Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

On Sunday, Catherine Rampell of The New York Times reported on the economic difficulties of those in their 50s and early 60s suffering from high unemployment and decimation of their retirement savings by the recession. Many will be forced to take Social Security benefits as soon as they turn age 62. Unfortunately, they may be risking unnecessary poverty in old age as a consequence.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

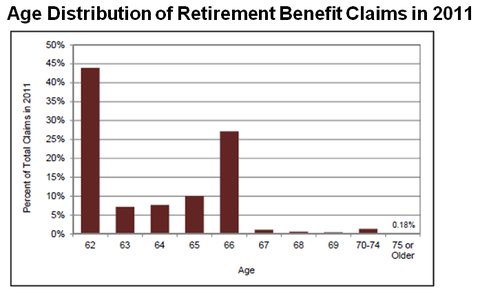

In 2011, 59 percent of those claiming Social Security for the first time were between the ages of 62 and 64, as shown in this figure from a recent Congressional Research Service report.

Social Security Administration, 2012 Annual Statistical Supplement

Social Security Administration, 2012 Annual Statistical Supplement

Historically, the normal retirement age has been 65, but life expectancy has risen over time. In 1940, a man age 65 could expect to live an additional 12.7 years, a woman 14.7 years. Longevity for men at age 65 increased to 17.6 years by 2009 and for women to 20.3 years, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (see Table 22).

Despite rising longevity, Congress created an option for early retirement at age 62 in 1961. It doesn’t appear that a great deal of thought was given to the long-term consequences of the decision. Contemporary reports say Congress was primarily concerned about unemployment among those approaching age 65 and viewed early retirement as a short-run stimulus measure.

According to C. Eugene Steuerle of the Urban Institute, creation of early retirement for Social Security had the unfortunate effect of changing workers’ expectations about the appropriate age at which to cease working. This has reduced lifetime productivity, taxes and retirement savings because workers spent fewer total years working.

Yet according to the 1962 Social Security Trustees report (see Page 6), the budgetary cost of allowing people to retire at age 62 was zero.

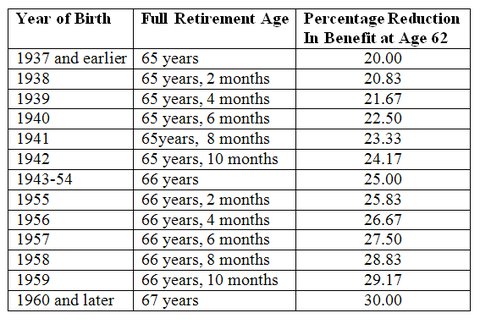

The reason is that workers did not receive full benefits at age 62, but 20 percent less than they would get if they waited until age 65. That was thought to be an actuarially fair adjustment so that whether one retired at age 62 or age 65, one received approximately the same aggregate lifetime Social Security benefits.

As the normal retirement age has increased from age 65 to 67, based on legislation enacted in 1983, the same actuarial adjustment has been made, as shown in the table.

Social Security Administration

Social Security Administration

Thus there is a huge financial price to be paid for drawing Social Security benefits early and an enormous payoff for delaying the decision to claim benefits. Unfortunately, I think many workers have a “use it or lose it” attitude, incorrectly thinking their benefits will be bumped up when they reach the full retirement age or ignorant that their benefits rise when receipt of them is delayed.

The fact is that the lower benefits people get by retiring early continues for their lifetime.

Another cost of taking Social Security before the normal retirement age is limiting the amount of earned income one may receive. Because of something called the earnings test, retirees lose $1 of benefits for every $2 of earnings they receive above $15,120 – equivalent to a 50 percent marginal tax rate on an annual income barely above the minimum wage. There is no loss of benefits for those above the normal retirement age.

What many people do not realize is that the same actuarial adjustment shown in the table continues past the normal retirement age. That is, one’s benefits continue to rise every month that one delays taking them until age 70. Those born in 1943 or later receive 8 percent more benefits a year for every year they wait to draw Social Security benefits past the full retirement age. This is called the delayed retirement credit.

People retiring at age 66 this year would get their full benefit. But if they wait until age 70, they would get 32 percent more. Social Security benefits are thus 57 percent higher at age 70 than at age 62.

The delayed retirement credit is an extraordinarily good deal – where else can one get a guaranteed 8 percent annual return these days? The lower interest rates are, the better deal it is.

Many people learn about the delayed retirement credit only after they have chosen to draw Social Security benefits, and they incorrectly believe they cannot go back. In fact, the Social Security Administration allows people to repay the benefits they have received, in effect resetting the clock.

This is not an option for most people, who lack the large lump-sum of cash they would need even if they knew it would pay off. But for someone who has the cash and simply made a mistake in drawing benefits too early, the payoff can be large, according to Laurence Kotlikoff of Boston University.

To be sure, many people in physically demanding jobs need early retirement, and some who are jobless have no choice but to take them the minute they qualify. But many can afford to wait, perhaps to age 70, before drawing Social Security benefits. Those who draw them too early risk extreme poverty in old age if they outlive their savings or are simply missing an easy way of increasing their retirement assets at a time when low interest rates make it hard for people to obtain interest income.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/05/one-recession-cost-is-lower-social-security-benefits/?partner=rss&emc=rss