Carl Richards is a certified financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at The BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published this year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

It’s tempting to think that the next new investment product is the solution to our behavioral problems. So it’s no surprise that I’m getting this question a lot: Do I need to invest in exchange-traded funds?

The fact that lots of people are confused about what E.T.F.’s are — they’re essentially index funds that trade on an exchange like stocks — and why investors might want them is no surprise. To add to the confusion, last week CNBC announced it was planning to design and offer its own E.T.F.’s. Seriously? Their announcement about the benefits of E.T.F.’s offers a great example of why people are so confused.

Here are some of the advantages CNBC cited:

1) E.T.F.’s offer diversification.

Sure they do, but this is nothing new or unique to exchange-traded funds. Traditional mutual funds were invented to offer diversification. Sure, you can now trade an E.T.F. that invests in only sugar. There’s also an E.T.F. for those “long-term investors” who want exposure to the inverse price of silver with a whole bunch of leverage. Is this what we’re talking about when we say E.T.F.’s offer diversification? In fact, there are more mutual funds to choose from than the number of stocks listed on the Nasdaq and New York Stock Exchange combined.

2) E.T.F.’s are low cost.

It’s true that some E.T.F.’s are an additional, low-cost alternative to index funds. Plus, you might be able to argue that the added competition from exchange-traded funds has driven down the cost of mutual funds. Remember, however, that there are also some very expensive E.T.F.’s and some extremely cheap mutual funds.

3) E.T.F.’s allow intraday trading.

Stop and think about that one for a minute. If you’re investing for the long term, why do you care if you can trade your investment every hour, minute and second of the day? The benefit of intraday trading only matters if you’re an active trader. And if you are, E.T.F.’s will just let you cut your own fingers off that much faster.

4) E.T.F.’s allow your adviser to place you in the right fund at the right time.

This is code for something that virtually no one can successfully do: time the market. Claiming that exchange-traded funds allow an adviser to add value by placing a client in the right fund at the right time is not only wrong, it’s dangerous. Any adviser who claims to be able to time the market is an adviser you should run from. Advisers are valuable if they can help you avoid the costly behavioral mistakes we all tend to make, not because they claim to be able to outperform the market.

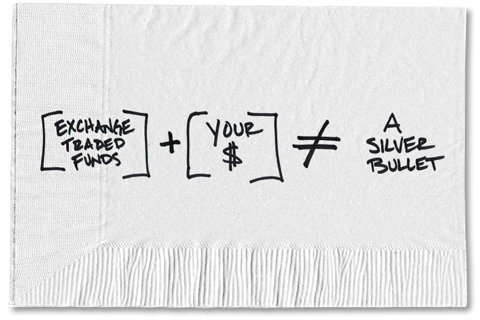

All the hype about E.T.F.’s is just throwing more fuel on the behavioral fire (see intraday trading, market timing). Ultimately, E.T.F.’s are just another tool that should be evaluated alongside all of the other tools available to help you reach your goals. To be clear, I’m not saying that all E.T.F.’s are bad. What I am saying is E.T.F.’s alone won’t solve our most vexing investing problem: our own behavior. In fact, they might just make it easier to behave badly.

For most long-term investors, exchange-traded funds don’t offer significantly different benefits over other low-cost funds. So my answer to the E.T.F. question is pretty simple: just because everyone else is doing it, doesn’t mean you should.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/15/why-e-t-f-s-wont-solve-our-behavioral-problems/?partner=rss&emc=rss