CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

As we’ve covered here many times before, there is an abundance of evidence showing that going to college is worth it. But that’s really only true if you go to college and then graduate, and the United States is doing a terrible job of helping enrolled college students complete their educations.

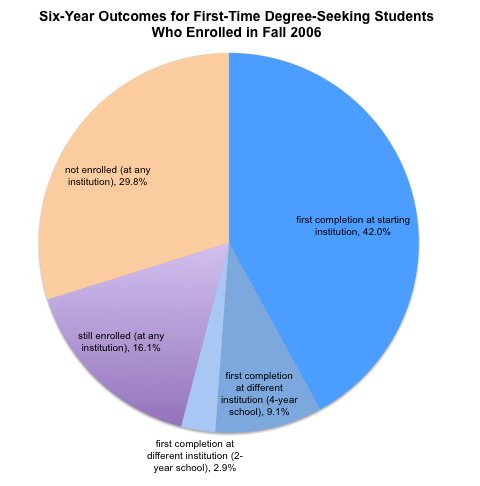

A new report from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center digs deeper into these graduation rates. It finds that of the 1.9 million students enrolled for the first time in all degree-granting institutions in fall 2006, just over half of them (54.1 percent) had graduated within six years. Another 16.1 percent were still enrolled in some sort of postsecondary program after six years, and 29.8 percent had dropped out altogether.

Source: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Source: National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

As you can see, many of the students who ultimately graduated did so at a different institution than the one where they had originally enrolled. Of the whole cohort of 2006 matriculants, 42 percent graduated where they had first enrolled, and another 9.1 percent graduated from a place to which they had transferred.

The graduation and transfer rates varied greatly by state, and by the type of institution in which the student first enrolled. In Minnesota, for example, 27 percent of students who enrolled at four-year public institutions graduated at a different school within six years. That was the highest share for any state in this metric.

A small share of students (3.2 percent) who started out at four-year schools ended up receiving their first degree or certificate instead from a two-year school, with rates above 5 percent in Minnesota, North Dakota and Wisconsin. On the other hand, 9.4 percent of all students who initially enrolled at a two-year public institution received their first degree at a four-year school.

The report also looked at the state-level completion rates for students who are “traditional” (that is, age 24 and younger) versus “nontraditional” or “adult” (over age 24).

Not surprisingly, in almost every state, traditional-age students starting at public four-year schools had higher completion rates than nontraditional-age students. The smallest gap was in Arizona (1 percentage point, 68.4 percent of traditional students graduating versus 67.6 percent of adult students) and the highest was in Vermont (42 percentage points, 74.3 percent versus 32.2 percent).

For more on this release, check out the Chronicle of Higher Education’s neat interactive visualization of the study.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/26/only-half-of-first-time-college-students-graduate-in-6-years/?partner=rss&emc=rss