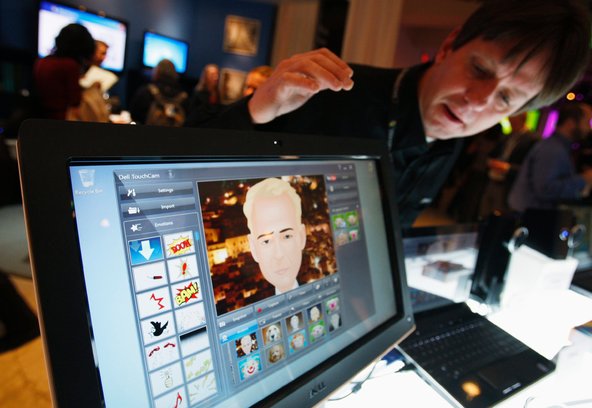

Shannon Stapleton/ReutersA Dell Sx2210t touch monitor running Windows 7 in 2009.

Shannon Stapleton/ReutersA Dell Sx2210t touch monitor running Windows 7 in 2009.

The effort to take Dell private has gained a prominent, if unusual, backer: Microsoft.

The software giant is in talks to help finance a takeover bid for Dell that would exceed $20 billion, a person briefed on the matter said on Tuesday. Microsoft is expected to contribute up to several billion dollars.

An investment by Microsoft — if it comes to pass — could be enough to push a leveraged buyout of the struggling computer maker over the goal line. Silver Lake, the private equity firm spearheading the takeover talks, has been seeking a deep-pocketed investor to join the effort. And Microsoft, which has not yet made a commitment, has more than $66 billion in cash on hand.

Microsoft and Silver Lake, a prominent investor in technology companies, are no strangers. The private equity firm was part of a consortium that sold Skype, the online video-chatting pioneer, to Microsoft for $8.5 billion nearly two years ago. And the two companies had discussed teaming up to make an investment in Yahoo in late 2011, before Yahoo decided against selling a minority stake in itself.

A vibrant Dell is an important part of Microsoft’s plans to make Windows more relevant for the tablet era, when more and more devices come with touch screens. Dell has been one of the most visible supporters of Windows 8 in its products.

That has been crucial at a time when Microsoft’s relationships with many PC makers have grown strained because of the company’s move into making computer hardware with its Surface family of tablets.

Frank Shaw, a spokesman for Microsoft, declined to comment.

If completed, a buyout of Dell would be the largest leveraged buyout since the financial crisis, reaching levels unseen since the takeovers of Hilton Hotels and the Texas energy giant TXU. Such a deal is taking advantage of Dell’s still-low stock price and the abundance of investors willing to buy up the debt issued as part of a transaction to take the company private. And Silver Lake has been working with Dell’s founder, Michael S. Dell, who is expected to contribute his nearly 16 percent stake in the company to a takeover bid.

Yet while many aspects of the potential deal have fallen into place, including a potential price of up to around $14 a share, talks between Dell and its potential buyers may still fall apart.

Shares of Dell closed up 2.2 percent on Tuesday, at $13.12. They began rising after CNBC reported Microsoft’s potential involvement in a leveraged buyout. Microsoft shares slipped 0.4 percent, to $27.15.

Lucas Jackson/ReutersDell’s founder, Michael S. Dell, attended the unveiling of Microsoft’s Windows 8 operating system last year in New York.

Lucas Jackson/ReutersDell’s founder, Michael S. Dell, attended the unveiling of Microsoft’s Windows 8 operating system last year in New York.

Microsoft’s lending a hand to Dell could make sense at a time when the PC industry is facing some of the biggest challenges in its history. Dell is one of Microsoft’s most significant, longest-lasting partners in the PC business and among the most committed to creating machines that run Windows, the operating system that is the foundation of much of Microsoft’s profits.

But PC sales were in a slump for most of last year, as consumers diverted their spending to other types of devices like tablets and smartphones. Dell, the third-biggest maker of PCs in the world, recorded a 21 percent decline in shipments of PCs during the fourth quarter of last year from the same period in 2011, according to IDC.

In a joint interview in November, Mr. Dell and Steven A. Ballmer, Microsoft’s chief executive, exchanged friendly banter, as one would expect of two men who have been in business together for decades.

Mr. Dell said Mr. Ballmer had gone out of his way to reassure him that Microsoft’s Surface computers would not hurt Dell sales.

“We’ve never sold all the PCs in the world,” said Mr. Dell, sitting in a New York hotel room brimming with new Windows 8 computers made by his company. “As I’ve understood Steve’s plans here, if Surface helps Windows 8 succeed, that’s going to be good for Windows, good for Dell and good for our customers. We’re just fine with all that.”

Microsoft has been willing to open its purse strings in the past to help close partners. Last April, Microsoft committed to invest more than $600 million in Barnes Noble’s electronic books subsidiary, in a deal that ensures a source of electronic books for Windows devices. Microsoft also agreed in 2011 to provide the Finnish cellphone maker Nokia billions of dollars’ worth of various forms of support, including marketing and research and development assistance, in exchange for Nokia’s adopting Microsoft’s Windows Phone operating system.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/01/22/microsoft-may-back-dell-buyout/?partner=rss&emc=rss