CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

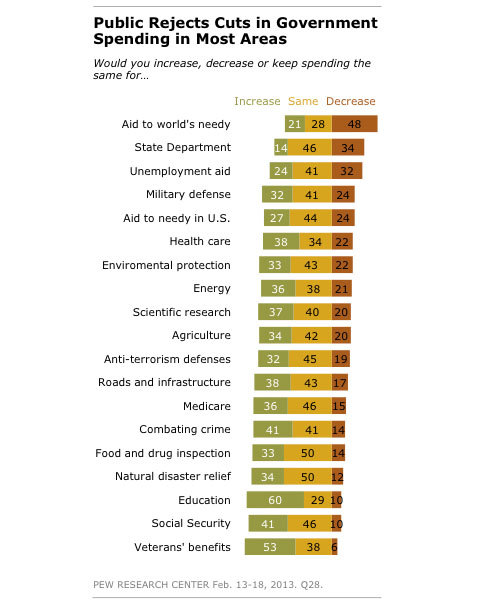

As the sequester looms, it’s worth noting that there’s no significant federal spending category that a majority of Americans wants to cut:

Survey was conducted among 1,504 adults. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points.

Survey was conducted among 1,504 adults. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points.

That chart comes from a Pew Research Center poll conducted Feb. 13-18. In every category except for “aid to world’s needy,” more than half of the respondents wanted either to keep spending levels the same or to increase them. In the “aid to world’s needy” category, less than half wanted to cut spending.

This is part of the problem with heeding any public concerns about getting the budget under control. According to Pew, 70 percent of Americans say it is essential for Washington to pass major legislation to reduce the federal budget deficit this year. But they can’t identify anything worth axing, and it’s not as if tax increases are so terribly popular, either.

By the way, Pew asked similar questions about what categories of government spending to cut in 2011. There has been little change since then, with the exception of attitudes toward military spending. In the most recent poll, 24 percent said the government should cut spending for the military, compared to 30 percent two years ago.

Note that the military would bear a major share of the sequestration-related spending cuts, and as a result much has been written in the last few months about the scary consequences that such cuts would cause. So it’s possible public attitudes have shifted in response to greater coverage of this spending category.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/22/americans-want-to-cut-spending-they-just-dont-know-what-to-cut/?partner=rss&emc=rss