Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of the forthcoming book “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

Last week, I discussed the phenomenon of inflationphobia – an irrational fear of inflation that is constraining the Federal Reserve and holding back the economy. The roots of inflationphobia go back at least to the Great Depression, when inflationphobes made the same arguments year after year despite continuing deflation – a falling price level.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

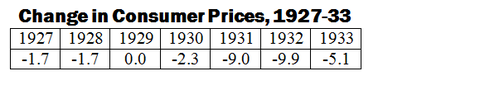

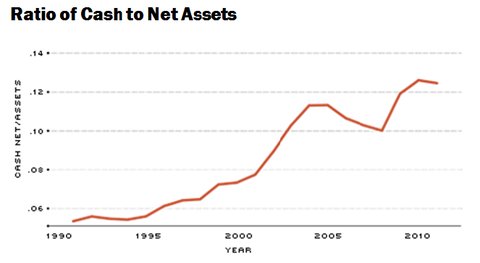

The defining characteristic of the Great Depression was deflation, which began in 1927, two years before the stock market crash. The following data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show the average change in the Consumer Price Index.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Between 1926 and 1933, the price level fell about 25 percent. This meant that any obligation fixed in dollars increased 25 percent in real terms. This was particularly important in two areas – wages and debts. If a worker managed to keep the same monetary wage between 1926 and 1933, she actually got an increase in pay of 25 percent in terms of what she could buy because the prices of things she consumed fell 25 percent.

Similarly, if one had a debt in 1926, the real burden of that debt and the debt service increased 25 percent between 1926 and 1933. This was especially important for farmers because the prices of agricultural produce fell very rapidly and the burden of their debts increased just as rapidly.

The great economist Irving Fisher thought that the increasing real burden of debt resulting from deflation was the core cause of the Great Depression.

Despite the falling price level year after year, there were inflationphobes even then, who saw signs of inflation, inevitably leading to German-style hyperinflation, everywhere. The leading inflationphobe was a writer named Henry Hazlitt. Although not trained as an economist, he had a strong interest in the subject and the rare skill to write about it clearly.

H.L. Mencken once said of Mr. Hazlitt that he was “one of the few economists in human history who could really write.” From 1934 to 1946, he was an editorial writer for The New York Times, writing a vast number of editorials and signed articles, mainly on economic issues.

In 1932, Mr. Hazlitt was still writing for The Nation magazine, where he was a strenuous supporter of the gold standard and a fierce critic of John Maynard Keynes, whom he viewed as nothing but a crude inflationist. Mr. Hazlitt thought the cure for deflation was for all workers to slash their wages, which would lower business costs and restore growth. Debtors would simply repudiate their debts and renegotiate them.

No doubt if workers had been willing to slash their wages 25 percent, and banks and bondholders had been willing to slash their interest and principal 25 percent, this would have gone a long way toward alleviating the negative economic effects of deflation. But absent a law requiring it – which the libertarian Mr. Hazlitt would have opposed – this process could only take place slowly, painfully and unevenly.

By contrast, simply reflating the price level back to its 1926 level was relatively easy. The Federal Reserve just had to increase the money supply sufficiently. By the 1960s, even the arch-conservative Milton Friedman said this was what the Fed should have done.

But in the early 1930s, the idea of reflation was controversial, mainly because bondholders enjoyed getting back 25 percent more than they had lent in real terms. Why should they give that up? That is why one of the strongest supporters of the gold standard and opponents of reflation was Benjamin M. Anderson Jr., chief economist of the Chase National Bank.

Irving Fisher and other economists argued in favor of reflation, even being joined by Winston Churchill, who had lately been chancellor of the Exchequer in England. But the most outspoken advocate of reflation was Mr. Keynes, who was quoted in The Wall Street Journal on March 2, 1932, as saying, “It is unthinkable that we can step straight from the financial crisis to relief of the industrial crisis without the cheap money phase intervening.”

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt became president and tried to stanch the deflation by suspending the gold standard and proposing legislation that would fix prices and prevent them from falling further. But these policies were ineffective because they did not get at the root of the problem, which was a fall in the money supply.

This resulted because there was no deposit insurance, so bank deposits literally disappeared when banks failed, and because the Fed refused to offset the resulting fall in the money supply through open-market monetary operations.

Mr. Fisher and some members of Congress kept pointing to the Fed, but to no avail. Responding to Republican attacks on reflation, Mr. Fisher said, there is “absolutely no escape from our present imminent danger except through reflation.”

They were opposed by Mr. Anderson and the New York banker James P. Warburg, who demanded restoration of the gold standard. In 1934, Mr. Warburg published a book detailing his criticism of reflation that was favorably reviewed in The Times by Mr. Hazlitt.

In a June 10, 1934, article for The Times, Keynes explained that monetary stimulus by itself was insufficient to stop deflation and that the

price-fixing instituted by the National Industrial Recovery Act was counterproductive, if well intentioned. He said government spending was essential to get money moving throughout the economy and recommended an increase of $400 million per month – close to $100 billion per month in today’s economy.

In an editorial probably written by Mr. Hazlitt, The Times rejected any resort to inflation no matter how much prices fell. “The one thing your inflationist cannot have too much of is inflation,” the editorial said. “Give him one dose and he becomes much more emphatic in his demands for another.”

In other words, it’s always a slippery slope – a little inflation today invariably leads to hyperinflation tomorrow. If economic stagnation and high unemployment result, it’s a small price to pay to avoid something worse, the inflationphobes always assert.

Next week I will have more to say about inflationphobia.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/16/inflationphobia-part-ii/?partner=rss&emc=rss