Book Chat

Talking with authors about their work.

Jeffrey Selingo, the former editor of The Chronicle of Higher Education and currently an editor at large there, is the author of a new book, “College (Un)Bound.” In it, he argues that the higher-education system is both vital to the American economy and “broken.” My exchange with him, edited slightly, follows.

You start your book by telling the story of a young woman named Samantha Dietz and describing the widespread phenomenon of enrolling in college without graduating. You write: “Only slightly more than 50 percent of American students who enter college leave with a bachelor’s degree. Among wealthy countries, only Italy ranks lower.” Why does the United States do a worse job of getting people through college than enrolling them in it?

Jay Premack Photography Jeffrey Selingo, author of “College (Un)Bound.”

Jay Premack Photography Jeffrey Selingo, author of “College (Un)Bound.”

College is one of the biggest financial investments we make in our lifetime, yet many families largely make their decision based on emotion. Prospective students start touring colleges in high school, well before they know how much a particular school might actually cost them. They are distracted by the bells and whistles on campus tours, fall in love with a campus and fail to ask the right questions. (Tools like collegerealitycheck.com and the Obama administration’s College Scorecard can help.)

So many students end up poorly matching to their campus. That’s why a third of students now transfer before earning a degree, and many unfortunately simply drop out.

At the same time, we have this fascination with the bachelor’s degree in the United States, and we think everyone needs to earn one at the same point in their lifetime, enrolling at 18 years old. The economy demands that more students have an education after high school, but not everyone is ready for college at 18. Many of them end up in college because we have few maturing alternatives after high school, whether it’s national service, apprenticeships or structured “gap year” experiences.

Finally, campus culture and money play a role. If you go to a college with a low graduation rate, your peers have an impact on your thinking: if no one else is graduating in four years, why should I? Others drop out because their financial situation changes while they are there and they can no longer afford it.

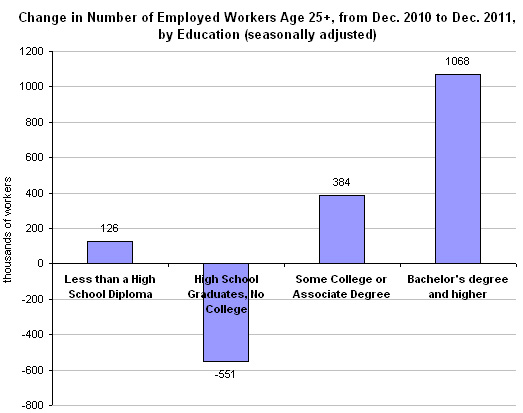

There is an economic reason we have a fascination with the bachelor’s degree, isn’t there? It brings a huge economic return. The jobless rate for four-year college grads is less than 4 percent, and the wage premium is very large — much larger than it once was. As you write, “By almost every measure, college graduates lead healthier and longer lives, have better working conditions, have healthier children who perform better in school, have more interest in art and reading, speak and write more clearly, have a greater acceptance of differences in people and are more civically active.”

How would you respond to the argument that everyone should aspire to a bachelor’s degree? Not everyone will make it. Many would need to start at a community college or with remedial work. But I can’t help but notice that most of the people arguing that “college isn’t for everyone” insist that their own kids go.

I’m not arguing that you shouldn’t aspire to a bachelor’s degree because, as you note, it does bring great economic returns. But why does it need to happen for everyone at 18?

Jacket design by Archie Ferguson; jacket art by Alessandroiryna/iStock photon

Jacket design by Archie Ferguson; jacket art by Alessandroiryna/iStock photon

For some, a two-year degree might be more appropriate at 18. And recent studies of wage data of college graduates in Virginia, Tennessee and a few other states show that the wage returns of technical two-year degrees are greater than many bachelor’s degrees in the first year after college.

Someone who isn’t ready for a four-year college at 18 and ends up dropping out is in some ways worse off than a high-school graduate who never went to college at all. Sure, college dropouts have some credits, but still no degree, and it’s likely that they have debt.

Let’s think of extending the period for a bachelor’s to be sure more students succeed in getting one. We don’t need alternatives to the bachelor’s degree, just more constructive detours on the pathway to college for those who are not ready at 18.

That’s a fascinating way of thinking about it: different paths, more than a different destination. (And whatever that study of Tennessee and Virginia shows about the first year after college, I have yet to see evidence that any alternative beats the long-term returns of a bachelor’s degree.)

Given how problematic it is for people to have college debt without a college degree — as many people unfortunately do — what do you think federal and state policy makers should do to change colleges with low graduation rates?

Well, the first thing federal and state policy makers can do is come up with a better way to measure graduation rates. The current rate counts only first-time students who enroll in the fall and complete degrees in “150 percent of normal time” – six years, for students seeking bachelor’s degrees. It doesn’t include students who transfer to other colleges and then graduate or those who transfer in and graduate. By one estimate, it excludes up to 50 percent of enrolled students.

A national student record database would allow policy makers to track students as they move among colleges. Once we have a better measure, then colleges that do well in actually graduating students should be rewarded, especially for those students who are not expected to complete college. For example, colleges that graduate Pell Grant recipients above the national average or students who are first in their family to go to college should get access to more federal aid for those students.

And all colleges need more skin in the student-loan game. Students are being saddled with higher amounts of debt, and the schools have little responsibility as they encourage more and more families to take on more debt. Right now, the only punishment is that colleges with high default rates are thrown out of the federal program. But that rarely happens. Colleges need to put some of their own dollars at risk if they are asking students and their parents to take on loans above certain amounts.

The last major section of your book is called “The Future.” So let me ask you to look ahead and predict one significant way in which a typical campus experience at a four-year college will be significantly different in 2023 than it is in 2013.

The biggest difference will be the injection of technology into the curriculum, with more courses taught in hybrid format, meaning a mix of face to face and online. That will allow for a more personalized experience for students so they can learn at their own pace and break the traditional idea of the academic calendar where everyone needs to start in September and end in May.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/31/how-to-cure-the-college-dropout-syndrome/?partner=rss&emc=rss