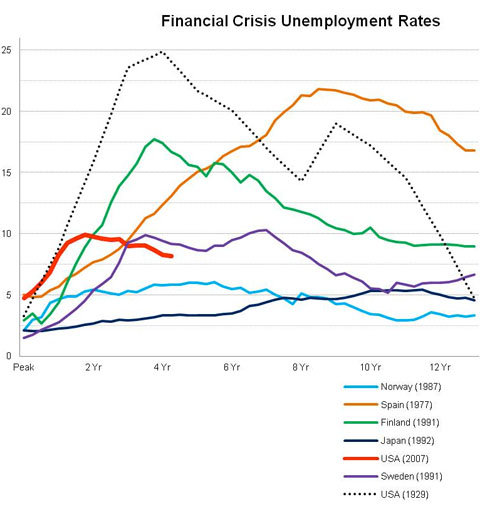

The job growth, almost exactly equal to the average monthly growth in the last two years, was enough to keep the unemployment rate steady at 7.8 percent, the Labor Department reported on Friday. But it was not enough to put a dent in the backlog of 12.2 million jobless workers, underscoring the challenge facing Washington politicians as they continue to wrestle over how to address the budget deficit.

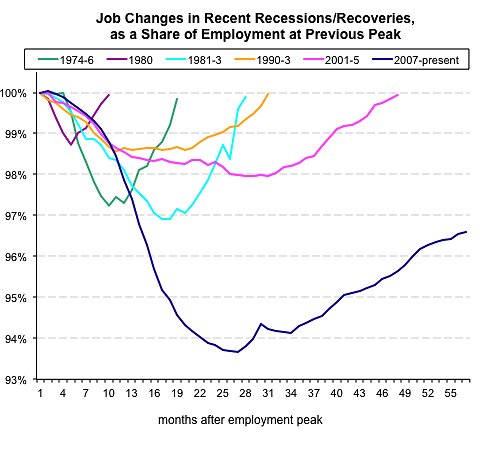

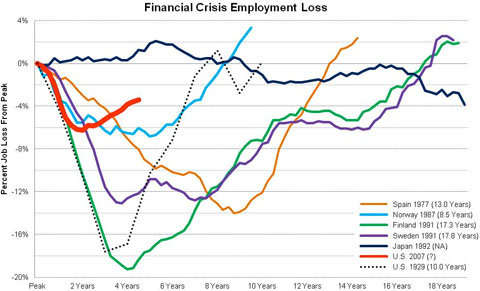

“Job creation might firm a little bit, but it’s still looking nothing like the typical recovery year we’ve had in deep recessions in the past,” said John Ryding, chief economist at RDQ Economics. “There’s nothing in the deal to do that,” he said, referring to Congress’s Jan. 1 compromise on taxes, “and nothing in this latest jobs report to suggest that. We’re a long way short of the 300,000 job growth that we need.”

If anything, the most visible debt-related options that policy makers are discussing could slow down economic and job growth, which, at its existing pace, would take seven years to reduce the unemployment rate to its prerecession level. The $110 billion in across-the-board federal spending cuts scheduled for March 1, for example, might provoke layoffs by local governments, military contractors and other companies that depend on federal funds.

A showdown over the debt ceiling expected in late February could also damage business confidence, as it did the last time Congress nearly allowed a default on the nation’s debts in August 2011.

“We may be seeing the calm before the storm right now,” said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomic Advisors, noting that a recent survey from the National Federation of Independent Business found that alarmingly few small companies planned to hire in the coming months. “Small businesses are wringing their hands in horror at what’s going on in Washington.”

A best case for the economy, many analysts say, would involve a swift and civil Congressional agreement that raised the debt ceiling immediately. It would also address the country’s long-term debt challenges, like Medicare costs, without sudden or draconian fiscal tightening this year.

Given the uncertainty over what Congress will do, estimates of the unemployment rate’s path this year vary wildly. The more optimistic forecasts for the end of 2013 predict that unemployment will fall to just above 7 percent, which would be considerably below its most recent peak of 10 percent in October 2009, but still higher than its prerecession level of 5 percent.

The job gains in December were driven by hiring in health care, food services, construction and manufacturing. The last two industries were probably helped by rebuilding after Hurricane Sandy.

Aside from the wild card of what happens in Washington, some encouraging trends in the economy — including the housing recovery, looser credit for small businesses, a rebound in China and pent-up demand for new automobiles — suggest that businesses have good reason to speed up hiring.

Congress’s last-minute deal to raise taxes this week will offset some of these sources of growth, since higher taxes trim how much money consumers have available each month.

President Obama’s proposals to spend more money on infrastructure projects and other measures intended to spur hiring are fiercely opposed by Republican deficit hawks. The fiscal compromise reached this week did include one modest form of stimulus, though: a one-year renewal of the federal government’s emergency unemployment benefits program. That program allows workers to continue receiving benefits for up to 73 weeks, depending on the unemployment rate in the state where they live, and stimulates economic activity because unemployment benefits are spent almost immediately.

The extension was a tremendous relief to the two million workers who would otherwise have lost their benefits this week.

“We woke up on Wednesday morning and saw the news and just said, ‘Thank God, thank God, thank God,’ and then went out and went food shopping because we knew we had money coming in,” said Gina Shadis, 56, of Newton, N.J.

Both she and her husband, Stephen, were laid off within the last 14 months from jobs they had held for more than a decade: she from a quality assurance manager position at an environmental testing lab, and he as foreman and senior master technician at an auto dealership. They are each receiving $548 a week in federal jobless benefits, or about a quarter of their pay at their most recent jobs.

“It has just been such a traumatic time,” Ms. Shadis said. “You wake up in the morning with shoulders tense and head aching because you didn’t sleep the night before from worrying.”

More than six million workers have exhausted their unemployment benefits since the recession began in December 2007, according to the National Employment Law Project, a labor advocacy group.

Millions of workers are sitting on the sidelines and so are not counted in the tally of unemployed. Some are merely waiting for the job market to improve, and others are trying to invest in new skills to appeal to employers who are already hiring.

“I have a few prospects who say they want me to work for them when I graduate,” said Jordan Douglas, a 24-year-old single mother in Pampa, Tex., who is enrolled in a special program that allows her to receive jobless benefits while attending school full time to become a registered nurse. She receives $792 in benefits every two weeks, a little less than half of what she earned in an administrative position at the nursing home that laid her off last year.

Ms. Douglas calculates that her federal jobless benefits will run out the very last week of nursing school.

“This had to have been a sign from God that I had to do this, since it all worked out so well,” she said.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/05/business/economy/us-economy-adds-155000-jobs-jobless-rate-is-7-8.html?partner=rss&emc=rss