Carl Richards

Carl Richards

We often talk about the problems that can come from being overconfident in making investment and financial planning decisions. What we don’t talk about as much is the high cost of being underconfident.

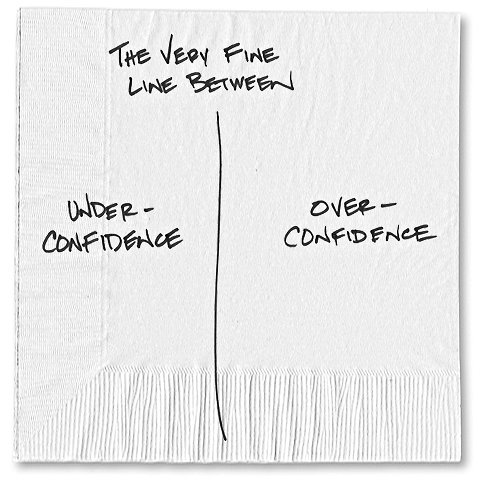

I often joke that you wouldn’t want an overconfident brain surgeon, but you don’t want an underconfident one either. The line between the two, though, can be fuzzy. So what does underconfidence look like?

1. I’m not worth that much.

The last time you applied for a job, how confident were you in negotiating your salary? Did you go in thinking I’ll be happy with whatever they offer or were you prepared to ask for more? Maybe you have lumpy income from freelance work. I know how hard it is to set a value on what you do. It’s more likely that we’ll go under than over. That underconfidence may end up costing you money. Humility is great, but it shouldn’t cost you an opportunity to earn what you’re worth.

2. I’m not sure I made the right investment decision.

Assuming that you’ve built a well-designed, diversified investment strategy based on a clear understanding of your current goals, you should feel confident. But even the best investment strategy will go through times of stress and second guessing. In fact, if we build our portfolios wisely — a diversified mix of low-cost index funds — by definition, parts of our portfolio are likely to be down when others are up.

We wouldn’t be human if we didn’t second-guess our decision when stocks go up and part of our portfolio is diversified in safe fixed-income investments. But not having the confidence to stick with that plan can lead us to make the big mistake: bailing on the plan.

3. I don’t like dealing with money.

We often spend a lot of time focused on our investments because we think that they’re the most important thing. But in reality, the choices we make every day with money often have a much bigger impact on our success over time — things like how much we save, how much we earn and how much we spend.

And while we can get help from people about how to be smarter savers, the hard work comes down to us. It can’t be outsourced. We need to have enough confidence to say no to certain things so we can say yes to the more important ones.

The only person who can do that is you. It takes a certain level of confidence to know when to say yes and when to say no, especially when it comes to sticking with a spending plan when all our friends don’t seem to have one.

At times, it may feel as if you’re walking a fine line between being too confident and not being confident enough. But here’s the thing: If you’ve taken the time to think things through, to have the conversations about what matters most and then make a plan, it’s an easier line to walk.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/05/the-costs-of-underconfidence/?partner=rss&emc=rss