Casey B. Mulligan is an economics professor at the University of Chicago. He is the author of “The Redistribution Recession: How Labor Market Distortions Contracted the Economy.”

Small businesses have spoken out against the Affordable Care Act, but medium-size businesses, customers and taxpayers may be the ones ultimately harmed.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

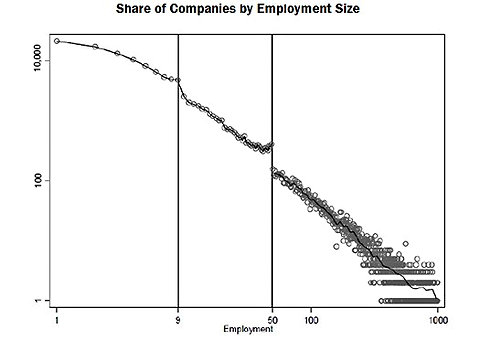

Beginning next year, the Affordable Care Act will penalize employers that fail to offer health insurance to their employees. Because small employers are especially unlikely to offer health insurance (see Table 3 in this paper from the Congressional Budget Office), and large businesses are likely to avoid the penalties because they already offer insurance, the penalties seem like an attack on small business.

But the Affordable Care Act simultaneously rewards employees at small companies by heavily subsidizing their purchases of health insurance on the exchanges created by the law. Because employees cannot take the subsidies with them if they switch to a large company offering health insurance, the subsidies are, in effect, subsidies to the small businesses themselves, helping them compete more cheaply in the market for employees.

Employees at the smallest companies, with fewer than 50 employees, are eligible to receive the subsidies, even though their employers are exempt from the penalties.

Indeed, some medium-size businesses that currently offer health insurance say they find the smaller company “penalty plus subsidy” combination attractive and plan to drop their health insurance plans in order to partake in it, too, even though their participation will entail a penalty.

The Affordable Care Act also created tax credits for small business that are already available. These credits perhaps have too many strings attached to be attractive to employers, because only 770,000 employees (in an economy with more than 130 million) worked for employers claiming the credit in 2010 (see Page 9 of this report from the Government Accountability Office). The Affordable Care Act also promised to provide small-business employees a choice of health plans, but implementation of that plan has been pushed back until 2015.

Many small businesses are not as good with bureaucracy and red tape as large businesses are – that’s one reason they did not offer health insurance in the first place. The employee subsidies coming online next year are pretty complicated, as evidenced by the 21-page application that must be completed by each employee, and the fact that any one year’s subsidy has to be estimated based on historical employee data, advanced from the Internal Revenue Service to the insurer, and then later reconciled when the employee’s family income for the year can be fully documented.

I suspect that large businesses will have human resource personnel dedicated to helping company employees complete the application and obtain and accurately reconcile the subsidy to which they are entitled. Employees at smaller business may have to fend for themselves.

We also have to remember that businesses compete for customers and for employees. A business that experiences a little direct harm from the act may benefit on the whole because competitors are harmed more. This is especially true because of the heavy penalty the law puts on businesses that expand from 49 to 50 employees: that one hire will cost the employer $40,000 annually in penalties, on top of that employee’s usual salary and benefits.

Thus, the type of company that may benefit the most from the law is not necessarily large or small but a company with small competitors that have been looking for opportunities to expand their market share, and in the process bring the number of their employees to more than 49.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/03/small-companies-and-the-affordable-care-act/?partner=rss&emc=rss