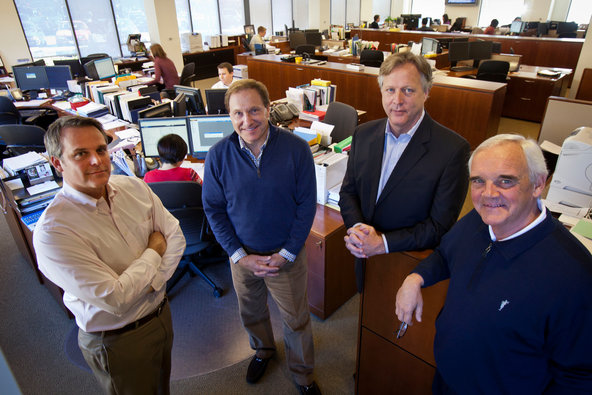

Peter DaSilva for The New York TimesFrom left, Jason Bogardus, senior vice president; Mark Douglas, managing director of wealth management; Greg Vaughan, managing director; and Robert Dixon, managing director of wealth management, at Morgan Stanley’s offices in Menlo Park, Calif.

Peter DaSilva for The New York TimesFrom left, Jason Bogardus, senior vice president; Mark Douglas, managing director of wealth management; Greg Vaughan, managing director; and Robert Dixon, managing director of wealth management, at Morgan Stanley’s offices in Menlo Park, Calif.

PALO ALTO, Calif. — Sam Odio expected a few congratulatory e-mails when he sold Divvyshot, his online photo-sharing service, to Facebook last April for millions of dollars.

Instead, his in-box was flooded with pitches from Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and other Wall Street firms looking to manage his newfound wealth. Goldman has the inside track, having courted him with an exclusive factory tour of Tesla, the electric sports-car maker, and tickets to a screening of the final Harry Potter film.

“They sure know the way to a geek’s heart,” said Mr. Odio, 27.

Wall Street, as always, is going where the money is — and right now that is Silicon Valley. The latest Internet boom means there are more newly minted millionaires, and even billionaires, than at any time since the technology bubble a decade ago.

Many are brilliant young entrepreneurs and computer engineers. But for all their knowledge, the technology executives, many of whom are fresh out of college, are relatively clueless when it comes to estate planning.

“Betting the ranch on building a widget for the Facebook platform is very different than managing a long-term nest egg,” said Jay Backstrand, a vice president at JPMorgan Chase’s private bank.

Wall Street is more than happy to help — for a fee. Banks charge roughly 1 percent for overseeing a wealthy investor’s portfolio. Though that may not sound like a lot, it adds up when billions of dollars are involved.

Financial firms are salivating over the wealth being created. Facebook is readying an initial public offering that will most likely value it near $100 billion. Employees and directors at Zynga own more than a third of the online game company, which went public in December at $7 billion. The list of prospects is long: Groupon is worth $12.2 billion; LinkedIn, $6.8 billion; and Pandora, $1.9 billion.

Peter DaSilva for The New York TimesGreg Vaughan speaking with a client at Morgan Stanley’s private wealth management offices in Menlo Park, Calif.

Peter DaSilva for The New York TimesGreg Vaughan speaking with a client at Morgan Stanley’s private wealth management offices in Menlo Park, Calif.

Banks are casting a wide net for potential clients. At Facebook, Wall Street brokers are wooing executives, rank-and-file employees and administrative staff members. Morgan Stanley has a dual strategy, with one team of advisers responsible for senior executives at large technology start-ups and another for lower-level employees. Chris Dupuy, who leads Merrill Lynch’s wealth management team in the Pacific Northwest, recruits from the C-Suite to the “corporate cafeteria.”

“Someone’s going to capture this wealth,” said Derek Fowler, a wealth adviser at Morgan Stanley. “We just want to make sure we’re out there.”

Banks are aggressively expanding in Northern California, even as they retrench globally. JPMorgan opened a 10,000-square-foot office in Palo Alto, Calif., a hub of venture capital activity. Goldman, which is eliminating some 1,000 jobs worldwide, plans to increase staff in San Francisco by 30 percent over the next year. UBS has more than doubled its wealth management staff in the area since 2008. “It’s very competitive,” said Joseph A. Camarda, who relocated from Philadelphia to lead Goldman’s wealth management group in San Francisco. “I think every firm has an A-list team out here.”

This feeding frenzy is familiar to those who experienced the last Internet boom. In the late 1990s, Wall Street descended on Silicon Valley, luring clients from marquee names like Yahoo and eBay. But after scouting clients from start-ups that flopped when the bubble burst in 2000, some banks pulled back.

This time, banks seem more aggressive. With start-ups growing faster than ever before because of developments in computing technology, it is critical to build relationships early. The emergence of secondary exchanges has allowed employees to sell shares before companies go public. Google, Facebook and other Internet giants are snapping up start-ups to spur growth, turning founders into overnight millionaires.

Geoff Lewis, the co-founder and chief executive of TopGuest, a mobile application acquired by ezRez Software in December, said he was surprised by the banks’ persistence. He was contacted by Goldman, UBS and Merrill within hours of the deal’s announcement.

“One bank, when I didn’t respond, asked if I’d like to attend a Sharks game with one of their managing directors to get to know them better,” Mr. Lewis said. He passed.

Advisers often tap existing clients for prospects and also scour industry sites, like TechCrunch or AllThingsD. The professional social network LinkedIn is an indispensable tool, with its database of start-up employees.

Personal connections matter, too. Andy Ellwood, an executive at Gowalla. a mobile application, received several e-mails when the service was sold to Facebook in December. But Goldman had already been in touch for months, after a broker met Mr. Ellwood’s girlfriend at a book club.

“In the middle of a lot of things going on, I didn’t want to deal with an overly aggressive sales person,” he said. “It was nice to know that there’s a friendly adviser, just a phone call away.”

But Silicon Valley’s culture of flip-flops and T-shirts represents a challenge to Wall Street’s staid, button-down brokers. Mutual funds and other investments don’t typically appeal to entrepreneurs, who often use spare funds to finance other start-ups.

Travis Kalanick, a co-founder of Uber, an on-demand car service, hired a broker a few years ago. But he grew skeptical after the adviser suggested a complicated investment that would make money only if a stock index fell within a narrow range.

“I felt like I was walking into a casino, where the dealer knew more than I did,” said Mr. Kalanick, who eventually left the brokerage firm.

Banks have been slow to adopt the latest technological innovations, which could make for a tougher sell in Silicon Valley. Neither Morgan Stanley nor Goldman has an iPad application for clients to manage their portfolio. Last year, a Merrill adviser met with a start-up employee in her 20s who brought along her parents. They discussed going to grad school or buying a home.

But Wall Street is trying to adapt its strategy.

Merrill executives are seeking advice from company employees under 30 on how to shape pitches. Barclays is pairing older wealth managers with young associates, who tend to be more familiar with social media.

“There are insights that one generation has — about technology, social media, networking — that another one may not fully appreciate,” said Mitch Cox, head of the Americas for Barclays’ private wealth management arm.

With a younger clientele, informational sessions focus on the basics, including buying a first home, paying off debt or building a portfolio.

Merrill offers “boot camps,” that explain fundamentals like mutual funds and dividends. The firm is building such a program for Facebook employees timed to the I.P.O., according to people briefed on the plans.

“It’s a big business opportunity,” said Greg Vaughan, a managing director at Morgan Stanley’s Menlo Park office. “There’s a lot of wealth being created out here.”

Evelyn M. Rusli reported from Palo Alto, Calif., and Ben Protess from New York.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=54059e2348211226689b8fb0fd81622c