Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of the coming book “The Benefit and the Burden.”

On Nov. 21, Newt Gingrich, who is leading the race for the Republican presidential nomination in some polls, attacked the Congressional Budget Office. In a speech in New Hampshire, Mr. Gingrich said the C.B.O. “is a reactionary socialist institution which does not believe in economic growth, does not believe in innovation and does not believe in data that it has not internally generated.”

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Mr. Gingrich’s charge is complete nonsense. The former C.B.O. director Douglas Holtz-Eakin, now a Republican policy adviser, labeled the description “ludicrous.” Most policy analysts from both sides of the aisle would say the C.B.O. is one of the very few analytical institutions left in government that one can trust implicitly.

It’s precisely its deep reservoir of respect that makes Mr. Gingrich hate the C.B.O., because it has long stood in the way of allowing Republicans to make up numbers to justify whatever they feel like doing.

For example, Republicans frequently assert that tax cuts, especially for the rich, generate so much economic growth that they lose no revenue. This theory has been thoroughly debunked, most recently by the tax cuts of the George W. Bush administration, which, according to C.B.O., reduced revenues by $3 trillion. Nevertheless, conservative groups like the Heritage Foundation (where I worked in the 1980s) still peddle the snake oil that the Bush tax cuts paid for themselves.

Mr. Gingrich has long had special ire for the C.B.O. because it has consistently thrown cold water on his pet health schemes, from which he enriched himself after being forced out as speaker of the House in 1998. In 2005, he wrote an op-ed article in The Washington Times berating the C.B.O., then under the direction of Mr. Holtz-Eakin, saying it had improperly scored some Gingrich-backed proposals. At a debate on Nov. 5, Mr. Gingrich said, “If you are serious about real health reform, you must abolish the Congressional Budget Office because it lies.”

This is typical of Mr. Gingrich’s modus operandi. He has always considered himself to be the smartest guy in the room and long chaffed at being corrected by experts when he cooked up some new plan, over which he may have expended 30 seconds of thought, to completely upend and remake the health, tax or education systems.

Because Mr. Gingrich does know more than most politicians, the main obstacles to his grandiose schemes have always been Congress’s professional staff members, many among the leading authorities anywhere in their areas of expertise.

To remove this obstacle, Mr. Gingrich did everything in his power to dismantle Congressional institutions that employed people with the knowledge, training and experience to know a harebrained idea when they saw it. When he became speaker in 1995, Mr. Gingrich moved quickly to slash the budgets and staff of the House committees, which employed thousands of professionals with long and deep institutional memories.

Of course, when party control in Congress changes, many of those employed by the previous majority party expect to lose their jobs. But the Democratic committee staff members that Mr. Gingrich fired in 1995 weren’t replaced by Republicans. In essence, the positions were simply abolished, permanently crippling the committee system and depriving members of Congress of competent and informed advice on issues that they are responsible for overseeing.

Mr. Gingrich sold his committee-neutering as a money-saving measure. How could Congress cut the budgets of federal agencies if it wasn’t willing to cut its own budget, he asked. In the heady days of the first Republican House since 1954, Mr. Gingrich pretty much got whatever he asked for.

In addition to decimating committee budgets, he also abolished two really useful Congressional agencies, the Office of Technology Assessment and the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. The former brought high-level scientific expertise to bear on legislative issues and the latter gave state and local governments an important voice in Congressional deliberations.

The amount of money involved was trivial even in terms of Congress’s budget. Mr. Gingrich’s real purpose was to centralize power in the speaker’s office, which was staffed with young right-wing zealots who followed his orders without question. Lacking the staff resources to challenge Mr. Gingrich, the committees could offer no resistance and his agenda was simply rubber-stamped.

Unfortunately, Gingrichism lives on. Republican Congressional leaders continually criticize every Congressional agency that stands in their way. In addition to the C.B.O., one often hears attacks on the Congressional Research Service, the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Government Accountability Office.

Lately, the G.A.O. has been the prime target. Appropriators are cutting its budget by $42 million, forcing furloughs and cutbacks in investigations that identify billions of dollars in savings yearly. So misguided is this effort that Senator Tom Coburn, Republican of Oklahoma and one of the most conservative members of Congress, came to the agency’s defense.

In a report issued by his office on Nov. 16, Senator Coburn pointed out that the G.A.O.’s budget has been cut by 13 percent in real terms since 1992 and its work force reduced by 40 percent — more than 2,000 people. By contrast, Congress’s budget has risen at twice the rate of inflation and nearly doubled to $2.3 billion from $1.2 billion over the last decade.

Mr. Coburn’s report is replete with examples of budget savings recommended by G.A.O. He estimated that cutting its budget would add $3.3 billion a year to government waste, fraud, abuse and inefficiency that will go unidentified.

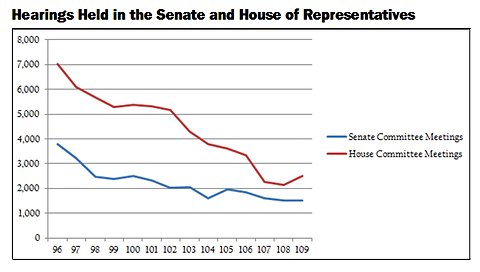

For good measure, Mr. Coburn included a chapter in his report on how Congressional committees have fallen down in their responsibility to exercise oversight. The number of hearings has fallen sharply in both the House and Senate. Since the beginning of the Gingrich era, they have fallen almost in half, with the biggest decline coming in the 104th Congress (1995-96), his first as speaker.

Brookings InstitutionAfter Newt Gingrich became speaker of the House in the 104th Congress, the number of hearings held there fell far more sharply than in the Senate.

Brookings InstitutionAfter Newt Gingrich became speaker of the House in the 104th Congress, the number of hearings held there fell far more sharply than in the Senate.

In short, Mr. Gingrich’s unprovoked attack on the C.B.O. is part of a pattern. He disdains the expertise of anyone other than himself and is willing to undercut any institution that stands in his way. Unfortunately, we are still living with the consequences of his foolish actions as speaker.

We could really use the Office of Technology Assessment at a time when Congress desperately needs scientific expertise on a variety of issues in involving health, energy, climate change, homeland security and many others. And given the enormous stress suffered by state and local governments as they are forced by Washington to do more with less, an organization like the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations would be invaluable.

It is essential that Congress not cripple what is left of its in-house expertise. Gutting the G.A.O. and abolishing the C.B.O. would be acts of nihilism. Any politician recommending such things is unfit for office.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=a7507aa7b68f184d3be08141b882c13c