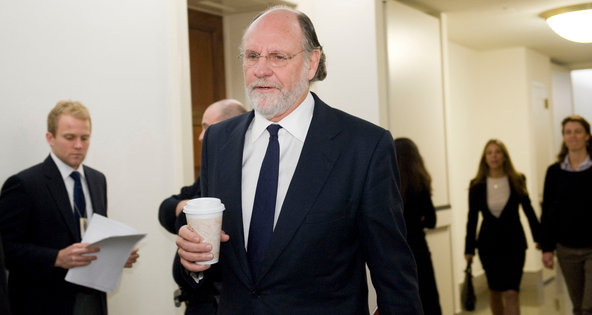

Michael Reynolds/European Pressphoto AgencyJon S. Corzine, MF Global’s former chief executive, at a House committee hearing this month into the collapse of the firm.

Michael Reynolds/European Pressphoto AgencyJon S. Corzine, MF Global’s former chief executive, at a House committee hearing this month into the collapse of the firm.

The congressional inquiry into MF Global continues, a hearing that will focus on the collapse of the commodities brokerage and the disappearance of an estimated $1.2 billion in customer money. Jon S. Corzine, the former leader of the brokerage who testified before a House panel last week, is appearing before the Senate Agriculture Committee on Tuesday. Lawmakers will also hear, for the first time, from two of Mr. Corzine’s former top deputies: Bradley Abelow, MF Global’s chief operating officer, and Henri J. Steenkamp, the firm’s chief financial officer.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=36c08a413cd405e82b9acbcd51bbd031

Updating…

Updating…