Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

In debates on health work force policy, it is frequently argued that medical education is a public good, because it benefits society as a whole.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

The implication is that tuition charges at medical schools should be zero or close to zero. Many nations in the industrialized world follow that policy, although they have also kept tuition low for most college students.

Most economists disagree with characterizing higher education as a public good. Only the individual receiving a professional education – including the M.D. degree — owns the human capital that the graduation documents certify to exist.

Medical graduates can use their human capital any way they wish. They can treat patients, do medical research or use their knowledge as business consultants to health-related companies or as financial analysts in the financial markets, as some of them do.

There may be some positive spillover for society as a whole from having this privately owned human capital produced, and these effects (called externalities by economists) might warrant some public subsidies toward the production of that human capital. That argument could be extended to many other forms of human capital, as well — e.g., engineers, scientists, nurses.

According to a fact sheet published by the American Association of Medical Colleges, annual tuition and fees at public medical schools in 2011-12 amounted to $30,753, and the total cost of attendance was $51,300. The comparable averages for private medical schools were $48,258 and $69,738. To most Americans, these will seem staggering amounts.

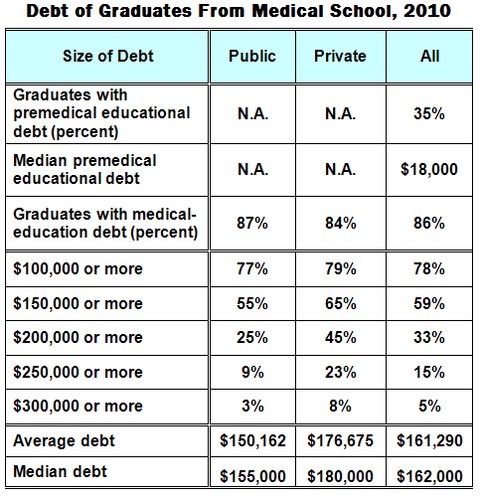

Which brings me to the sizable debt with which, almost uniquely in the world, American medical students now graduate. The association routinely collects data on these debts. A good summary of the most recent data, for 2010, can be found on the previously identified fact sheet, and I created this table from that source.

American Association of Medical Colleges

American Association of Medical Colleges

As the table shows, some of the students’ accumulated debt by time of graduation from medical school was incurred to finance a liberal arts undergraduate education. The $18,000 shown in the table is actually on the low side. According to the Project on Student Debt, college seniors who graduated in 2010 had an average debt of $25,250, with a range among campuses of $950 to $55,250 a student. Individual students at private colleges may have even larger debts. And debt collectors are doing a thriving business collecting these debts.

Amortization of the large debt accumulated by medical students will clearly take a bite of the income they will earn in medical practice. But at least there will be a sizable future income stream to absorb the hit. Many other college graduates have much smaller incomes or are in even direr straits.

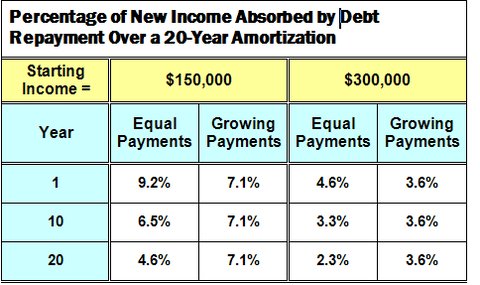

The table below conveys a rough indication of what the amortization of medical-school debt might mean for individual students.

In this table I have assumed that the student modeled here had average debt of $161,300 upon graduation from medical school. From that debt I deducted $24,400, the amount to which $18,000 of debt upon graduation from a liberal arts college would grow in four years at a compound interest rate of 7.9 percent (that’s at the high end of the interest rate medical students are charged on debt). The remainder is debt related strictly to the medical education of the student.

I assume that after residency, the practicing physician has a starting net income (after practice costs) of $150,000 or $300,000, and that these incomes will grow at an annual compound growth rate of 3.5 percent over time. Physician incomes vary considerably across specialties and even within specialties.

To get a feel for the data, readers may want to look at several surveys of doctors’ pay.

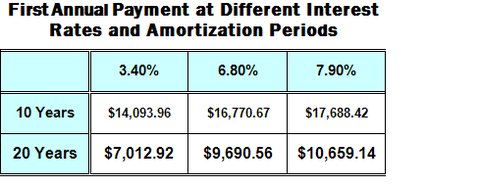

According to the association’s fact sheet, students pay an interest rate of 6.8 percent on Stafford loans; for lower-income students, the rate is a subsidized 3.4 percent. For Direct Plus loans, students or their parents pay a rate of 7.9 percent, the rate I used in the table.

Finally, I assume two distinct amortization models. Under one, students pay back their debt with flat annual (or monthly) payments over 20 years. That payment is $13,840 a year. Under the alternative approach, the annual amortization payment rises in step with the assumed annual increase in physician income. The first annual payment in that approach is $10,659.

The data in the table represent these annual debt-amortization payments as a percentage of physician net income in years one, 10 and 20 of medical practice.

Clearly, these payments are a noticeable burden, even over 20 years. For amortization over 10 years, they would naturally be higher. On the other hand, the numbers would decline sharply with reductions in the interest rate charged. The table below illustrates the sensitivity of the first-year payment to interest rates and amortization horizon for the payment stream that increases in step with assumed increases in practice income.

The annual amortization payments would be particularly burdensome for primary care physicians, with their relatively lower incomes. That fact is a potential policy lever Congress might employ if it took seriously people’s lament that America is suffering from an acute shortage of primary care physicians.

I shall muse about that and other options in a future post.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/14/the-debt-of-medical-students/?partner=rss&emc=rss