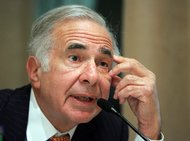

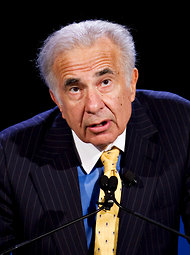

Mark Lennihan/Associated PressCarl C. Icahn, the activist investor, in 2007.

Mark Lennihan/Associated PressCarl C. Icahn, the activist investor, in 2007.

Carl C. Icahn lived up to his word on Friday, offering a sweetener to his alternative to a $24.4 billion leveraged buyout of Dell Inc. by adding a warrant to his stock buyback plan.

In a letter to Dell shareholders, Mr. Icahn and his partner, Southeastern Asset Management, proposed giving shareholders a warrant to buy a share in the struggling computer company at $20 apiece for every four shares that they tender. That’s in addition to buying back 1.1 billion shares at $14 each. The activist investor says the entire package is worth $15.50 to $18 a share.

The move is the latest gambit by Mr. Icahn to sway shareholders away from supporting a $13.65-a-share takeover bid by Michael S. Dell and the investment firm Silver Lake, an offer that he has criticized as too low. The increased jockeying for investors’ loyalties comes ahead of a vote scheduled for Thursday on Mr. Dell’s offer.

Earlier this week, Mr. Icahn urged Dell shareholders to seek so-called appraisal rights for their holdings, in case the leveraged buyout is approved. That would allow investors to potentially receive more — or less — for their stock, once a Delaware state judge delivers a pronouncement on the company’s worth.

To advisers to Mr. Dell and to a special committee of Dell’s board, it appeared to be a desperate move and an effort to force the would-be buyers into raising their bid. But in his letter on Friday, Mr. Icahn contended that he was not seeking merely a bump in price. Instead, he argued that his efforts were aimed at replacing Mr. Dell as chief executive and leading a turnaround of the company himself.

“We are completely committed to our proposal and believe that it is economically better for stockholders than the Michael Dell/Silver Lake freeze out transaction,” he wrote. “We are also completely committed to bringing in management that we expect to be far superior to Michael Dell who we believe has had an abysmal record during the last three years.”

Mr. Icahn again took exception to a report by Institutional Shareholder Services, the proxy advisory firm, recommending that investors vote for Mr. Dell’s offer. His argument: I.S.S., as the firm is known, assumed that the leveraged buyout would lead to be a speedy payout to shareholders, while the stock buyback plan was uncertain and could drag out.

The billionaire activist contended that he believed his proposal could close faster than the proposed takeover. But he neglected to mention that his plan requires the election of an entirely new board, something that Mr. Dell — who owns a 16 percent stake — is unlikely to support.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/07/12/as-promised-icahn-adds-to-his-bid-for-dell/?partner=rss&emc=rss