Owen Zidar, a doctoral student in economics at the University of California, Berkeley, was previously a staff economist at the Council of Economic Advisers and, in 2008-9, an analyst at Bain Capital Ventures.

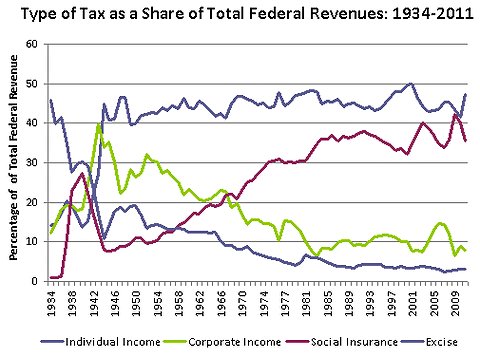

Payroll taxes and corporate income taxes accounted for an equal share of federal tax revenue in 1969. By 2009, payroll taxes generated more than six times as much revenue. We’ve become reliant on payroll taxes, and a goal of a tax overhaul should be to reform and reduce them, permanently.

First, some background. The share of federal tax revenues coming from payroll taxes has doubled since the 1970s, to about two-fifths of revenue. The payroll tax, underwriting social insurance programs, nearly surpassed the individual income tax as the single largest source of federal tax revenue in 2009.

Source: Office of Management and Budget Historical Table 2.2

Source: Office of Management and Budget Historical Table 2.2

Since payroll taxes finance Social Security and part of Medicare, cost growth in these programs pressures policy makers to raise those taxes. In particular, pressure from the Social Security disability insurance program and Medicare Part A has been intensifying.

The number of disability recipients has increased nearly sixfold since 1970. Disability outlays exceeded revenues by roughly $34 billion in 2011. And costs are likely to continue growing because shrinking labor market opportunities for noncollege-educated workers are likely to continue well past this recession. The Congressional Budget Office’s long-run projections for the program support this conclusion.

Pressure on the payroll tax from Medicare Part A is even worse. Health cost growth has steadily outpaced inflation, and the pattern shows no sign of abating. Fundamental economic forces – such as Baumol’s cost disease, which describes the phenomenon of rising costs in industries less conducive to automation – will most likely continue to increase health care costs steadily.

The primary argument for severing the link between these growing programs and the payroll taxes is that the tax is regressive: It uses a flat rate on income up to $110,100, does not apply to most income above that threshold and does not apply to nonlabor income, like capital gains. Because of this relatively regressive nature, payroll tax cuts tend to be a more effective stimulus than typical income tax cuts – and thus are a more effective way for Washington to respond to recessions.

Despite these features, AARP and other groups often resist payroll tax cuts out of a fear that the cuts will undermine the future of the safety net (even though the cuts are fully paid for out of general revenue). Permanently breaking the link between payroll taxes and both disability and Medicare would allow the tax code to become more progressive – and do more to offset inequality – without creating political problems when the business cycle calls for fiscal stimulus.

Obviously, the government would need other revenue if it severed the link between payroll taxes and the safety-net programs. One option would be to limit tax breaks, as Congress and the Obama administration have recently discussed. Others include phasing in a carbon tax, raising top marginal rates slightly or overhauling the tax code to use a progressive consumption tax that encourages saving.

The country is almost certain to face higher costs for health care and for an aging work force whose skills are being outpaced by technology. But there is no reason those costs must be borne by a regressive tax vulnerable to recurring struggles over economic policy.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/28/the-growing-burden-of-payroll-taxes/?partner=rss&emc=rss