Casey B. Mulligan is an economics professor at the University of Chicago. He is the author of “The Redistribution Recession: How Labor Market Distortions Contracted the Economy.”

A number of industries can expect big changes in employee health insurance in the next year or two, while others will continue with business as usual.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Beginning next year, states and the federal government intend to create opportunities for families to purchase health insurance, separate from their employers, through insurance “exchanges” in the states. Insurers and the federal government will heavily advertise the new plans. Most important, middle- and low-income families may qualify for valuable federal subsidies that will serve to reduce premiums and out-of-pocket health costs.

To qualify for subsidized exchange plans, workers cannot be offered affordable insurance by their employers. Paradoxically, employers will create subsidy opportunities for their middle- and low-income employees whenever they fail to offer health insurance.

On the other hand, an employer dropping its health insurance next year will put its high-income employees in a tough spot, because they will have to buy insurance on their own without the tax advantages they had in the past by obtaining health insurance through their employer. As a result, employers with relatively many high-income employees will be under pressure to keep their insurance, whereas an employer of middle- and low-income employees may find them asking for health insurance to be dropped from the employee benefit menu.

Administrative costs, rising premiums and other costs have already made a number of employers lukewarm about health insurance, but they offered it in order to attract employees who do not care to be uninsured or to end up on Medicaid. The new insurance opportunities that become available next year may give their employees enough of an alternative that the lukewarm employers can drop their plans.

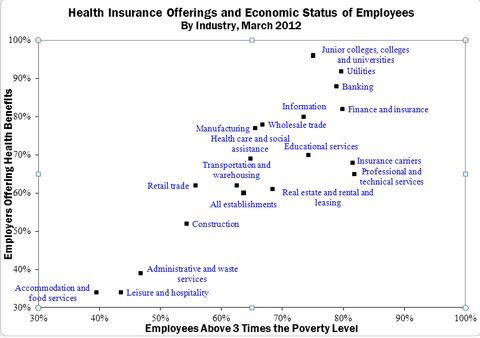

Both of these situations are closely correlated across industries, which leaves me to suspect that we can readily predict the industries that will retain employer insurance and predict those that will drop whatever health benefits they currently have. The scatter diagram below displays Bureau of Labor Statistics data on several industries according to the percentage of their employees in families above three times the poverty line (horizontal axis) and the percentage of employers offering health benefits as of March 2012 (vertical axis).

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Bureau of Labor Statistics

I measured employees relative to three times the poverty line because that is the family income threshold beyond which the new exchange subsidies are less valuable than the income tax preference for employer-sponsored health insurance.

Industries like colleges, utilities and banking almost always offer health insurance, and about 80 percent of their employees will be getting a better deal on employer health insurance than they would from the exchange plans because their families are above three times the poverty line. For these reasons, I am confident that these industries will continue to offer health insurance to their employees in much the same way that they have in the past.

A couple of industries like “accommodation and food services” (i.e., restaurants), leisure and hospitality, administrative and waste services, and construction already have a mix of employers in terms of their health insurance offerings, so it would not be unusual from an industry perspective for those that currently have health plans to drop them during the next couple of years.

Moreover, the diagram shows how 45 to 60 percent of their employees do not come from families above three times poverty and therefore will have a significant federal health insurance subsidy waiting for them as soon as their employers drop coverage.

Employers that do not offer health insurance may be subject to penalties, but the penalties are not levied based on part-time employees, or levied on small employers, and even the penalties levied will be less than the subsidy opportunities created by an employer of middle- and low-income people that fails to offer health insurance.

For these reasons, I suspect that the stories we will hear about employers dropping insurance will disproportionately come from the industries shown in the lower left part of the scatter diagram, which collectively employ about 25 million people. Some employers in these industries have already discussed such plans.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/15/patterns-of-health-insurance-changes/?partner=rss&emc=rss