Just when you thought it might be safe for the Fed to begin to think about taking its foot off the accelerator, along comes a jobs report that makes the employment picture look much less rosy than we had thought.

FLOYD NORRIS

Notions on high and low finance.

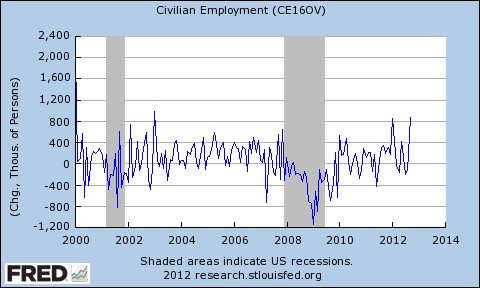

The most distressing part of the report came from the household survey. It found that 206,000 fewer people were working in March than during the previous month. That would make it the worst month in more than a year. (The more widely followed establishment survey found employment rose by a disappointing 88,000.)

The household survey also found the labor force participation rate – the proportion of people at least 16 years of age who were working or looking for work – fell to 63.3 percent, the lowest rate since 1979.

That fuels the narrative that the unemployment rate is coming down not because the economy is getting better, but because people are giving up looking for jobs. It raises the specter that the Washington follies are having a more serious impact than we had thought. Raising taxes on the least well-off working people – through the payroll tax increase that took effect at the beginning of the year – might have been a poor idea.

There are reasons to hope those fears are misplaced. The first is that the household survey is notoriously volatile. It covers 60,000 households, and the numbers can bounce around from month to month as different households are surveyed. (To minimize that, households stay in the survey for more than one month, but there are always changes.)

Over time, as the baby boom generation gets older, there is going to be some decline in the labor force participation rate as retired people represent a greater proportion of the group being counted. (You are treated the same whether you are 16 or 116.)

But month-to-month changes are not influenced much by that. Particularly notable in the latest report is that the participation rate for men 45 to 54 fell to 85.3 percent in March. That is only a dip of 0.1 percentage point from February, but it is the lowest level since the figure was first recorded in 1948. It is also two percentage points below the lowest figure during the recent recession.

The idea that a lot of men in their prime working years are becoming discouraged and giving up looking for work would be profoundly troubling. Let’s hope next month will produce evidence that what we have here stems more from sampling errors than from reality.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/05/the-shrinking-ranks-of-the-working/?partner=rss&emc=rss