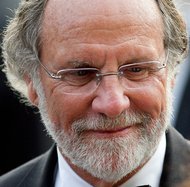

Jay Mallin/Bloomberg NewsRepresentative Randy Neugebauer, the chairman of the House Financial Services Subcommittee, wrote a letter to the New York Fed on Monday.

Jay Mallin/Bloomberg NewsRepresentative Randy Neugebauer, the chairman of the House Financial Services Subcommittee, wrote a letter to the New York Fed on Monday.

Congress widened its inquiry into the interest-rate manipulation scandal, pressing the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to further disclose its knowledge of the multiyear scheme.

On Monday, the oversight panel of the House Financial Services Committee sent a letter to the New York Fed seeking volumes of records about the London interbank offer rate, or Libor, a measure of how much banks charge each other for loans. Lawmakers are demanding that the New York Fed detail its communications with employees from all 16 banks that help set the interest rate, which affects the trillions of dollars in mortgages and other loans.

The letter follows an Congressional request that the New York Fed turn over transcripts from phone calls its officials had with just one bank: Barclays.

In June, the British bank became the first to settle accusations that it tried to manipulate Libor for its own benefit. Authorities around the globe are investigating more than 10 other big banks for their role in rigging the interest rate.

The initial transcripts released this month showed that the New York Fed learned about wrongdoing at Barclays in 2008. That revelation called into question whether the New York Fed pursued the matter fully.

Libor Explained

“We know that we’re not posting um, an honest” rate, a Barclays employee told a New York Fed official in April 2008, according to transcripts. At the time, because high borrowing costs were a sign of poor health, banks were submitting artificially low rates to project a better image of their finances.

The transcript, among other documents, only fed the firestorm over what regulators might have known about the rate-rigging scandal. The New York Fed and other authorities are under scrutiny for failing to thwart the illegal activities that, at Barclays, continued to 2009.

“There are still many outstanding questions that merit further investigation,” Representative Randy Neugebauer, the chairman of the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, wrote in the letter on Monday.

The latest request is likely to produce reams of memos and e-mails. The subcommittee is demanding “all communications and documents” between the New York Fed and the 16 banks over a five-year span, from 2007 to 2012. The New York Fed, which has until Sept. 1 to provide the documents, must also turn over its internal documents and any correspondence with authorities in the United States and abroad.

The New York Fed has defended its actions, saying it briefed regulators about the broad problems with Libor.

But lawmakers have questioned why the New York Fed, despite its awareness of misconduct at Barclays, did not refer the illegal acts to regulators or the Justice Department. Instead, the New York Fed circulated in June 2008 a plan to fix Libor, producing a six-point plan to revamp the rate-setting process.

“As you know, the role of government is to ensure that our markets are run with the highest standards of honesty, integrity and transparency,” Mr. Neugebauer wrote. “Therefore, any admission of market manipulation — regardless of the degree — should be swiftly and vigorously investigated.”

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/07/23/congress-presses-new-york-fed-for-more-details-on-rate-rigging-scandal/?partner=rss&emc=rss