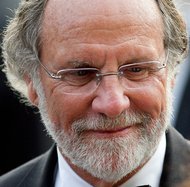

Michael Reynolds/European Pressphoto AgencyJon S. Corzine, MF Global’s former chief executive, testifying at a House hearing into the collapse of his firm.

Michael Reynolds/European Pressphoto AgencyJon S. Corzine, MF Global’s former chief executive, testifying at a House hearing into the collapse of his firm.

9:05 p.m. | Updated

WASHINGTON — Jon S. Corzine, who came to Washington in 2001 as a Democratic senator from New Jersey, made a humbling return on Thursday, defending his tenure as MF Global’s top executive and sounding a note of contrition about the brokerage firm’s startling collapse.

Mr. Corzine told the House Agriculture Committee that he was “stunned” when he learned late on Oct. 30 that about $1 billion of customer money could not be located, a discovery that thwarted a sale of the firm and led to its filing for bankruptcy. Regulators and the Federal Bureau of Investigation are now hunting for the money and examining potential wrongdoing at the firm.

Thursday’s testimony was his first public comments since the bankruptcy and came after the committee voted last week to subpoena him.

The former senator insisted that he always tried to “do the right thing.”

“I never intended to break any rules,” said Mr. Corzine, dressed in a dark suit but without his trademark sweater vest. “I know I had no intention to ever authorize the transfer of segregated moneys. I know what my intentions were.” Mr. Corzine has not been accused of any wrongdoing.

He did not rule out possible wrongdoing at MF Global. In theory, an employee may have misused customer cash after misinterpreting the chief executive’s words, he said.

Still, over three hours of testimony, Mr. Corzine danced carefully around questions touching on the scandal of the missing funds, using phrases like “never intended” and “not to my knowledge.”

And he offered little insight into the whereabouts of the missing money. He surmised that one potential cause of the shortfall was the “extraordinary number of transactions during MF Global’s last few days,” calling it a “chaotic” period that was “extremely difficult” to “reconstruct.”

Yet it was not known until Thursday whether Mr. Corzine would directly respond to the lawmakers’ questions at all.

“Considering the circumstances, many people in my situation would almost certainly invoke their constitutional right to remain silent — a fundamental right that exists for the purpose of protecting the innocent,” he said. “Nonetheless, as a former United States senator who recognizes the importance of Congressional oversight, and recognizing my position as former chief executive officer in these terrible circumstances, I believe it is appropriate that I attempt to respond to your inquiries.”

Mr. Corzine, who ran Goldman Sachs before entering politics, eagerly defended his decision to invest heavily in European sovereign debt, saying that it was part of a crucial push to return the firm to profitability. The firm had a $6.3 billion bet on the debt of five European nations.

“At the time that MF Global entered into the transactions,” he said, “I believed that its investments in short-term European debt securities were prudent.”

The MF Global board, he said, approved the risk limits for the trades, which were set on a country-by-country basis. At times, he said, the firm exceeded those limits and “it took appropriate steps” to reduce the risk.

When MF Global filed for bankruptcy, Mr. Corzine said the firm was “within the risk limits set by the board of directors.” He said that he resigned from the firm on Nov. 4 at the request of a senior member of the board.

Mr. Corzine, who was defeated for re-election as governor of New Jersey in 2009, also defended his dealings with regulators. Months before the firm failed, he began a personal lobbying blitz, urging regulators at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission to weaken a rule that would rein in the use of customer funds. He took his pitch directly to the agency’s chairman, Gary Gensler, who worked for Mr. Corzine at Goldman Sachs in the 1990s.

Their relationship has come under a microscope on Capitol Hill. Mr. Gensler recused himself from the investigation of MF Global after Senator Charles E. Grassley, Republican of Iowa, raised questions about Mr. Gensler’s past acquaintance with Mr. Corzine.

Now, some Republicans are criticizing Mr. Gensler for stepping back at such a crucial moment for the agency. Representative Timothy V. Johnson, Republican from Illinois, said on Thursday that it was “entirely unacceptable” for Mr. Gensler to not testify at the hearing. He also criticized what he has called a “Goldman Sachs fraternity.”

Jill E. Sommers, a Republican member of the futures commission, has taken over the lead role on the case and testified on Thursday. Lawmakers asked her whether the agency should have sounded the alarm about MF Global before its final days.

Ms. Sommers replied that the agency was “not the frontline regulator.” That job belongs to for-profit exchanges like the CME Group.

Lawmakers were not satisfied.

“It appears to me that no one has learned a thing; that Wall Street is still operating as if 2008 never happened,” said Collin C. Peterson of Minnesota, the committee’s ranking Democrat.

Mr. Corzine will remain a regular presence on Capitol Hill for weeks. Two other Congressional panels, the Senate Agriculture Committee and the oversight arm of the House Financial Services Committee, have also demanded that he testify next week.

The House panel on Thursday also heard testimony from the firm’s regulators, including Ms. Sommers and the CME Group.

But throughout the stop-and-start proceedings, the attention was centered on Mr. Corzine. And with the world watching, he began his testimony with a mea culpa.

“I sincerely apologize, both personally and on behalf of the company, to our customers, our employees and our investors, who are bearing the brunt of the impact of the firm’s bankruptcy,” Mr. Corzine said.

“My sadness, of course, pales in comparison to the losses and hardships that customers, employees and investors have suffered as a result of MF Global’s bankruptcy.”

In its final days, MF Global tapped its customers’ accounts to meet its own financial obligations, people briefed on the matter have said. The act violated a fundamental Wall Street regulation that firms never commingle customer money with company funds.

Mr. Corzine told the House committee that he learned of the missing money about 11 p.m. on Oct. 30. “I remain deeply concerned about the impact that the unreconciled and frozen funds have had on MF Global’s customers and others,” he said.

The former senator at times seemed comfortable sitting on the other side of the hearing room. When faced with questions about MF Global’s complex trading, he took a professorial tone, explaining the intricacies of his business and even cracking an occasional smile.

And while lawmakers peppered Mr. Corzine with questions about his European sovereign debt bet and the missing money, they kept a cordial tone with their former colleague. One congressman even congratulated the former Goldman executive on achieving considerable wealth.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=30b8db92a4145752ad4fc5eeb9e9c357