Victor R. Caivano/Associated PressKaty Perry, an artist with EMI, which was sold last year, performing in Buenos Aires.

Victor R. Caivano/Associated PressKaty Perry, an artist with EMI, which was sold last year, performing in Buenos Aires.

Please, please take your seats.

Thank you once again for coming to DealBook’s annual closing dinner, where we toast and roast the world of finance — and look ahead to the new year.

We moved this year’s dinner from its usual spot in Manhattan to Paris so Nicolas Sarkozy and Angela Merkel (or Merkozy, as you know them) could attend, given their newfound influence on the markets and the global economy.

DealBook Column

View all posts

We thought of holding our gathering in Berlin, but then realized this might be the last year we’d be able to do Paris while France still has its AAA credit rating. Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, also pointed out that Société Générale could use the extra A.T.M. fees from all of you withdrawing tip money for the coat check.

Not everyone could make it. We mailed Jon Corzine several invitations, but initial reports indicated they were accidentally commingled with his holiday cards. He now says he misplaced the invitations completely and has “no idea” where they could be.

Silvio Berlusconi originally R.S.V.P.’ed “yes” when he saw the menu, but backed out when he learned that “16-year-old Caol Ila” was a single-malt whisky.

But it’s nice to see that so many of you could attend. The seating chart was a bit challenging. Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, is sitting next to Paul Volcker. They’ve agreed to take any discussion of the Volcker Rule outside.

I placed Lloyd Blankfein next to Mark Zuckerberg to ease the underwriting pitch for Facebook’s planned I.P.O. in 2012. I overheard Mr. Zuckerberg ask Mr. Blankfein what holiday gifts he had given his children. Then Mr. Zuckerberg added, “I’m not making small talk, Lloyd — it’s literally the only piece of your personal data I don’t have.”

By the way, Mr. Blankfein, the celebrity chef Mario Batali is graciously catering our dinner and has assured me that blood-sucking squid is not on the menu. I should also note that Mr. Batali has volunteered his services, perhaps to atone for declaring in 2011 that “the ways the bankers have kind of toppled the way money is distributed and taken most of it into their hands is as good as Stalin or Hitler and the evil guys.” Mario is preparing tagliatelle ai funghi e pancetta, which roughly translates to “please don’t put my restaurants out of business.”

I was hoping to invite some leaders of Occupy Wall Street to provide a little balance, but I still don’t know who’s in charge.

Finally, Andrew Mason of Groupon is here. It’s hard to overstate how big a year it was for Mr. Mason. His company went public, he became a billionaire and the daily coupon deals phenomenon he pioneered has seemingly swept the nation. Even his tablemate, Brian Moynihan, chief executive of Bank of America, is getting into the Groupon spirit with an offer of his own: three shares for the former price of one!

And now, on to the toasts and roasts of 2011:

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg NewsT-Mobile BlackBerry phones. ATT’s giant deal for T-Mobile fell apart last year.

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg NewsT-Mobile BlackBerry phones. ATT’s giant deal for T-Mobile fell apart last year.

BIGGEST LOSER ATT’s attempted $39 billion acquisition of T-Mobile may have been the worst merger idea of 2011. Both sides claim the regulatory winds shifted in Washington after the deal was announced. But anyone who was paying even a whiff of attention knew from Day 1 that regulators would block it.

Many have credited T-Mobile’s parent, Deutsche Telekom, and its legal team for walking away with a breakup fee worth about $6 billion. But T-Mobile winds up the biggest loser. The sour regulatory mood will make it harder for T-Mobile to pursue a deal with Sprint, which had been circling the company before ATT arrived. T-Mobile and Sprint are both in worse positions than they were a year ago; both companies have lost customers, and Sprint has a lot less money to spend on an acquisition.

As for Randall Stephenson, ATT’s chief, while the dead deal was clearly a mistake at least it was a relatively cheap one, costing the company only about two months’ worth of cash flow.

BIGGEST WINNER (FOR NOW) Richard Handler, the chief of Jefferies Company, probably deserves a pat on the back — and a double shot of that Caol Ila. He had a tough 2011.

His firm skirted a run on the bank after the collapse of MF Global put the spotlight on Jefferies as the American investment house most vulnerable to European sovereign debt. A credit rating downgrade only fanned the flames. But Mr. Handler stood firm, issuing lengthy denials of virtually any speculation that emerged. And he reduced the firm’s exposure to European sovereign debt by half just to prove to the market that he could. He had little choice, but so far, it’s been a winning strategy. Stay tuned for 2012.

THE RATINGS AGENCIES I’ve invited Douglas Peterson, the newly installed president of Standard Poor’s Ratings Services, mainly because the firm — and its industry peers — performed so miserably. You’re new, Mr. Peterson — you just came over from Citigroup, where you were chief operating officer — so we’ll let you eat with us this time.

But do take note: until the week before the collapse of MF Global, your peer agencies were giving that firm an investment-grade credit rating. As usual, the big ratings agencies did not sound the alarms until long after the fire was raging out of control. In S. P.’s case, it kept an investment-grade rating on MF Global until it filed for bankruptcy protection.

Remember Enron? A.I.G.? S. P. rated those companies with just as much insight. And Mr. Peterson, your firm’s downgrade of the United States last summer seemed aimed more at generating media attention and headlines than helping investors understand the risks of investing in United States Treasury securities. If anything, the downgrade proved how irrelevant the ratings agencies have become: Treasuries have since rallied.

So that you can gain a fuller appreciation of the anger the American public harbors for your firm and industry, I seated you next to Michael Moore, who recently said on Twitter: “Pres Obama, show some guts arrest the CEO of Standard Poors.”

CONSUMER ‘PROTECTION’ I invited both Elizabeth Warren and Richard Cordray to make a point: the bankers in this room waged a successful campaign to keep Ms. Warren from running the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2011. That, in turn, led President Obama to nominate Mr. Cordray, who was rejected by Republicans, again at the behest of Wall Street.

Whether either was the right person for the post is almost irrelevant. What’s clear is that Wall Street is doing everything it can to keep the agency from being able to do its job, and that’s a shame.

Even if you think the financial industry is overregulated or you don’t like the agency’s governance structure, all this political maneuvering sends an awful message to the public: Wall Street banks are actively trying to stymie a start-up agency charged with protecting consumers’ money.

SLEEPER DEAL OF 2011 The sale of EMI Publishing for $2.2 billion to a group led by Sony was hardly the biggest deal of the year, but it might have been the most interesting and undercovered transaction of 2011.

Consider this: EMI’s recorded music unit — the sexy part of the business that produces albums by the likes of Katy Perry and Coldplay — was sold on the same day for $1.9 billion to the Universal Music Group, a division of the French conglomerate Vivendi.

That means the typically boring publishing business, which deals with song copyrights, was sold for more, and it went to a Sony-led group that included boldface-name investors like the media mogul David Geffen; the estate of Michael Jackson; Blackstone’s GSO Capital Partners unit; Mubadala, the investment arm of Abu Dhabi; and Jynwel Capital of Malaysia.

The transaction was orchestrated by Robert Wiesenthal, chief financial officer of the Sony Corporation of America, demonstrating that in this age of digital media uncertainty, the predictable fee stream of a homely business like music publishing has a higher value than an ego-driven trophy asset like music recording.

Watch for more deals of this sort in 2012.

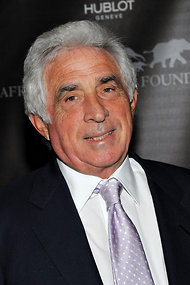

Jamie Mccarthy/Getty Images For The Promotion FactoryTheodore Forstmann, a pioneer in private equity, died in November after a battle with brain cancer.

Jamie Mccarthy/Getty Images For The Promotion FactoryTheodore Forstmann, a pioneer in private equity, died in November after a battle with brain cancer.

REMEMBERING TEDDY Finally, let’s have a brief moment of silence for Theodore Forstmann, one of the pioneers of the private equity business, who died in November after a battle with brain cancer.

In an often-scorned industry, he embodied its best parts. Bold, often brash, sometimes difficult, he was ultimately an entrepreneur’s entrepreneur. And he was introspective enough to have serious doubts about the use of leverage and speak out publicly about it. Most important of all, he donated much of his fortune to underprivileged children.

I’d be remiss if I did not also mention another industry legend who died in 2011: F. Warren Hellman, co-founder of Hellman Friedman, the West Coast buyout firm that once owned Levi Strauss Company and Nasdaq. He, too, gave away much of the “2 and 20” he made.

At a time when the “1 percent” is being ridiculed as selfish and greedy, it is worth remembering the enormous good Mr. Forstmann and Mr. Hellman accomplished. I attended Mr. Forstmann’s funeral and was struck less by the Masters of the Universe in the pews than by the dozens of schoolchildren in attendance — most of them recipients of scholarships financed by Mr. Forstmann.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=2083af78c7bec8bd283ed8b88812fa12