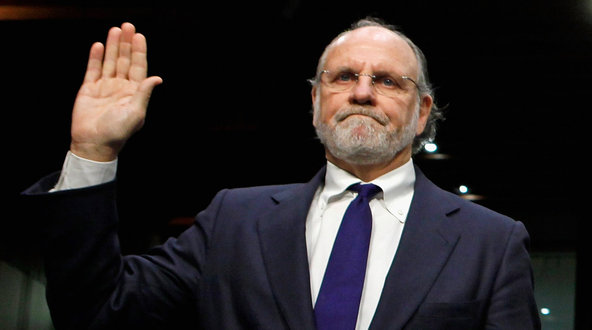

Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesJon S. Corzine, MF Global’s former chief executive, being sworn in at a Senate hearing on the firm’s demise. He will face more questions during a House hearing on Thursday.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesJon S. Corzine, MF Global’s former chief executive, being sworn in at a Senate hearing on the firm’s demise. He will face more questions during a House hearing on Thursday.

Congressional investigators are exploring whether regulators and feeble risk controls allowed MF Global to topple.

A House committee is expected to disclose on Thursday that MF Global, under Jon S. Corzine, stripped critical powers from its top executive in charge of controlling risk, according to a person briefed on the matter.

The move left the firm short-handed as it was grappling with the implications of its $6.3 billion position on European sovereign debt, a trade large enough to wipe out the firm if it soured.

Earlier this year, MF Global replaced its chief risk officer, Michael Roseman, after he repeatedly clashed with Mr. Corzine over the firm’s purchase of European sovereign debt. The new risk officer, Michael Stockman, took over the position in early 2011 with one major difference: unlike his predecessor, he was not allowed to weigh in on the broader implications the trades might have on the firm, including whether they might undermine investor confidence.

In the last week of October, as ratings agencies downgraded the firm and investors fled, MF Global’s liquidity dried up. The firm filed for bankruptcy on Oct. 31 after it was discovered that about $1 billion in customers’ money was missing.

The House Financial Services subcommittee will also focus its attention on the patchwork of 20 regulators and federal agencies charged with oversight of MF Global, according to a Congressional memo. It will afford the Republican-controlled committee an opportunity to take a swipe at Wall Street’s largely Democratic watchdogs.

In particular, the committee will examine the role of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which did not have direct regulatory oversight over MF Global.

The New York Fed this year designated MF Global a primary dealer, allowing it to trade directly with the bank in the buying and selling of United States government debt.

The chief legal counsel for the New York Fed is expected to say Thursday that as worries mounted over MF Global’s ability to stay afloat, the governmental institution issued the firm a margin call on Oct. 28 — demanding more money from the firm to continue trading with it.

The margin call raises the possibility that MF Global improperly transferred customer cash to meet the New York Fed’s demands. While the size of the margin call on the $950 million position was not specified in the counsel’s prepared testimony, the New York Fed used the cash to pay off $3 million in trading fees. The remainder of the money was turned over to the trustee overseeing the liquidation of MF Global’s brokerage unit.

Investigators on Wednesday would not say whether the money used to meet the margin call belonged to customers.

Lawmakers plan to question whether the firm deserved its primary dealer status to begin with. Such a distinction is not easily earned — just 21 financial firms worldwide have it. House panel members plan to point to MF Global’s weak earnings, low credit rating and lackluster business model as potential shortcomings that should have led the regulator to reject the firm’s bid.

In 2010, the New York Fed delayed the application because the firm faced federal enforcement actions over weak internal controls. It approved the application in February 2011.

Mr. Corzine has previously told lawmakers that the firm was better than some other primary dealers.

“We had adequate capital, and while, as I indicated in my written testimony, our historical earnings hadn’t been so good, they had gotten slightly better,” he told the House Agriculture Committee last week.

Pressed about his own personal involvement in securing the firm’s primary dealer title, Mr. Corzine, who commanded respect in Washington and Wall Street as a former Democratic senator from New Jersey and a former head of Goldman Sachs, noted that MF Global’s application began before he took over.

“I visited with people at the Federal Reserve, as I reported,” he said. But “never with either the president or chairman or any of the board of governors.”

Jonathan Ernst/ReutersWilliam Dudley, chief of the New York Fed, had frequent contact with Jon Corzine in the last days of MF Global.

Jonathan Ernst/ReutersWilliam Dudley, chief of the New York Fed, had frequent contact with Jon Corzine in the last days of MF Global.

He spoke briefly of his interaction with the New York institution, whose president, William Dudley, like Mr. Corzine, was also a former Goldman executive. While he did not engage with Mr. Dudley about the primary dealer designation, Mr. Corzine had repeated contact with him during the last days of MF Global, before it filed for bankruptcy. The contact included phone calls and e-mails, and were most likely about MF Global’s endangered status as a primary dealer, according to the person briefed on the matter.

The Federal Reserve, for its part, has said it was not responsible for the oversight of MF Global, and argued that the primary dealer designation of the firm was not meant to indicate the firm was infallible.

“We are not the regulators of MF Global — that’s done by the S.E.C, and C.F.T.C., so we do not have ongoing insight into developments within the company,” Ben S. Bernanke, the chairman of the Fed, said shortly after MF Global’s bankruptcy.

Thursday’s hearing will be Mr. Corzine’s third appearance before a Congressional panel examining the collapse of MF Global. Mr. Corzine, who was governor of New Jersey before joining the firm in 2010, has previously apologized for the firm’s collapse, but said he was “stunned” to learn that client money was missing.

A CME Group executive will also testify before the House Financial Services subcommittee, two days after suggesting that Mr. Corzine knew about the misuse of customer funds. The executive, Terrence Duffy, has not offered any clarity on the accusation since testifying before the Senate Agriculture Committee on Tuesday.

Whatever findings the panel uncovers in its hours of testimony Thursday, it is unlikely to determine the whereabouts of the missing customer cash. Two previous panels have yielded little insight on that front.

The money went missing, investigators say they believe, during the firm’s dying days in October. Some people close to the investigation have homed in on the firm’s primary bank, JPMorgan Chase, as a likely location for at least some of the funds.

After two Congressional hearings, frustration has bubbled over among customers, like farmers who remain in the dark about their missing money. “Making customers whole needs to remain the top priority,” said Debbie Stabenow, Democrat of Michigan, who leads the Senate agriculture committee.

The trustee liquidating the firm’s trading operations, James W. Giddens, has estimated that at least $1.2 billion in MF Global customer funds are missing.

On Wednesday, a federal bankruptcy judge in Manhattan approved a request by MF Global to continue using about $21.3 million of its cash on hand, allowing the firm to continue operating under Chapter 11.

The judge, Martin Glenn of the federal bankruptcy court in Manhattan, also ordered the trustee overseeing MF Global’s bankruptcy case, to begin a limited investigation into whether that cash included customer funds.

Judge Glenn’s decision to let MF Global continue using its cash on hand followed days of negotiations between Mr. Freeh and various objectors to the motion. In an opinion filed on Wednesday afternoon, the judge wrote that the need for use of the so-called cash collateral was “obvious”: It would pay for Mr. Freeh and the cadre of lawyers seeking to recover money for creditors.

Michael J. de la Merced and Susanne Craig contributed reporting.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=753fca7bef69f1e17101149de73cb733