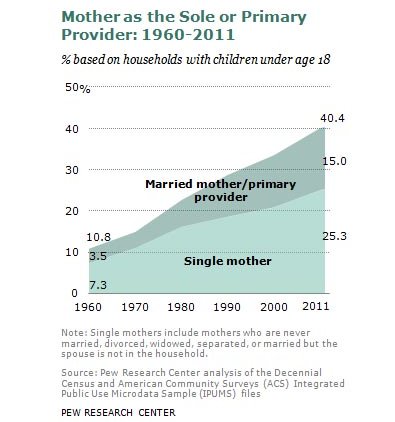

Four in 10 households with children under age 18 now include a mother who is either the sole or primary earner for her family, according to a Pew Research Center report released Wednesday. This share, the highest on record, has quadrupled since 1960.

The shift reflects evolving family dynamics.

For one, it has become more acceptable and expected for married women to join the work force. At the same time, it is more common for single women to raise children on their own. Most of those mothers who are chief breadwinners for their families — nearly two-thirds — are single parents.

The recession may have also played a role in pushing women into primary earning roles, as men are disproportionately employed in industries like construction and manufacturing that bore the brunt of the layoffs during the downturn. Women have benefited from a smaller share of the job gains during the recovery, though, given the many layoffs in the public sector, which disproportionately employs women.

Women’s attitudes toward working have also changed in the last few years. In 2007, before the recession officially began, 20 percent of mothers told Pew that their ideal situation would be to work full-time rather than part-time or not at all. The share had risen to 32 percent by the end of 2012.

The public is still divided about whether is it a good thing for mothers to work. About half of Americans say that children are better off if their mother is at home and doesn’t have a job. Just 8 percent say the same about a father. Most Americans acknowledge, though, that the increasing number of working women makes it easier for families “to earn enough to live comfortably.”

Demographically and socioeconomically, single mothers and married mothers are different from each others. The median family income for single mothers — who are disproportionately younger, black or Hispanic, and less educated — is $23,000. The median household income for married women who earn more than their husbands — more often white, slightly older and college-educated — is $80,000. The total family income is generally higher when the wife is the primary breadwinner, rather than the husband.

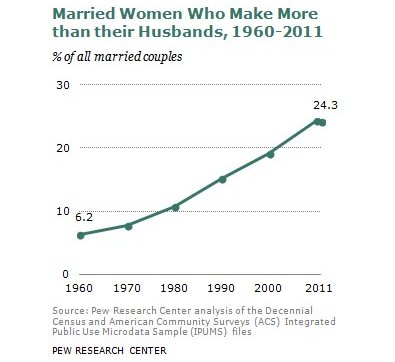

Such marriages are still relatively rare, though, even if their share is growing. Of all married couples, 24 percent include a wife who earns more, versus 6.2 percent in 1960. (The percentages are similar in regards to only married couples who have children.)

What this means for the stability of a marriage is unclear. In surveys, Americans say that they are accepting of marriages where the wife is the greater earner. Just 28 percent of Americans surveyed by Pew agreed that it is “generally better for a marriage if the husband earns more than his wife.”

The data on actual marriage and divorce rates suggests slightly different attitudes, though.

A new working paper by economists at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and the National University of Singapore found that, in looking at the distribution of married couples by income of husband versus wife, there is a sharp drop-off in the number of couples in which the wife earns more than half of the household income. This suggests that the random woman and random man are much less likely to pair off if her income exceeds his, the paper says.

The economists also found that wives with a better education and stronger earning potential than their husbands are less likely to work. In other words, women are more likely to stay out of the work force if there is a big risk that they will make more than their husbands.

And perhaps even more tellingly, couples in which the wife earns more report less satisfaction with their marriage and higher rates of divorce.

In certain ways, too, couples revert to more stereotypical sex roles when the wife brings in more money, with primary-breadwinning wives taking on a larger share of household work and child care.

“Our analysis of the time use data suggests that gender identity considerations may lead a woman who seems threatening to her husband because she earns more than he does to engage in a larger share of home production activities, particularly household chores,” the authors write.

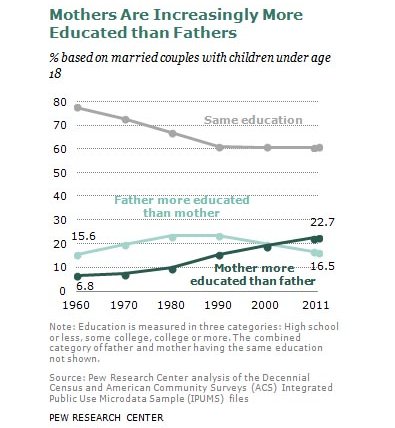

These patterns may, of course, change as the job market evolves. College degrees, for example, are becoming increasingly important to both finding and keeping a job. And women are more likely than men to get college degrees.

According to Pew, as of 2011, there were more married-couple families with children in which the wife was more educated than the husband. In 2011, in roughly 23 percent of married couples with children, the women had more education; in 17 percent of the couples the men had higher education. (The remaining 61 percent of two-parent families involve spouses with about equal levels of education.)

Norms are also changing: Newlyweds seem to show more openness to having the wife earn more than her husband than do longer-married couples. In about 30 percent of newly married couples in 2011, the wife earned more, versus just 24 percent of all married couples.

Americans have also become more accepting of single mothers. In an April survey, Pew found that 64 percent of Americans said the growing number of children born to unmarried mothers is a “big problem,” down from 71 percent in 2007. Republicans are more likely than Democrats or independents to be concerned about this trend.

Today’s single mothers are much more likely to have never been married than was the case for single mothers in the past, Pew found. In 1960, the share of never-married single mothers was just 4 percent; as of 2011, it had risen to 44 percent. Never-married mothers tend to make less money than their divorced or widowed counterparts, and are more likely to be a member of a racial or ethnic minority.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/30/business/economy/women-as-family-breadwinner-on-the-rise-study-says.html?partner=rss&emc=rss