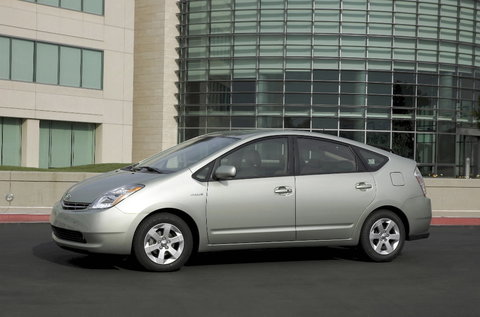

Associated Press A 2007 Toyota Prius.

Associated Press A 2007 Toyota Prius.

Like any used car, a used hybrid vehicle can save you money, both on the purchase price and on the insurance you carry. But there are special factors to take into account when shopping for a hybrid, beyond what you’d look for when buying a traditional used car, says John O’Dell, the “green car” editor at the automotive site Edmunds.com.

More than 2 million “conventional” gasoline-electric hybrid cars (those that don’t plug in to recharge the battery) have been sold since they first came on the market, more than a decade ago. Now, more hybrids are becoming available as used cars, offering the chance for buyers to own a fuel-efficient model at a lower price. There are an estimated 415,000 used hybrids on the market right now — mostly Toyota Prius models, since the Prius has accounted for about half of new hybrid sales, according to Edmunds.

As with any used car, it’s important to have a mechanic inspect the vehicle — but finding a mechanic knowledgeable about hybrids is critical, because the cars employ some complex technology. One source for finding knowledgeable hybrid technicians: the Auto Career Development Center, which lists qualified hybrid repair shops.

You shouldn’t assume that dealerships have trained hybrid mechanics, he said; it’s best to ask. “If they say ‘no,’ move on,” he advises.

One plus: Because hybrid cars use the electric motor to help slow the car down, a hybrid’s brakes usually last longer than those on conventional cars, Mr. O’Dell said. If maintenance records indicate frequent brake jobs, the hybrid may have been driven hard by its prior owner — so you should make sure other mechanical parts aren’t worn excessively, too.

One potential cost is a replacement battery pack for hybrids. All hybrids are required by federal regulations to carry a minimum of a 100,000-mile, eight-year battery warranty; some states, like California, require even longer warranty periods. But some tests have shown that the batteries used to power the hybrids’ electric motors last much longer. “They can last for a long time,” said Mr. O’Dell. So if a car is less than five years old and has fewer than 100,000 miles on it, battery life shouldn’t be a concern, he said.

If the car is older than five years and has more than 100,000 miles on it, you might want to factor in the potential for a battery replacement. Right now, a new replacement battery for Toyota’s 2004-9 Prius models sells for less than $2,200, Edmunds found. Honda sells replacement batteries for the 2005 to 2011 Civic hybrids for $1,700, while a replacement for a Nissan Altima hybrid runs about $4,900. However, Consumer Reports notes that battery packs can be purchased from auto salvage yards for as little as $500.

Prices for used hybrids vary by market, depending on the supply available. In Southern California, where cars are relatively plentiful and demand is strong, listings include a 2006 “base” model Prius with 58,000 miles for $16,000, and a 2008 “touring” Prius with 83,000 miles for $15,000, Mr. O’Dell says.

A new 2013 Prius, meanwhile, starts at about $24,000 and can go to about $32,000, depending on trim levels and options.

Have you purchased a used hybrid vehicle? How did it work out for you?

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/30/tips-for-buying-a-used-hybrid-car/?partner=rss&emc=rss