Republican leaders have already put at the center of their tax rewrite an idea borrowed from Europe and other countries: Replace the system of taxing the worldwide profits of a domestic corporation with one that taxes only profits earned within its own territory.

“If we don’t move to a more modern system, we may lose the ability to gain that revenue,” Mr. Camp warned.

Multinationals will inevitably shop around for low rates. Americans and foreign companies have all played the same games, shifting patents and copyrights, profits and royalties to places with no or low corporate tax rates, like the Cayman Islands and Bermuda. (The I.R.S. itself went after Amazon over assets it transferred to a Luxembourg unit, but Amazon ultimately prevailed.)

Efforts to cooperate have not always been successful, but there are signs that coordination can help. The Europeans’ effort is gradually shutting down the most notorious tax dodges that route corporate cash through Ireland and Luxembourg, said Michael J. Graetz, a professor and tax specialist at Columbia Law School.

“Those are like dinosaurs,” he said. “They’re moving towards extinction.”

And a new rule adopted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, requiring multinationals to report their income and tax bill in each country, will make it easier for the more than 60 governments that have signed on to monitor how much is actually collected.

So far, the team of Trump administration officials and lawmakers who drew up the latest framework for rewriting the tax code has released mostly general principles.

Now the I.R.S. taxes the worldwide profits of American corporations, but the tax kicks in only after that income is repatriated to the United States. As a result, American multinationals simply don’t bring much of it home. Republicans have made clear they intend to switch to taxing only profits earned within the United States, what’s known as a territorial system.

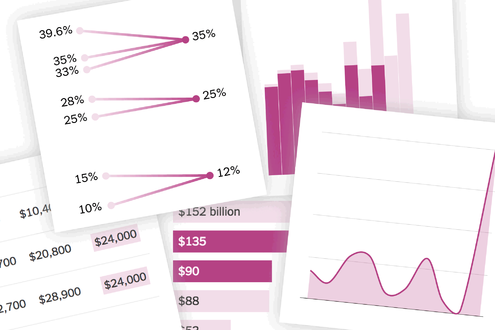

Graphic

Six Charts That Help Explain the Republican Tax Plan

The proposal lowers rates for individuals and corporations but leaves key elements up to Congress.

The $2.6 trillion in foreign profits that corporations already parked overseas in order to escape paying the I.R.S. would be required to be repatriated — although taxed at a steep discount. And there are promises to prevent the tax base from shrinking, and discourage businesses from putting more operations and earnings overseas. At the same time, the official corporate rate would be slashed to 20 percent, from 35 percent, to make American companies more competitive with their foreign rivals.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

But this frame still lacks a picture, missing the details of how to accomplish those ambitious if sometimes conflicting goals.

Without tough safeguards, for example, the shift away from a worldwide system could end up curbing rather than promoting investment at home as American companies move even more operations overseas to avoid paying any United States taxes.

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

To some experts, like Kimberly Clausing, an economist at Reed College, the only way to prevent American companies from exploiting loopholes in a new territorial regime is with a minimum tax. If a company’s tax rate fell below the floor in, say, Bermuda, it would have to pay the difference to the I.R.S.

Other experts, though, suggest borrowing another idea to broaden the tax base from foreign tax regulators — like more aggressive efforts to tax foreign multinationals.

As the Amazon and Apple cases show, “the politics in Europe are to tax somebody else’s multinationals, particularly ours,” said Mr. Graetz of Columbia.

“All of these other countries are basically trying to beef up and protect their tax base by ensuring foreign multinationals pay tax on income earned in their country,” he added, “and not on income earned by their own domestic multinationals.”

This is a different tack from the one taken in the United States, where tax dodges by homegrown billion-dollar corporations have been criticized for increasing the tax burden on companies that can’t shield assets.

The complaint that the American tax code favors foreign multinationals over domestic ones did, however, arouse interest last week at Senate hearings on a tax overhaul.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“The United States corporate and international tax rules are an anticompetitive mess,” said Itai Grinberg, a law professor at Georgetown University. And one of their most senseless features, he added, is the tax advantage that permits foreign-owned corporations to artificially strip out their earnings in the United States.

Both he and Bret Wells, a law professor at the University of Houston, testified that foreign and American companies should be treated the same way.

Leveling the playing field does not necessarily have to wait for a rewritten tax code. Adam Looney, a former deputy assistant secretary for tax analysis at the Treasury Department, said the Trump administration could take a step now. He urged the president to reverse a decision to delay an Obama-era regulation to limit foreign companies’ tax advantages and prevent them from transferring out their earnings.

“Without the regulations, American-owned businesses will be worse off,” while foreign multinationals avoid about $7.4 billion in United States taxes, Mr. Looney wrote this week in a policy brief for the nonpartisan Brookings Institution.

The delay, he said, means that the United States is, in effect, paying “foreign investors to take over our companies with our own tax dollars.”

Continue reading the main story

Article source: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/13/business/economy/corporate-tax.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.