In a speech in 2004 to the General Counsel Roundtable, he said: “You’ve got to talk the talk; and you’ve got to walk the walk. Both are critical to maintaining a good tone at the top.” And he called for more accountability: “Hold all of your managers accountable for setting the right tone. That means disciplining or even firing them when they have failed to create a culture of compliance. Human nature being what it is, there will be those who break the rules. But if managers don’t do enough to prevent those violations, or let them go unaddressed for too long, then they should be held responsible — even in the absence of direct involvement in those violations.”

How times have changed.

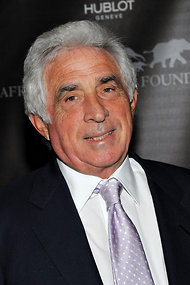

As general counsel of JPMorgan Chase Company, Mr. Cutler is now on the receiving end of the lectures, which this week came from George S. Canellos, a successor to Mr. Cutler and currently the co-chief of enforcement at the S.E.C. On Thursday, the S.E.C. and other regulators announced that JPMorgan had agreed to admit wrongdoing and pay nearly $1 billion in fines for its conduct in the “London Whale” matter, in which the bank’s chief investment office lost more than $6 billion and bank officials misled regulators about the losses. The S.E.C. faulted JPMorgan’s “egregious breakdowns in controls” and said that “senior management broke a cardinal rule of corporate management” by failing to alert the board to the full extent of the problem.

The S.E.C. didn’t name any of those senior managers, but made reference to the “chief executive,” who is Jamie Dimon. Mr. Cutler oversaw both the legal and compliance departments during those events. (Mr. Cutler no longer oversees compliance.)

And the London Whale affair isn’t JPMorgan’s only regulatory problem. The bank faces multiple other regulatory actions and investigations, ranging from manipulating energy markets, to mortgage-backed securities fraud, to failing to disclose suspicions about the Ponzi scheme operator Bernard Madoff, to conspiring to fix rates in the setting of the global benchmark interest rate informally known as Libor. As the allegations have mushroomed, JPMorgan has gone with almost dizzying speed from one of the world’s most admired banks to one tainted by scandal.

And all of this happened on Mr. Cutler’s watch. “You have to say, he didn’t run a tight enough ship,” said John C. Coffee Jr., a professor of law and expert in corporate governance at Columbia University. “It’s not just the London Whale episode. I wouldn’t call that the crime of the century. But taken with everything else, the energy manipulation, the mortgage fraud cases, the Libor rigging, it suggests that there was not enough investment in compliance and the general counsel was not proactive enough. He’s done a very good job at defending the firm but not enough at preventing it in the first place.”

A lawyer whose company was an S.E.C. target during Mr. Cutler’s tenure said this week, “I have to admit to a certain amount of schadenfreude,” adding: “At the time, he did a lot of grandstanding about lawyers being gatekeepers and the moral compass for the organization and how we should have prevented all this. He sounded great on the soapbox. Now I’ve been following JPMorgan and it’s pretty ironic.”

This lawyer was among the many I contacted who didn’t want to be named. I quickly realized that I was wasting my time trying to get people to offer unconflicted comments about Mr. Cutler or anyone else at the bank, since a) their firm represents JPMorgan; b) they represent someone for whom JPMorgan is paying the legal bills; or c) they’re trying to get into category a or b. James Cramer joked on CNBC’s “Mad Money” this week that JPMorgan should just buy the Manhattan law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton Garrison, famed for its high-stakes litigation practice.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/21/business/at-jpmorgan-trying-to-do-the-right-thing-isnt-enough.html?partner=rss&emc=rss