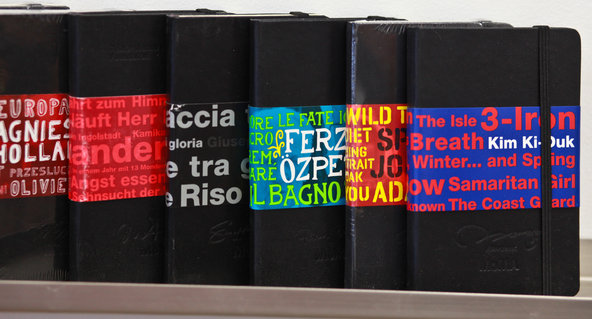

Fred R. Conrad/The New York TimesMoleskine’s leather-bound notebooks have been used by the likes of Picasso and van Gogh.

Fred R. Conrad/The New York TimesMoleskine’s leather-bound notebooks have been used by the likes of Picasso and van Gogh.

12:52 p.m. | Updated LONDON – From Hemingway to the public markets, shares of the vintage notebook company Moleskine fell modestly on the first day of trading on Wednesday after the Italian company raised $314 million through an initial public offering.

Moleskine, whose leather-bound notebooks have been used by the likes of Picasso and van Gogh, is the latest European company to turn to the capital markets despite recent uncertainty caused by the bank crisis in Cyprus.

Backed by the private equity firm Syntegra Capital, the Italian notebook maker also is the first company to list on the Milan stock exchange since the luxury clothing designer Brunello Cucinelli raised just over $200 million in April 2012.

Faced with renewed investor interest in equities, European companies and their backers have been quick to take advantage.

The total value of I.P.O.’s across the Continent doubled in the first quarter of the year, to $7 billion, compared with the period a year earlier, according to the data provider Dealogic.

The new offerings have been spread across a number of industries, though real estate I.P.O.’s have garnered particularly attention. The German property company LEG Immobilien, which is owned by the Goldman Sachs investment fund Whitehall, pocketed 1.3 billion euros ($1.7 billion) in the Continent’s largest I.P.O. during the first quarter.

Moleskine, whose backers also include the European venture capital firm Index Ventures, said last week that it had priced its new offering at 2.30 euros a share, which was the midpoint of the expected price range.

In trading in Milan on Wednesday, its shares rose as much as 3.9 percent before falling back slightly by early afternoon. It closed at 2.28 euros a share, down .87 percent from its offering price.

Goldman Sachs, UBS and Mediobanca managed the offering for Moleskine.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/04/03/shares-of-moleskine-rise-in-trading-debut/?partner=rss&emc=rss