Casey B. Mulligan is an economics professor at the University of Chicago. He is the author of “The Redistribution Recession: How Labor Market Distortions Contracted the Economy.”

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Employment can be a better indicator of labor market activity than unemployment, because unemployment is not the only way that a person can be without work.

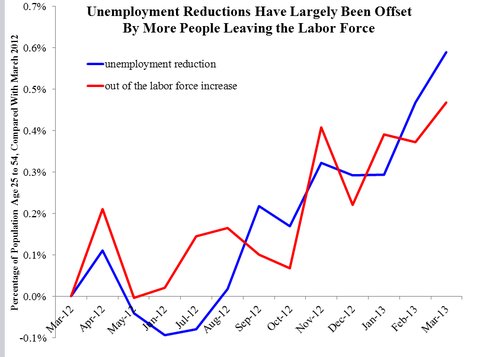

The blue series in the chart below shows the reduction in unemployment since March 2012, expressed as a percentage of the population (e.g., in a population of 100 million, 0.1 percentage points means 100,000 people and 0.5 percentage points means 500,000.) In order to correct for the movement of baby boomers into retirement, I used Bureau of Labor Statistics data only for people 25 to 54 years old (this group is about 124 million and has been falling a little). Over the subsequent year, and especially since mid-2012, unemployment was reduced significantly.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bureau of Labor Statistics

But reduced unemployment is not the same as more employment, because the third labor force classification is “out of the labor force.” Neither the unemployed nor those out of the labor force have a job, but only the unemployed are actively looking for one.

The red series in the chart shows that the “out of the labor force” ranks have increased roughly as much as unemployment has been reduced, and the difference between the blue and the red series indicates the change in the fraction of the population that is employed. For the months when the blue series is above the red series, employment per capita has increased since March 2012.

Because the blue series hardly exceeds the red series, if at all, the large majority of the reduction in unemployment has been associated with offsetting increases in people out of the labor force.

While the reduction in unemployment and the growth in the out of the labor force more or less cancel each other out, jobs are at least being created fast enough to absorb the growth in the working-age population. That additional population increases demand, which contributes to the jobs being created.

Retirements and going to school could increase the number of people out of the labor force, but the data I’ve shown are for an age group in which retirement and schooling are rare. For the 25-to-54 age group, “out of the labor force” typically represents people who are finding ways to get by without working.

Some people moving out of the labor force devote their time to caring for their young children while their spouses obtain cash income for the family. That some of the growth in those out of the labor force has occurred among married people suggests that such specialization in the family could be part of the story. But the fact that this group is growing especially among unmarried people suggests that family specialization explains at best a minority of the aggregate changes.

Unemployment insurance benefits are paid only to people who report that they are actively looking for work. Some unemployed have long been skeptical that they can find a good job and are just going through the motions of job search to satisfy the unemployment program’s requirements (see this testimony to a House subcommittee by Stacey G. Reece, co-owner of a recruitment firm in Gainesville, Fla., who said he witnessed people “applying for jobs only to protect their status for unemployment insurance”).

When such a person’s unemployment benefits run out, he may look less actively for work, which changes his classification from unemployed to out of the labor force.

The termination of unemployment benefits can, and sometimes does, have the opposite effect, because the loss of income can make out-of-work people more seriously consider accepting a low-paying job. But unemployment insurance is by no means the only safety-net program. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as food stamps) is a major and newly expanded safety-net program and does not require its beneficiaries to work or be looking for work. Curiously, SNAP has been expanding while the unemployment rate falls.

People without jobs increasingly take part in the disability insurance program, which does not require people to look for work because “disability” means that the person is unable to work. Medicaid is another major safety program that does not require its participants to work.

A significant part of the recent reductions in the unemployment rate may reflect movements of people between safety net programs rather than any significant change in their job-finding prospects.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/10/varieties-of-not-working/?partner=rss&emc=rss