Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

It has become customary to see our health care sector as a burden on society. In some ways it is. We have developed a complicated system of financing the sector – one guaranteed to put stress on the budgets of many households and governments at all levels.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Furthermore, we have structured the system so that prices for virtually any kind of health care in the United States are at least twice as high as prices for the same things in other countries. It is the main reason that health spending per capita in the United States is about double what most other nations spend. (Earlier this week, the Congressional Budget Office reported a sharp slowdown in the growth of health care costs, leaving budget experts trying to figure out whether the trend will last and how much the slower growth could help alleviate the country’s long-term fiscal problems.)

From a macroeconomic perspective, the health care sector has functioned for some time as the main economic locomotive pulling the economy along. In the last two decades, it has created more jobs on a net basis than any other sector.

Oddly, not much is made of the job-creating ability of the health care sector in political debate over health policy, in contrast to discussions of military spending, where employment always ranks high among the arguments against cuts. In October 2011, for example, Representative Buck McKeon of California, the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, made that point, among others, in a commentary in The Wall Street Journal, “Why Defense Cuts Don’t Make Sense”:

And on the economic front, if the super committee fails to reach an agreement, its automatic cuts would kill upwards of 800,000 active-duty, civilian and industrial American jobs. This would inflate our unemployment rate by a full percentage point, close shipyards and assembly lines, and damage the industrial base that our war fighters need to stay fully supplied and equipped.

Not surprisingly, in its “Defense Spending Cuts: The Impact on Economic Activity and Jobs,” the National Association of Manufacturers makes the same point.

For what it is worth, economists do not view “job creation” as an industry’s valuable output. Instead, when Industry A creates jobs and with them additional output, economists ask where the workers filling these jobs would have worked instead and whether the value of their output there would be smaller or larger than the output they produce in Industry A.

But health care has one additional feature I stumbled upon while writing a recent paper: from a macroeconomic perspective, it serves as an automatic stabilizer that offsets fluctuations in the growth of growth domestic product. Corporate and personal taxes and transfer payments such as unemployment benefits or additional enrollment in Medicaid are classic forms. They actually change countercyclically with changes in G.D.P., but health spending levels remain fairly stable as G.D.P. fluctuates.

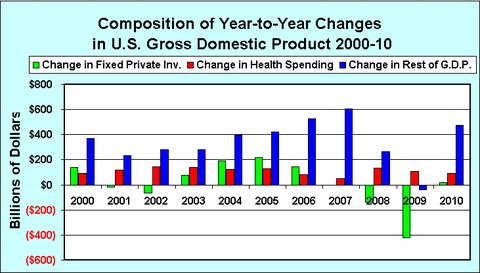

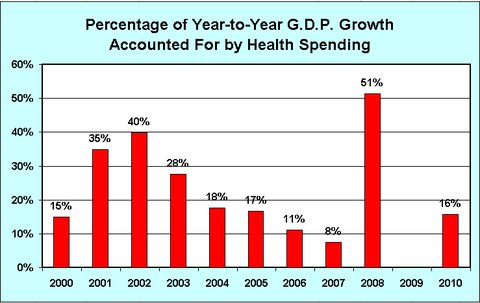

The chart below presents the year-to-year changes in total national health spending, in total private fixed investments and in the rest of the G.D.P. from 2000 to 2010. The second chart depicts the fraction of year-to-year changes in G.D.P. accounted for by year-to-year changes in national health spending, a component of G.D.P. In that chart, no column is shown for 2009, because from 2008 to 2009 private investment plummeted by $421 billion and total G.D.P. fell by $353 billion, while health spending rose by $107 billion.

The health spending data in these charts comes from Table 1 of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services publication “National Health Expenditures,” which provides national health spending data for the years plotted in the graph. The data on G.D.P. and fixed private investments come from the President’s Economic Report 2012, Tables B-1 and B-18.

It can be seen that total private investment fluctuates considerably over booms and busts. By contrast, health care spending remains fairly stable over time. It does tend to growth less rapidly in times of deep recessions, but it has not declined in the United States.

The next chart depicts the fraction of year-to-year changes in G.D.P. that is accounted for by year-to-year changes in national health spending, a component of G.D.P. In that chart, no column is shown for 2009, because from 2008 to 2009 private investment plummeted by $421 billion and total G.D.P. fell by $353 billion while health spending rose by $107 billion.

One must wonder what would have happened in the presidential elections of 2004 and 2012 if health care had not buoyed G.D.P. in the recession of 2000-1 and the recession that began in 2008.

One does not have to be a blind devotee of the Yale economist Ray Fair’s economic model of presidential elections, which relies on only a few variables to predict vote shares, to believe that one or both elections might have had different outcomes, even though both Presidents Bush and Obama inherited the recessions over which they presided.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/15/health-care-as-an-economic-stabilizer/?partner=rss&emc=rss