The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported last week that women held 54,623,000 private sector jobs in June, an increase of 116,000 from the previous month and 63,000 more than they held in December 2007, when the previous high was set. The gap between records — 65 months — was the longest such period since the government began keeping track of the gender of job holders in 1964.

Men have been gaining jobs as well, but the 59,428,000 jobs they now hold is 1.8 million jobs below the previous high, reached in June 2007.

The relatively better performance of women does not appear to be the result of employer preference for female employees. In fact, the opposite may be true. In most industries, women’s share of the labor force is down from what it was when the recession began. But some professions with a predominantly female work force have done better than the economy as a whole.

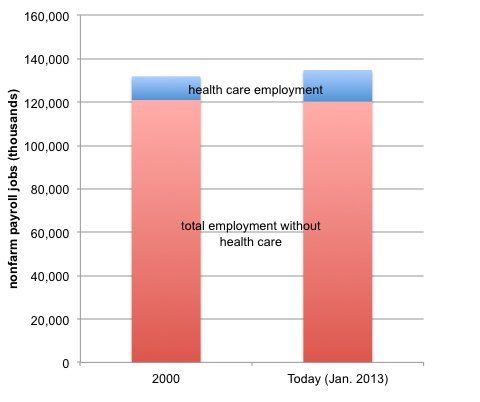

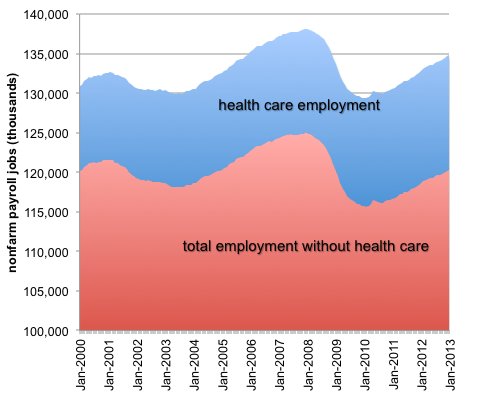

The best example of that is health care, where about 80 percent of the jobs are held by women. Employment in that industry continued to rise throughout the downturn.

The latest figures indicate that the number of men with jobs in the field is up 15.8 percent since January 2008, when overall employment peaked just as the Great Recession began, while female employment has risen by just 9.8 percent. But given the preponderance of women in health care jobs — about four out of every five workers in the field are women — those numbers translate into new jobs for more than twice as many women as men.

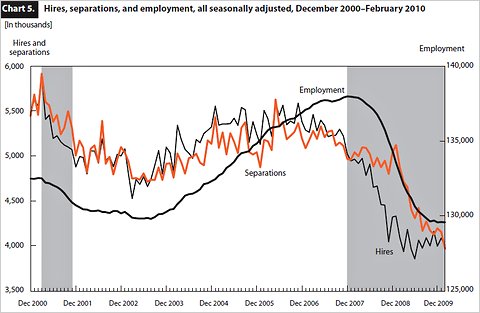

The charts accompanying this article compare job growth or shrinkage since January 2008. Women hold 0.1 percent more private sector jobs now than they did then, but male employment is still 2.8 percent below its level then.

The number of government jobs has been steadily shrinking, even as the economy recovers, and both male and female public sector employment is 2.4 percent below the levels of early 2008. There was a brief recovery in government employment in 2010 as temporary workers were hired to help conduct the census, but the underlying trend was negative.

The figures come from the government’s monthly survey of employers, which asks not only how many employees a company has but also how many of them are women. The figures are subject to revision, and there is no assurance that the slim female gain shown in the latest report will stand once the figures become final. For some industries, the figures are released with a month’s delay, and the charts for those industries reflect May employment levels.

In industries as disparate as manufacturing, information services and financial services, women and men lost jobs at about the same rate in the first year or two after the economy began to decline. But as the industries stabilized or began to recover, men were far more likely than women to find jobs. Since June 2009, significant numbers of jobs in all three industries have gone to men, while the ranks of women among jobholders continued to shrink in two of the fields, manufacturing and information services, and stabilize in the third, financial services.

In the category that includes restaurants and bars — in which women hold a small majority of the jobs — men and women lost jobs at roughly the same rate until the end of 2009. But since then, as employment increased, men have been more likely to find positions. For the entire period, male employment in such establishments is up more than 8 percent, while female employment has risen nearly 5 percent.

In the early months of the downturn, women came tantalizingly close to realizing a new milestone. In October 2009, women held 49.99 percent of all jobs, with private and public sectors combined. The difference in job totals was only 24,000 — 64,819,000 for men and 64,795,000 for women. But since then, as employment has risen, the female share has dipped to 49.37 percent, and men now have 1.7 million more jobs than women.

Floyd Norris comments on finance and the economy at nytimes.com/economix.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/13/business/economy/gender-gaps-appear-in-employment-recovery.html?partner=rss&emc=rss