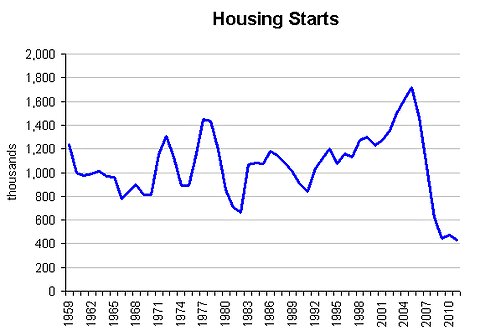

A reminder that there is a housing crash in progress:

Home builders started construction on just 428,600 single-family homes in 2011 and completed just 444,900 single-family homes, the Census Bureau reported Thursday. Both were the lowest totals since the bureau started keeping records in 1959. And the last few years have been much worse than any other stretch during that period.

Source: Census Bureau

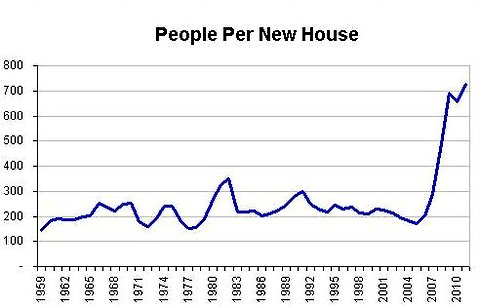

Source: Census Bureau

It is even more striking to adjust the level of construction for population growth. In 1982, the previous nadir, builders started construction on one new home for every 350 United States residents. In 2011, one new home was started for every 727 residents.

Source: Census Bureau

Source: Census Bureau

Including multifamily homes changes the picture somewhat. The 583,900 housing units completed in 2011 is stil the lowest number on record, but multifamily construction activity is starting to increase. Construction started on 606,900 units during the year, exceeding the totals in 2009 and 2010.

And there is growing sentiment among home builders and economists that the bottom has been reached and construction will increase in 2012. Builders are securing more permits, and the pace of housing starts rose in the fourth quarter.

“This is not another false dawn; it’s the real deal,” Ian Shepherdson, chief United States economist at High Frequency Economics, wrote in a note to clients this week.

Mortgage rates remain at record lows, more people are finding jobs, and Mr. Shepherdson sees signs that lenders are starting to loosen their purse strings. He points to a decline in average required down payments.

Add in the possibility of a huge settlement that could help some homeowners avoid foreclosure and allow lenders to foreclose on others more quickly, and there is reason to think the records set last year will endure.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=43e3e972843495ff7d465b63ee942b1d