Carl Richards

Carl Richards

Carl Richards is a certified financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at The BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published this year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

I used to ride my road bike a lot.

While I didn’t race very often, I did ride with a group of really competitive riders. And when you ride a bike competitively, especially when long climbs are involved, weight is a factor. The less you weigh, the faster you go. Needing all the help I could get, I got in the habit of stepping on the scale regularly, and that habit has stuck with me even though I ride less now than I did a few years ago.

As I’ve observed my interaction with the scale, I’ve noticed a curious tendency. I’m much more likely to weigh myself when I’ve been eating well, and I think I’m going to like the number I see. I’ve also noticed that I pretend the scale doesn’t exist after a late-night ice cream session. Sound familiar? Even the time of the weigh-in mattered. Based on a quick poll of my athlete friends, their preferred time for the daily weigh-in is after an early morning run and right before breakfast.

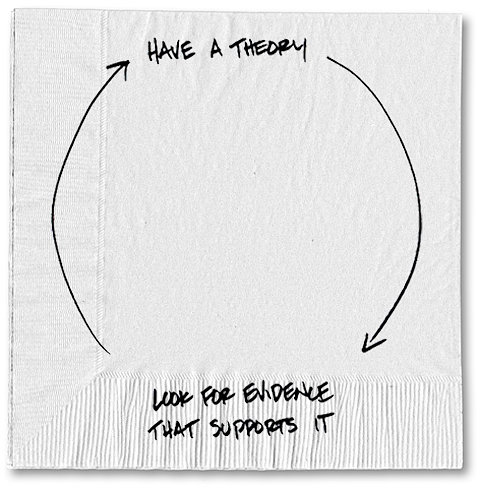

This tendency to look for information that supports the way we feel about something isn’t isolated to the scale. We do this all the time. In fact, academics even have a name for it: confirmation bias. It’s when we form an opinion, and then we systematically look for evidence to support that opinion while discarding anything that contradicts it.

The first place we go for feedback about what we believe is other people. And who do we ask first? That’s right, people we know who are already inclined to think the same way as we do. And friends don’t always tell one another the truth, even if they disagree. The result is a dangerous feedback loop that actually confirms our bias. It’s incredibly hard to avoid.

A great example of this bias is described in “Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work,” a new book by Chip and Dan Heath:

Smokers in the 1960s, back when the medical research on the harms of smoking was less clear, were more likely to express interest in reading an article with the headline “Smoking Does Not Lead to Lung Cancer” than one with the headline “Smoking Leads to Lung Cancer.” (To see how this could lead to bad decisions, imagine your boss staring at two research studies headlined “Data That Supports What You Think” and “Data That Contradicts What You Think.” Guess which one gets cited at the staff meeting.)

Confirmation bias is super tricky because it’s so easy to convince ourselves that we’re right. We’ve found evidence to support our decision and people who agree with us. The only solution that I see is to purposely expose yourself to views that don’t match yours.

For a great example, let’s look at politics. Let’s say you consider yourself a liberal. Chances are most of the people you hang out with are liberals, too. So the only way to avoid this confirmation feedback loop is to expose yourself to views that don’t match yours.

The hard part? You’ve got to do it with an open mind. As Stephen Covey, the self-help and business author, has said, “Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply.”

Your goal should be to understand. If you are just listening to judge, then you’re only building more confirmation into the system.

So take a deep breath and turn on Fox News or listen to Rush Limbaugh. Try, just try, to listen, to understand. See if you can get to the point where you can honestly say, “I understand the argument and can see why they feel that way.”

Of course, this may not change your views. But then again, it might. In fact, the possibility of changing your mind might be why this is almost impossible for most of us to do. Beyond politics, we face just as much risk of confirmation bias in investing.

Suppose you’ve watched the market race up during the last few months, and you think the market is close to its peak. Maybe, you think, it’s time to get out. I can guarantee you’ll be able to find evidence — probably enough to write a thesis — that supports your decision. But I’m just as sure that there’s plenty of evidence that says otherwise. And that’s the slippery slope of confirmation bias.

We’ll always be able to find something or someone that says, “Yes, you’re right.” But our goal should be to understand the opposite of what we believe, put it into context with what we think is true, and then see where we stand. Otherwise, what we “think” we know will someday be trumped by what we don’t.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/20/challenge-what-you-think-you-know/?partner=rss&emc=rss