Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

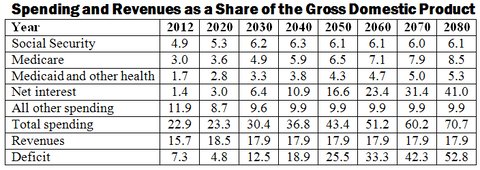

The Holy Grail for budget hawks is the “grand bargain” – some combination of tax increases and entitlement reforms that will get the deficit on a sustainable track, permanently. On paper, it always looks simple – relatively small adjustments to the growth path of revenues or big spending programs like Medicare or Social Security compound over time into big savings.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

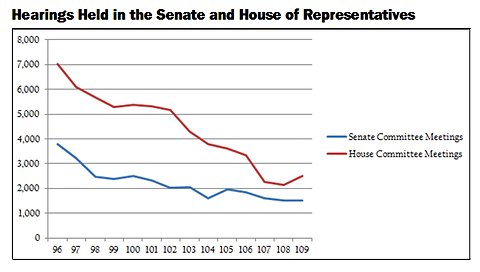

The problem, of course, is getting Congress to act, because of what economists call a time-inconsistency problem. The Congress that raises taxes and cuts benefits will suffer politically, while the benefits of lower deficits will accrue to future Congresses.

Historically, what has moved Congress to enact big deficit-reduction packages was the prospect of quick improvement in terms of inflation, growth and interest rates. Given that deficit reduction today is very unlikely to improve any of these in the near term, deficit hawks lack any real payoff from a grand bargain.

The two problems most likely to result from budget deficits are inflation and high interest rates. Many economists believe that deficits are inherently inflationary; others believe that they inevitably put pressure on the Federal Reserve to “monetize” the debt by, in effect, printing money to pay for it.

High interest rates are even more easily blamed on the deficit. As Floyd

Norris of The New York Times recently recounted, so-called bond vigilantes terrorized Wall Street in the early 1980s. Economists including Henry Kaufman of Salomon Brothers and Albert Wojnilower of First Boston regularly issued apocalyptic warnings of doom unless drastic action was taken on the deficit immediately.

It was often said that the Treasury’s borrowing was crowding out private borrowers from the bond market, because the federal government is not constrained by the amount of interest it is willing to pay. It will pay whatever the market demands to sell all the bonds it has to sell that day. Private borrowers will pull back their borrowing if rates get too costly.

Economists worried that if private companies lacked access to the bond market they would reduce investment in new plants and equipment, which ultimately reduced productivity and economic growth. High interest rates also raised the “hurdle” rate of return, snuffing out investments that in the past would have been profitable.

Some economists disagreed on the mechanism by which deficits affected interest rates. They pointed out that expected inflation automatically raises market interest rates. Generally speaking, a rise of 1 percent in the expected rate of inflation will raise long-term rates by 1 percent.

Those of a more liberal persuasion often contended that the Fed was forced to run a tighter monetary policy when faced with large deficits in order to offset their inflationary effect.

The precise mechanism didn’t matter much for policy purposes, because each perspective came back to the idea that deficits had to be reduced to improve the economy. Lower deficits would simultaneously reduce crowding out and inflationary expectations and give the Fed room to ease monetary policy – a virtual trifecta of payoffs.

It’s worth remembering just how severe the problem was. According to Mr. Norris, the interest rate on the Treasury’s 30-year bond peaked at 15.21 percent on Oct. 26, 1981. That is a rate almost incomprehensibly high given that Treasury bonds are assumed to have zero risk of default. The rate on the 30-year bond today is about 2.8 percent, about half its historical rate.

Even taking into account the fact that inflation was a serious problem in 1981 – the consumer price index rose 8.9 percent for the year – the “real” component of interest rates was very high. The real interest rate is the market rate minus the expected inflation rate.

With the benefit of hindsight, buying bonds in 1981 was the profit-making opportunity of a lifetime. Just imagine being able to get better than 15 percent a year on an investment for 30 years at zero risk.

Of course, at the time bonds were toxic, which is precisely why rates were so high. But as time went by, the deficit improved, inflation collapsed and the Fed eased. But it didn’t happen all at once; the process was slow and painful, involving many budget deals that were extremely difficult, politically.

Perhaps the most difficult was the 1990 deal, in which President George H.W. Bush courageously bucked his own party and agreed to a small increase in the top tax rate in order to get spending cuts and tough budget controls that deserve much of the credit for the budget surpluses of the late 1990s.

Mr. Bush’s own party basically turned its back on him, and it cemented for all time the now universally held Republican idea that taxes must never be increased at any time for any reason. Even those Republicans still sane enough to know this is nuts live in fear of a Tea Party challenger in the next primary, underwritten by the vast resources of the Club for Growth, which helped torpedo John Boehner’s “Plan B” effort at a “fiscal cliff” deal because it would raise the top tax rate on millionaires.

It is an article of faith to Grover Norquist, of tax pledge fame, that budget deals involving higher taxes are always bad for Republicans.

A new study from the European Central Bank confirms that significant deficit improvement is usually driven by rising interest rates. However, by the time budgetary action occurs the rising cost of interest on the debt tends to overwhelm the adjustment.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, none of the preconditions that historically are necessary for a significant budget deal are now present. Inflationary expectations continue to fall and real interest rates are very low. Hence, it is impossible for politicians to promise any benefit from large spending cuts or tax increases that would materially improve peoples’ lives. The benefits are purely abstract.

This suggests that we are a long way from meaningful legislative action on the deficit.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/01/when-the-deficit-will-be-fixed/?partner=rss&emc=rss