The study, issued on Wednesday by two former Census Bureau officials, suggests why many people remain glum even though the economy is growing and unemployment has declined.

Although median annual household income rose to $52,100 in June, from its recent inflation-adjusted trough of $50,700 in August 2011, it remained $2,400 lower — a 4.4 percent decline — than in June 2009, when the recession ended. This drop, combined with the 1.8 percent decline that occurred during the recession, leaves median household income 6.1 percent — or $3,400 — below its level in December 2007, when the economic slump began.

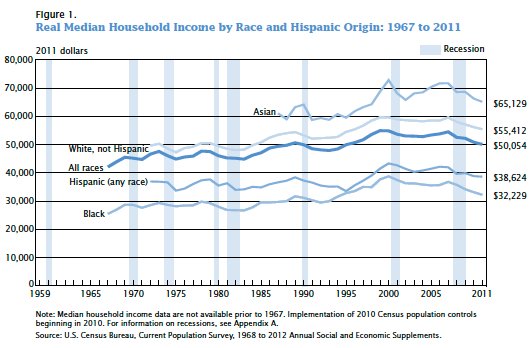

Since the end of the recession, the study said, household income has declined for all but a few population groups. Some of the largest percentage declines occurred for groups whose income was already well below the median, like African-Americans, Southerners, people who did not attend college, and households headed by people under age 25.

“Groups with low incomes tended to have steeper declines in income,” said Gordon W. Green Jr., who wrote the report with John F. Coder, a colleague at Sentier Research, which specializes in analyzing household economic data.

Households headed by people ages 65 to 74 were the only group in the study that experienced a statistically significant increase in post-recession income, helped perhaps by the decision of some older workers to remain in the work force or re-enter it.

The figures, adjusted for changes in the cost of living over time, include income before taxes and exclude capital gains. The number of households with income above the median is the same as the number below it.

The data offers a potential preview of the official Census Bureau statistics on income and poverty for 2012, scheduled to be released next month. The Sentier data is based on the Current Population Survey, a monthly government survey of about 50,000 households. The researchers used the same definition of income as the Census Bureau uses in its annual report on income and poverty. The two sets of estimates have shown broadly similar trends in recent years.

Because recessions rarely match up with calendar years, the annual census data often does not allow for precise comparisons with the start and end of downturns. The most recent downturn ended in June 2009, according to a panel of academic economists widely considered to the arbiter of the business cycle.

The economy has been growing since 2009, but more slowly and inconsistently than many Americans would like and many economists and policy makers had predicted. President Obama has made the economy’s condition his main focus this summer, promising new efforts to encourage economic growth, including a series of proposals on higher education that he is expected to announce Thursday. While taking credit for some improvement in the economy, he has acknowledged that many Americans have yet to see the benefits.

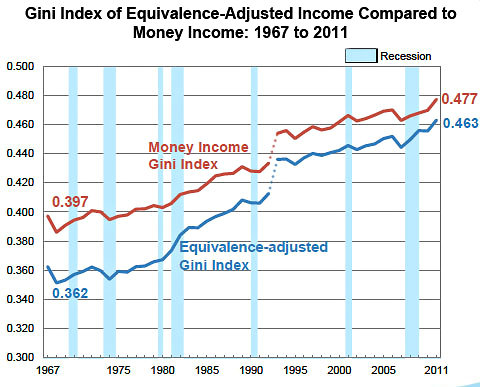

“We’ve got more work to do,” Mr. Obama said last month at Knox College in Galesburg, Ill. “Even though our businesses are creating new jobs and have broken record profits, nearly all the income gains of the past 10 years have continued to flow to the top 1 percent. The average C.E.O. has gotten a raise of nearly 40 percent since 2009. The average American earns less than he or she did in 1999.”

In the recession and its aftermath, many people went back to school, earning associate or bachelor’s degrees. Such credentials have helped, the new data shows, but they have been no guarantee against loss of income.

Households headed by people with only a high school diploma have seen their post-recession income decline by 9.3 percent, to $39,300 in June of this year, the report said. For households headed by people with an associate degree, median income declined by 8.6 percent in those four years, to $56,400. And among households headed by people with a bachelor’s degree or more, median income declined by 6.5 percent, to $84,700.

Since the end of the recession, the report said, income has declined by 3.6 percent for non-Hispanic white households, to $58,000, and by 4.5 percent for Hispanic households, to $41,000. Those changes were smaller than the 10.9 percent decline, to $33,500, for non-Hispanic black households, whose economic problems are likely to be a focus when Mr. Obama speaks next week on the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington.

Median income for households headed by people ages 65 to 74 increased by 5.1 percent, to $43,000, even though in many cases the head of the household was retired. By comparison, median income for households headed by people under age 25 fell 9.6 percent, to $31,300.

Median income declined by 4.5 percent for households headed by a person 25 to 34 years old, by 5.7 percent for those 35 to 44, by 2.5 percent for those 45 to 54, and by 7 percent for those 55 to 64. The report found no significant change for households headed by a person 75 or older.

Median income declined for households in three of four geographic regions, with the South showing the largest decline and the Midwest reporting no statistically significant change.

From June 2009 to June of this year, household income declined by 6.2 percent in the South, to $47,900; by 5.2 percent in the West, to $56,400; and by 3.9 percent in the Northeast, to $56,800.

By contrast, household income in the Midwest, $52,600, was not significantly different from what it was four years ago. Some parts of the Midwest have been helped by the natural-gas boom, while others have benefited from a modest manufacturing rebound in the last few years.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/22/us/politics/us-median-income-rises-but-is-still-6-below-its-2007-peak.html?partner=rss&emc=rss