Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

In a recent post, I examined aggregate national wealth from the Federal Reserve Board’s flow of funds statistics. They show that while national wealth is now approximately back to its precrisis level, the composition of it has changed. Much more is now held in the form of such financial assets as stocks and much less in nonfinancial forms such as housing. This is important, economically and distributionally, because the wealthy are much more likely to be invested in stocks and bonds, while the middle class has more of its wealth in home equity.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Several new studies cast further light on the composition and distribution of wealth, with implications for the ability of millions of Americans to retire and have an adequate retirement income.

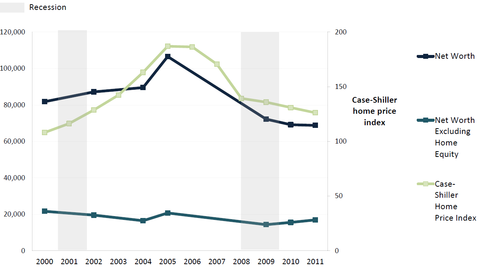

On March 21, the Census Bureau published data on median household wealth – the median is the exact middle of the distribution of wealth. It shows that between 2000 and 2005, median wealth increased significantly, to $106,585 from $81,821. It then fell to $68,828 in 2011. Thus, although the stock market is close to its prerecession peak and aggregate national wealth has largely been restored, the median family’s wealth is still considerably below its peak and needs to rise considerably just to get back to where it was in 2000.

The reason, of course, is that the housing market continues to lag. As Figure 1 illustrates, virtually all of the change in wealth since 2000 has been accounted for by the rise and fall of home equity, which closely tracks the price of homes.

United States Census Bureau, Survey of Income and Program Participation, 1996, 2001, 2004 and 2008 Panels Median net worth of households, in 2011 dollars. Median net worth is the sum of the market value of assets owned by every member of the household minus liabilities owed by household members; the Case-Shiller Home Price Index is a measure of home values that tracks home prices in 20 metropolitan regions.

United States Census Bureau, Survey of Income and Program Participation, 1996, 2001, 2004 and 2008 Panels Median net worth of households, in 2011 dollars. Median net worth is the sum of the market value of assets owned by every member of the household minus liabilities owed by household members; the Case-Shiller Home Price Index is a measure of home values that tracks home prices in 20 metropolitan regions.

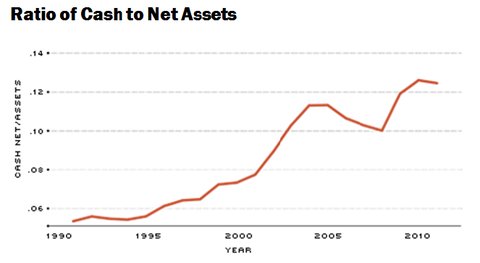

On the other hand, households have grown less dependent on housing wealth over time. In 1984, 41 percent of wealth was held in the form of home equity. By 2000, that percentage had fallen to 30 percent; in 2011 it was 25 percent.

A key reason for this change has been the switch from defined-benefit to defined-contribution pension plans. In the former, workers are promised a specific income at retirement, which the employer provides. The employer bears all the risk of market fluctuations.

Under a defined contribution scheme, such as a 401(k) plan, the worker and the employer jointly contribute to a tax-deductible and tax-deferred account from which the worker will finance retirement. Thus, to a certain extent, the growth of pension wealth is more apparent than real.

The worker always, in effect, owned the assets from which his pension was paid; he just never saw them or benefited when the stock market increased, nor did he suffer when the market fell. With a 401(k) account, the worker knows the present value of his retirement saving at the close of the market every day.

There are several big problems in this shift to defined-contribution pension plans. One is that workers don’t take advantage of them or fail to contribute the maximum contribution they are permitted to make. Another is that they fail to invest in stocks and instead put their money into certificates of deposit or other investments that tend to underperform stocks in the long run. Workers may also be unwise in choosing investment advisers and end up paying a lot in unnecessary fees that can be very costly to returns.

These mistakes are hardly surprising. Under defined-benefit plans, companies hired professional money managers to invest their pension funds. The average worker can hardly be expected to have the same level of expertise, nor do they have the time to investigate their options adequately. They also tend to be excessively risk-averse and invest too conservatively.

Now the first generation of workers who have virtually all their pension saving in defined-contribution plans is nearing retirement, and the news isn’t good. According to a March 19 report from the Employee Benefit Research Institute, only about half of workers nearing retirement have confidence that they have enough money saved for an adequate retirement.

Not surprisingly, retirement saving has taken a back seat to more pressing concerns – coping with unemployment, maintaining standards of living during an era of slow wage growth, putting children through increasingly expensive colleges and so on. People may also have simply underestimated how much money they needed to save in the first place.

This problem is much more severe for black Americans. According to a new study by the Institute on Assets and Social Policy at Brandeis University, black families have considerably less wealth than white families even when their incomes are comparable. Over a 25-year period, a $1 increase in income generated $5.19 in wealth for white families but just 69 cents for black Americans.

The study identified several possible explanations: years of homeownership, household income, spells of unemployment, education, and inheritances from parents. With regard to housing in particular, white families generally bought homes at an earlier age, thus building home equity longer; white families tended to get better mortgages, in part because they made larger down payments. Black Americans bought homes in poorer areas where there was less home price appreciation.

The wealth gap isn’t only racial, it’s generational. According to a March 15 study from the Urban Institute, young people today have considerably less wealth than their parents did at the same stage of life.

Factors include young people buying homes at a market peak and hence suffering disproportionately from the decline in home prices; they also put less money down, making it more likely that they have negative home equity. Younger workers have also tended to marry at a lower rate, have lower incomes than their parents, pay much higher costs for health insurance, and are more likely to graduate with college debts.

What’s really depressing about these studies is the lack of solutions and the likelihood that the problem will only get worse.

Republicans in Congress have pressed for years to convert Social Security, a classic defined-benefit pension, into a defined contribution plan, and also to convert Medicare into a voucher program. These changes would shift even more of the financial risk in retirement onto families that have yet to adapt to fundamental changes in employer pensions and the economy over the last 30 years. The future doesn’t look pretty.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/26/declining-wealth-rising-retirement-risk/?partner=rss&emc=rss