Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

The roughly 50 million Americans covered by the federal Medicare program have a choice of receiving their benefits under the traditional, free-choice, fee-for-service Medicare program or from a private, managed-care Medicare Advantage plan. The private plans have a steadily increasing number of enrollees — currently 13 million, or 27 percent of beneficiaries.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

A fundamental question that has engaged health-policy researchers and commentators for some time is whether coverage of Medicare’s standard benefit package under Medicare Advantage plans is cheaper or more expensive than it is under traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

The answer is yes.

At the risk of going over ground already covered in Economix and in the scholarly literature on the subject, this answer may warrant some explanation.

The latest round in the debate over the question was begun in August 2012 by Zirui Song, David M. Cutler and Michael E. Chernew in their paper “Potential Consequences of Reforming Medicare Into a Competitive Bidding System.” In that paper, the authors explored how much more above their regular Part B premiums the elderly would have had to pay in 2009 to either a Medicare Advantage plan or to traditional Medicare if the much-debated Ryan-Wyden plan for Medicare had been in place that year.

That plan would have established a Medicare Exchange — a federal version of the insurance exchanges envisaged under the Affordable Care Act — on which Medicare beneficiaries could have chosen among private health plans that would compete with traditional Medicare on the same terms, that is, on the same competitive platform.

Each private plan would have had to offer a benefit package that covered at least the actuarial equivalent of the benefit package provided by the traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Medicare’s contribution (or “premium support”) to the full premium for any of these choices, including traditional Medicare, would have been equal to the “second-least-expensive approved plan or fee-for-service Medicare” in the beneficiary’s county, whichever was least expensive. That premium support payment would have been adjusted upward for the poor and the sick and downward for the wealthy.

Drs. Song, Cutler and Chernew estimated that on the basis of a national average the second-lowest bids actually submitted by private health plans in the various counties and regions in 2009 were 9 percent below the comparable average per-beneficiary cost of traditional Medicare.

Close to 70 percent of the beneficiaries in 2009 would have had to pay more than their traditional Part B premiums to stay in traditional Medicare. About 90 percent of beneficiaries in private Medicare Advantage plans in 2009 would have paid more than they actually did in that year.

These figures suggest substantial savings for United States taxpayers, although not for beneficiaries. Mindful of the beneficiaries, the authors ended their paper with reservations about the Ryan-Wyden plan, rather than an enthusiastic endorsement.

In an acerbic comment on that paper, published in The Weekly Standard, James C. Capretta and Yuval Levin saw in the authors’ numbers strong support for Ryan-Wyden or similar market-driven plans and sharply took the authors to task for their interpretation of the data.

But so far the Ryan-Wyden plan is only theory. In fact, as is by now widely known, enrollment of Medicare beneficiaries in private Medicare Advantage plans actually has cost taxpayers considerably more than it would have cost had the same beneficiaries stayed in traditional fee-for-service Medicare. As the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, or Medpac, observes in its March 2009 report to Congress (see Page 252):

In 2009, payments to MA plans continue to exceed what Medicare would spend for similar beneficiaries in FFS. MA payments per enrollee are projected to be 114 percent of comparable FFS spending in 2009, compared with 113 percent in 2008. This added cost contributes to the worsening long-range financial sustainability of the Medicare program.

These extra payments to Medicare Advantage plans in 2009 have been estimated at $11.4 billion.

How, then, is one to reconcile these contradictory claims over the likely benefits from competitive bidding for Medicare’s business by private health plans?

The answer can be found in the bureaucratic arrangement enacted as part of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003.

Remarkably, the Republican authors of that bill in the White House and in the Congress — usually self-proclaimed champions of market-driven competition – eschewed that approach in favor of a statutory, administrative algorithm so complex as to defy description within the space of this post (for details see this Commonwealth Fund document).

Most likely, the bureaucratic route was chosen at the behest of private insurers that would have insisted that a truly competitive approach required traditional Medicare to be treated as just another health plan competing with private plans on identical terms. In the process, however, the industry managed to extract from Congress remarkably generous terms.

Under those terms, Medicare’s benchmark for a county or region is not based on competitive bids at all but is administratively set with appeal to the average spending per beneficiary in traditional fee-for-service Medicare in the county or region in which a beneficiary resides, albeit with a variety of adjustments that push the resulting county or regional benchmarks considerably above per-beneficiary spending under traditional Medicare. Austin Frakt neatly illustrates the resulting benchmarks graphically.

In this system, the private plans do submit premium bids for a statistically average (“standard”) beneficiary in the relevant county or region, and for Medicare’s standard benefit package. These so-called standard bids are the actual bids used in the Song, Cutler and Chernew analysis.

If a Medicare Advantage plan submits for a county or region a standard bid above Medicare’s relevant benchmark, the plan is paid by Medicare a “base rate” (for the statistically average beneficiary) equal to that benchmark. It means, of course, that the plan is paid more than the relevant per beneficiary spending under traditional Medicare. The Medicare Advantage plan must then collect the difference between its bid and the benchmark from the enrollee (on top of the Part B premium the enrollee must pay in any event).

Medicare’s payment to the plan for a particular enrollee, however, is not just the “base rate.” The actual payment quite properly reflects the individual beneficiary’s actuarial risk. That multiplicative adjustment is clearly illustrated in Figure 1 of this Medpac publication, where it is called “CMS-HHS Weight.”

On the other hand, if a Medicare Advantage plan’s bid is below Medicare’s relevant benchmark, then that plan is paid its bid plus a fixed percentage of the difference between its bid and the benchmark, a so-called rebate. Most of that rebate must be spent by the plan on added benefits not in Medicare’s standard benefit package, although some undoubtedly flows into profits.

For 2012, the fixed percentage for the rebates ranges from 67 to 73 percent, depending on a quality rating score. After 2014, the fixed percentages will be 50, 65 and 70 percent, depending on the plan’s quality rating.

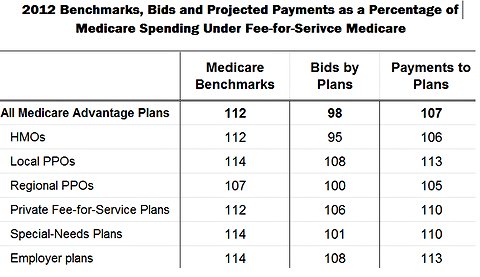

The table below, a reproduction of Table 12-3 of the March 2012 Medpac Report to Congress, exhibits the nationwide averages of the Medicare benchmarks, the standard bids by plans and the projected payments to plans under this complex “bidding” system. The different types of plans (health maintenance organizations, preferred provider organizations and private fee-for-service plans) were described in an earlier post. Special-needs plans concentrate on patients requiring home care or other special care. Employer plans are offered by particular employers.

Medpac, Medicare Payment Policy, Report to Congress, March 2012

Medpac, Medicare Payment Policy, Report to Congress, March 2012

It is seen that all Medicare Advantage plans together and especially H.M.O.’s do appear to bid less on average than per-beneficiary spending under traditional Medicare. That would seem to justify the argument that, on average, under genuine competition Medicare Advantage plans as a group would be cheaper than traditional Medicare.

These differentials — here two percentage points for all Medicare Advantage plans and five percentage points for H.M.O.’s — are a bit misleading, however, because the traditional Medicare spending figures include add-ons that are not part of providing health care to Medicare beneficiaries. Traditional Medicare makes payments for graduate medical education and so-called disproportionate share payments to hospitals that treat a disproportionate share of Medicaid patients or uninsured patients. Private Medicare Advantage plans do not have to make such payments.

There is the additional suspicion that even after risk adjustment, the private Medicare Advantage plans still benefit to some extent from favorable actuarial risk selection.

So the question remains: Is coverage of Medicare’s standard benefit package under private Medicare Advantage plans cheaper or more expensive than it is under traditional fee-for-service Medicare?

Readers now know why the correct answer is yes.

Whether Congress will ever have the temerity to foist upon vendors to the Medicare program truly raw price competition remains an open question. Traditionally vendors to government have preferred administered prices, for reasons evident in the table above.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/04/the-complexities-of-comparing-medicare-choices/?partner=rss&emc=rss