Every new report about the American health care economy seems to confirm the same pattern: spending is rising at the slowest pace in decades.

In 2013, health spending will grow less than 4 percent for the fourth time in five years and shrink as a share of the economy, according to the number crunchers at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

In February, the Congressional Budget Office forecast that spending on Medicare and Medicaid over the coming decade would be $382 billion less than it had predicted last August.

The new numbers have provided an unexpected dose of optimism to the debate about squaring a budget deficit that is expected to widen sharply as the baby-boom generation enters retirement.

But this optimism might be premature, because nobody knows for sure how long the slowdown in medical spending will continue. And there is reason to suspect it may not last long. The pace of health spending could pick up again as soon as the economy recovers. It depends on what is causing the decline: newfound efficiency or simply economic decline.

Economists in the White House argue that it’s mostly about efficiency – partly in response to the Affordable Care Act. People who lose their job will spend less on medical care, of course. But the White House economists concluded that the jump in unemployment over the last five years explains less than a fifth of the slowdown in health care spending.

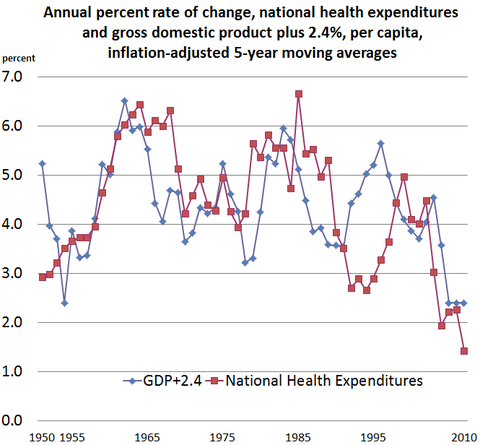

Victor R. Fuchs of Stanford University concludes, however, that the dismal economy might be playing a much larger role. In a recent report published in The New England Journal of Medicine, he points to a tight relationship between health spending and economic growth: over most of the last six decades, health spending per person has grown roughly 2.4 percentage points faster than the economy.

Source: Victor Fuchs, Stanford University

Source: Victor Fuchs, Stanford University

Slower health spending over the last couple of years could prove to be a harbinger for the future. But it is way to early to tell. Mr. Fuchs notes that short-term fluctuations do a terrible job at predicting trends over the longer term: over the last 60 years the correlation between changes in spending over two years and over 20 years has been, in fact, negative.

For all the hope that we’ve entered a new era of health spending, the odds are good that once the economy starts growing faster, medical spending will surge.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/19/health-spending-watching-for-a-rebound/?partner=rss&emc=rss