Carl Richards

Carl Richards

Carl Richards is a financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at the BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published last year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

This post has been updated to switch the labels on the axes.

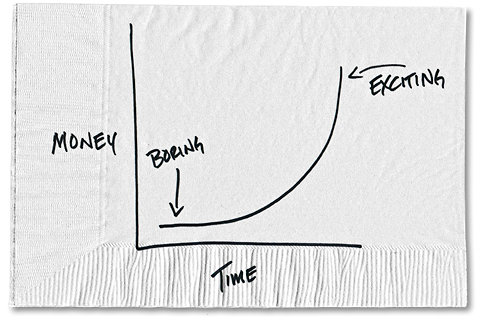

You’ve probably heard that starting early is one of the best investing decisions you can make. That’s because investing done right is short-term boring but long-term exciting.

The reason? The reality of compound interest. Let me explain.

Many people talk about the power of compound interest. Albert Einstein is rumored to have called it the most powerful force in the universe.

Now, I suspect he probably didn’t really say that, but whether he did or not, it’s a point that we often miss in the discussion about compound interest. Despite it being one of the most powerful forces in the universe, it’s not one of the most exciting – at least in the short term. Nothing really great happens until after years and years of discipline and patience.

Take this silly (but true!) story that’s often told to demonstrate how powerful compound interest is: If you start with one penny and double it every day for 30 days, you’ll end up with $5,368,709.12.

I should add a disclaimer here that if anyone offers you an investment that will double in value every day, you should run as fast as you can in the other direction. But let’s get back to the main point. Sure, compound interest has a powerful outcome, but it takes an awfully long time to become fun and exciting.

Now take a look at our penny example again. One penny doubled is 2 cents. Two cents turns to $0.04, $0.04 to $0.08, $0.08 to $0.16, $0.16 to $0.32, $0.32 to $0.64, and $0.64 to $1.28. Nothing very exciting there.

But when you stick with it, it’s that last few times when the figure doubles that it gets very, very exciting. You’re looking at $1,342,177.28 becoming $2,684,354.56, and $2,684,354.56 doubling to $5,368,709.12.

That’s the case with our investments, too. It’s not very exciting at the beginning, but compounding becomes a powerful force after years of patience and discipline.

Let me give you a real example: Say you have Sarah, who decides at 25 to save $1,000 a month. She does that for 10 years. And then she stops. Then you have Roger, who waits until he’s 35, and he saves $1,000 a month for 30 years. They both earn 7 percent on their savings.

Now, 30 years after she stops contributing Sarah would have $1,262,089.05. But Roger, who would have put away three times as much as Sarah, would only have $1,133,529.44.

The reason Sarah only saved a third as much as Roger but ended up with more money is because she started earlier.

But here’s what you have to understand: Nothing too incredible happened during that first 10 years that Sarah was saving and Roger wasn’t. The exciting part happens years down the road. So we have to be patient and disciplined, counting on the fact that compounding is going to do its work in its own time.

It’s kind of like planting an oak tree. As Warren Buffett said in an interview with News Inc, “Someone’s sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree long ago.” The same thing applies to compound interest. We have to live through the boring parts in order to reap the benefits down the road.

And here’s the key. Every day you wait you’re not cutting off the flat end of the curve like I’ve drawn in the sketch. You’re cutting off the steep end. You can’t skip the boring part and get right to the excitement.

That’s why we have to get started investing today.

I know that many of us didn’t start early. Maybe you haven’t even started yet. But this is an incredibly important concept. If you’re 45 and haven’t started saving, you don’t want to be 55 and in the same (actually a much worse) position. So start now.

It’s also an incredibly important concept to share with your kids, your grand kids, or even the neighbor’s kids down the block. We have to start teaching them that if they want to enjoy the shade of that oak tree, they better darn well plant the seed now.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/07/investing-money-plus-lots-of-time-equals-excitement/?partner=rss&emc=rss