they asked me this: “Why did our accountant tell us the opposite?”

Now, their accountant prefaced his advice with the disclosure that his job was to focus on taxes. Based on that perspective, his advice was to sell it because they currently qualified for a substantial tax savings on the capital gain that would not be available to them in the near future.

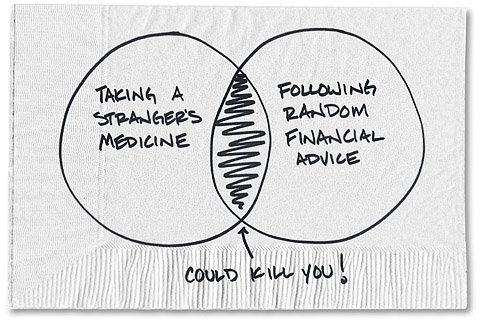

To be clear, the accountant didn’t give my friends bad advice. Instead he gave them advice based on one perspective, taxes. The reality is that smart, long-term financial decisions need to take more than one thing into consideration. But because taxes are associated with so much emotion (given how much people truly hate paying them), it’s incredibly easy to let taxes become our sole focus. And that can lead to bad decisions.

In this particular example, even when you included the tax savings, it still made sense to keep the property once we zoomed out and considered the decision in the context of their overall plan. In this instance, we were trying to avoid the trap of the tax tail wagging the investment dog.

Another situation where taxes can cloud our judgment comes in the form of spending more to deduct more. I’ve heard one of my doctor friends say that she’d been told to buy a larger home with a bigger mortgage so she could receive the greater interest deduction.

Now there may be other reasons to buy a bigger home, but spending another dollar in interest just so you can get something far less than that back in taxes just doesn’t make sense unless it’s part of some bigger plan.

Taxes and the way we feel about them can pull us into emotional quicksand. And when we make taxes our primary focus for financial decisions, it’s no wonder we get trapped into making decisions we may regret later. In the case of my friends, if they’d skipped over their initial assessment and made the decision to keep or sell the rental property based solely on the tax advice, they most likely would have regretted it.

Yes, we need to know the tax implications of our decisions, and getting good advice on the issue is helpful. But we need to be really careful to not let one perspective keep us from seeing the forest and making the wiser decision for our overall plan.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/08/when-the-tax-tail-wags-your-investment-dog/?partner=rss&emc=rss