Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

Steven Brill’s exposé on hospital pricing in Time magazine predictably provoked from the American Hospital Association a statement seeking to correct the impression left by Mr. Brill that the United States hospital industry is hugely profitable.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

In this regard, the association can cite not only its own regularly published data, but also data from the independent and authoritative Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, or Medpac, established by Congress to advise it on paying the providers of health care for treating Medicare patients.

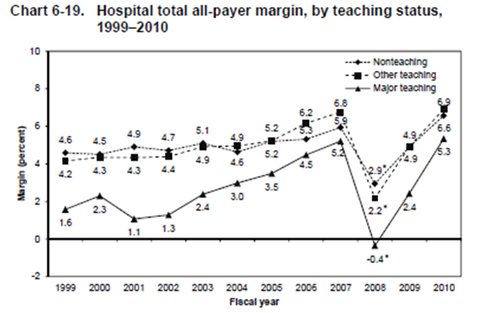

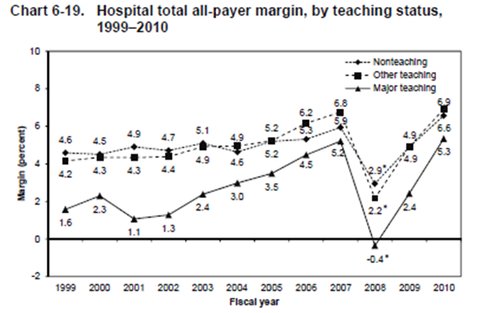

As shown by Chart 6-19 of Medpac’s report from June 2012, “Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program,” the average profit margin (defined as net profit divided by total revenue) for the hospital industry over all is not extraordinarily high, although for a largely nonprofit sector I would rate it more than adequate.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission

But in each year there is a large variance about that year’s average shown in Chart 6-19, with about 25 to 30 percent of hospitals reportedly operating in the red and many others earning margins below the averages.

The hospital association also correctly points out that under the pervasive price discrimination that is the hallmark of American health care, the profit margin a hospital earns is the product of a complicated financial juggling act among its mix of payers.

Payers with market muscle — for example, the federal Medicare and state Medicaid programs — can get away with paying prices below what it costs to treat patients (see, for example, Figure 3-5 and Table 3-4 in Chapter 3 of Medpac’s March 2012 report).

With few exceptions, private insurers tend to be relatively weak when bargaining with hospitals, so that hospitals can extract from them prices substantially in excess of the full cost of treating privately insured patients, with profit margins sometimes in excess of 20 percent.

Finally, uninsured patients — also called “self-pay” patients — have effectively no market power at all vis-à-vis hospitals, especially when they are seriously ill and in acute need of care. Therefore, in principle, they can be charged the highly inflated list prices in the hospitals’ chargemasters, an industry term for the large list of all charges for services and materials. These prices tend to be more than twice as high as those paid by private insurers.

To be sure, if uninsured patients are poor in income and assets, they usually are granted steep discounts off the list prices in the chargemaster. On the other hand, if uninsured patients are suspected of having good incomes and assets, then some hospitals bill them the full list prices in the chargemaster and hound them for these prices, often through bill collectors and even the courts.

It is noteworthy that in its critique of Mr. Brill’s work, the association statement is completely silent on this central issue of his report. A fair question one may ask leaders of the industry is this:

Even if one grants that American hospitals must juggle their financing in the midst of a sea of price discrimination, should uninsured, sick, middle-class Americans serve as the proper tax base from which to recoup the negative margins imposed on them by some payers, notably by public payers?

My answer is “No,” and I am proud to say that when luck put in my way an opportunity to act on that view, I did.

In the fall of 2007, Gov. Jon Corzine of New Jersey appointed me as chairman of his New Jersey Commission on Rationalizing Health Care Resources. On a ride to the airport at that time I learned that the driver and his family did not have health insurance. The driver’s 3-year-old boy had had pus coming out of a swollen eye the week before, and the bill for one test and the prescription of a cream at the emergency room of the local hospital came to more than $1,000.

By circuitous routes I managed to get that bill reduced to $80; but I did not leave it at that. As chairman of the commission, I put hospital pricing for the uninsured on the commission’s agenda.

After some deliberation, the commission recommended initially that the New Jersey government limit the maximum prices that hospitals can charge an uninsured state resident to what private insurers pay for the services in question. But because the price of any given service paid hospitals or doctors by a private insurer in New Jersey can vary by a factor of three or more across the state (see Chapter 6 of the commission’s final report), the commission eventually recommended as a more practical approach to peg the maximum allowable prices charged uninsured state residents to what Medicare pays (see Chapter 11 of the report).

Five months after the commission filed its final report, Governor Corzine introduced and New Jersey’s State Assembly passed Assembly Bill No. 2609. It limits the maximum allowable price that can be charged to uninsured New Jersey residents with incomes up to 500 percent of the federal poverty level to what Medicare pays plus 15 percent, terms the governor’s office had negotiated with New Jersey’s hospital industry.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the New Jersey hospital industry was cross at me and the commission for our role in the passage of Assembly Bill 2609. The commission took the view that it helped protect the industry’s image from some of its members’ worst instincts.

In that spirit, I invite the American Hospital Association to join me in urging federal lawmakers to pass a similar law for the nation. Evidently the mere guidelines on hospital pricing that the association published in 2004 have not been enough.

Indeed, in 2009 I had urged the designers of the Affordable Care Act to include such a provision in their bill — alas, to no avail. Courage to impose it on the industry had long been depleted.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/15/what-hospitals-charge-the-uninsured/?partner=rss&emc=rss