Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

Two themes run through the comments on previous blog posts that touched on the payment of the providers of health care. The first is that American doctors are paid too much. The second is that they are paid too little.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Could both propositions be right? Let us explore the issue by looking at some numbers.

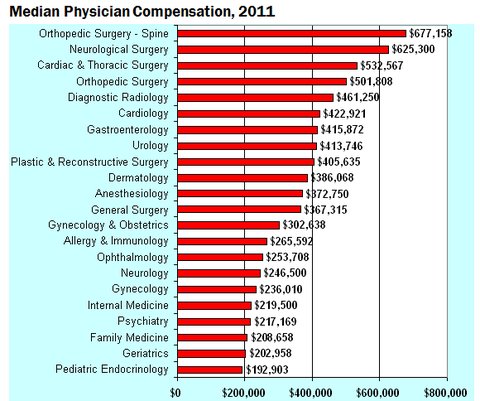

Figure 1, below, presents data on the median compensation reported by the American Medical Group Association for 2011. (The report shows data for many more specialties than can be shown in the chart.)

American Medical Group Association

American Medical Group Association

The American Medical Group Association is the national association of more than 130,000 doctors practicing in large medical specialty groups. Its data are very close to the median compensation data for doctors reported by the professional group-practice administrations represented by the national Medical Group Management Association.

As is regularly reported by the trade journal Modern Healthcare, data on median or average doctors compensation can vary significantly, depending on who does the survey, the sample they survey and the response rates they achieve (you can see this by clicking on the chart to the right of the headline on this page). I personally view the American Group Medical Association and the Medical Group Management Group data as the most reliable.

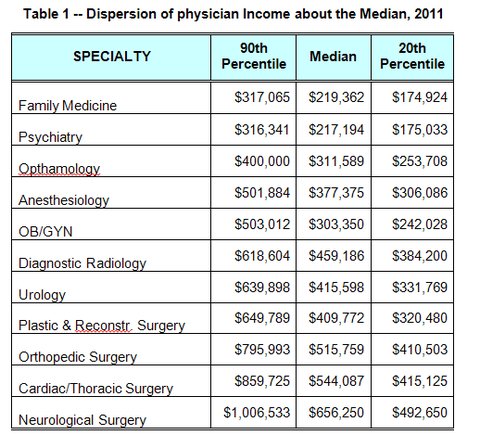

As we saw in Figure 1, the median compensation of doctors varies considerably among medical specialties in any given year. There is also a wide dispersion of compensation figures about the median for any given specialty, as is shown in Table 1. These data came from the previously cited American Medical Group Association survey.

American Medical Group Association

American Medical Group Association

The dispersion of doctor incomes is apt to be even wider if one includes not only physicians practicing in large medical groups but all practicing doctors.

Depending on their specialty, age, gender, whether they practice individually, in small groups or large groups and, most importantly, where they practice, a good many American doctors – especially primary-care physicians — probably do struggle to meet payroll, other practice costs and malpractice premiums and still have enough net income to support a family. This is especially so because as self-employed business professionals they do not get the fringe benefits available in formal employment in larger firms, and a good number of them have to repay principal and interest on educational debt that now averages $150,000 or so by the time residency training is over.

Over the last decade, the net incomes especially of primary-care doctors have hardly grown at all and even declined somewhat in inflation-adjusted dollars.

On the other hand, we read in the press that medical professionals are well represented in the top 1 percent of income earners in the United States. The ABA Journal of the American Bar Association reports that doctors outrank lawyers in that lofty cohort.

It should be noted, however, that one’s income does not have to be astronomical to rank among the top 1 percent of earners. A report on Bankrate.com noted that according to a model run by the Tax Policy Center and the Urban Institute, an income above $533,000 put one into the top 1 percent of earners in 2011.

So, what is one to make of these data on doctor incomes?

Are American doctors overpaid, as is sometimes argued, often with reference to physician incomes in other countries?

Or are American doctors underpaid, as about half of the physicians seem to think?

On this question, one can entertain several theories.

Standard economic theory suggests that over all, American doctors are overpaid, although perhaps not the primary-care specialties. This position leans on the fact that at existing incomes there is still considerable excess demand for places in medical schools among bright American youngsters – not to mention a huge pool of highly qualified foreign applicants. This suggests that the lamented doctor shortage in the United States is the result of an artificially constrained supply of medical school places and residency slots, which serves to inflate physician incomes above what they would be in a better functioning market without supply constraints.

As noted earlier, the idea that American doctors seem overpaid is often supported also with reference to what physicians in other countries are paid. Dana Goldman, an economist at the University of Southern California, for example, was quoted to that effect in an article in The New York Times.

My own view is that if one wants to go down that line of argument, the relevant comparison should not be doctors in other countries, but the incomes earned in the United States by members of the talent pool from which American physicians are recruited, a group that includes many who end up in the superbly well-remunerated financial markets, where they are well paid almost independently of their actual net contribution to society.

This position draws on the comparable-worth theory of compensation.

One can cite work by Christopher Conover of Duke University, who has estimated that the rate of return on the investment in human capital (i.e., education and training) to become a doctor is attractive – especially for the higher-paying medical specialties – but it is not as high as the rate earned on human-capital investments for other professions.

That finding, however, does not speak directly to the issue whether on average American physicians are over- or underpaid.

When in doubt, it may be wise to turn to the father of modern economics, Adam Smith. In “The Wealth of Nations” (published in 1776) he opined in Chapter 10:

We trust our health to the physician; our fortune and sometimes our life and reputation to the lawyer and attorney. Such confidence could not safely be reposed in people of a very mean or low condition. Their reward must be such, therefore, as may give them that rank in the society which so important a trust requires. The long time and the great expense which must be laid out in their education, when combined with this circumstance, necessarily enhance still further the price of their labor.

So when it came to contemplating the payment of doctors, Smith seems to have checked in his favored demand-and-supply framework at the door and slouched toward the medieval doctrine of just price. In my weaker moment, I slouch that way, too, as, I suspect, do many other economists, although my sentiment in this regard stops short of “lawyers and attorneys.”

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/24/debating-doctors-compensation/?partner=rss&emc=rss