CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

Fortuitously, in the midst of the contentious Chicago teachers union strike, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has released its annual report on the state of education and investment in education around the developed world. It might help provide some context for what Chicago teachers are fighting over.

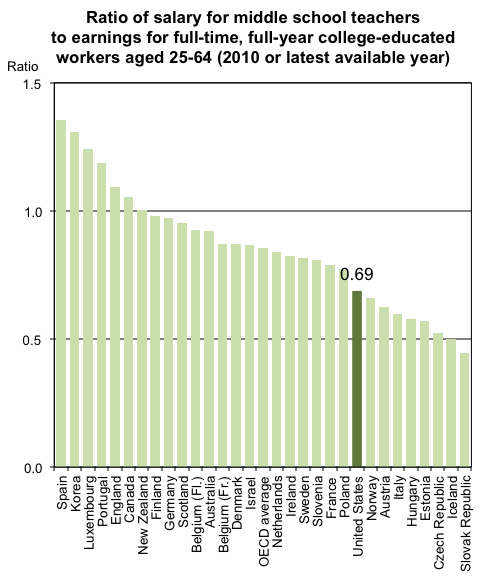

Here’s one particularly striking figure from the report, showing the ratio of teacher salaries to the earnings of other workers who went to college:

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The United States spends a lot of money on education; including both public and private spending, America spends 7.3 percent of its gross domestic product on all levels of education combined. That’s above the average for the O.E.C.D., where the share is 6.2 percent.

The annual spending per student by educational institutions of all levels is also higher in the United States than it is in any other developed country.

Despite the considerable amount of money channeled into education here, teaching jobs in the United States are not as well paid as they are abroad, at least when you consider the other opportunities available to teachers in each country.

In most rich countries, teachers earn less, on average, than other workers who have college degrees. But the gap is much wider in the United States than in most of the rest of the developed world.

The average primary-school teacher in the United States earns about 67 percent of the salary of a average college-educated worker in the United States. The comparable figure is 82 percent across the overall O.E.C.D. For teachers in lower secondary school (roughly the years Americans would call middle school), the ratio in the United States is 69 percent, compared to 85 percent across the O.E.C.D. The average upper secondary teacher earns 72 percent of the salary for the average college-educated worker in the United States, compared to 90 percent for the overall O.E.C.D.

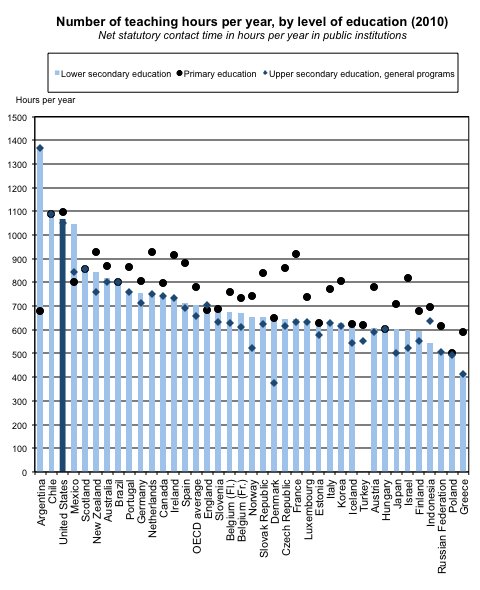

American teachers, by the way, spend a lot more time teaching than do their counterparts in most other developed countries:

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Year of reference for Argentina is 2009. Numbers for the United States, England, Denmark, Japan, Indonesia and the Russian Federation refer to actual teaching hours.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Year of reference for Argentina is 2009. Numbers for the United States, England, Denmark, Japan, Indonesia and the Russian Federation refer to actual teaching hours.

So tell me: Given the opportunity costs of becoming a teacher instead of using your college degree to enter another, more remunerative field, are the psychic rewards of teaching great enough to convince America’s best and brightest to become educators?

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/11/does-it-pay-to-become-a-teacher/?partner=rss&emc=rss