Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

The continuing debate over the Affordable Care Act and the commentary on this blog have convinced me that nothing can ever unite Americans on their vision of an ideal health system.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

We need different health insurance systems for different Americans. I mean by this not Americans who differ by age or ability to pay but Americans with different notions of a just society.

This is where Germany’s approach to a health insurance system can serve as an inspiration.

Germany’s population of close to 82 million is served by two distinct health insurance systems:

1. The Statutory Health Insurance System, founded in 1883 by Otto von Bismarck and constantly amended over the ensuing century.

Germany’s statutory health insurance system is the oldest in the world and has served as a model for many other countries in Europe, Latin America and Asia. In Germany the system consists of 154 (as of July 2011) autonomous, private, nonprofit sickness funds among which individuals can choose freely, which means that the funds compete with one another.

Unlike Americans, who often are limited to networks of providers, Germans have complete freedom of choice of provider under the statutory system.

The sickness funds now provide very comprehensive health insurance to more than 85 percent of the population. They are overseen by boards composed of employers and unions. Their management, however, is strictly regulated by the law, as amended.

Germany’s private insurance system is composed of 46 health companies that are operated on commercial principles, albeit under federal regulations, and provide comprehensive coverage to another 11 percent of the population, including all civil servants, although individuals and families in the statutory system often purchase supplementary coverage (for superior amenities or items not covered by the statutory system).

In 2009, these companies accounted for less than 10 percent of total national health spending in Germany, which amounted to $4,200 per capita in purchasing power parity, slightly more than half of American spending of $7,900, even though Germany’s population is much older on average than ours.

The remainder of Germany’s population (police officers, the military and others) have their own coverage.

Financing the Statutory System

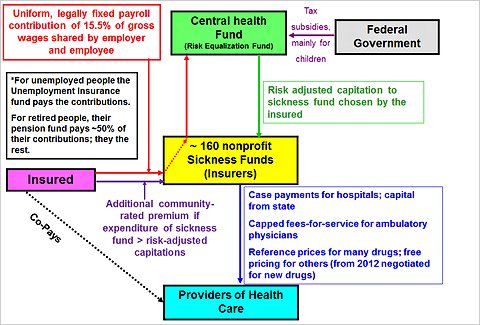

The statutory system is financed on the principle of social solidarity, that is, strictly on the basis of ability to pay. The sketch below illustrates this flow of funds:

Employees covered by the statutory system must pay a nationally uniform contribution to the sickness fund of their choice of 8.2 percent of their gross wages (and pensioners 8.2 percent of their pensions), while employers (or pension funds) must contribute 7.3 percent, for a total contribution of 15.5 percent of gross wages up to a maximum gross wage (or pension) of 44,550 euros, about $59,700. Earnings above that threshold are not subject to this levy.

Unemployed people pay premiums in proportion to their unemployment compensation, unless they are long-term unemployed, in which case the federal government pays the sickness fund a fixed per-capita payment.

The total contribution paid to a sickness fund covers the employee (or pensioner) and any nonworking dependents, except children, for whom insurance coverage is tax-financed by the federal government.

To equalize actuarial risk among the competing sickness funds, Germany operates a national risk-equalization fund (the Gesundheitsfond). The premium contribution rates paid by employees and employers to a sickness fund are immediately transferred to this central fund.

If the employee (or pensioner) then chooses sickness fund A, the central fund pays the chosen sickness fund a capitation that is risk-adjusted for that employee (or pensioner) and the nonworking dependents. The risk-adjustment formula used for that purpose includes age, gender and about 80 indicators of morbidity.

Financing Commercial Insurers

Private insurers draw their financing from per-capita premiums that reflect a person’s age, gender and health status at the time of enrollment but thereafter can be raised only as a function of age, not changing health status. Separate per-capita premiums are levied on dependents in a family.

Recent federal legislation has forced private insurers to levy on younger people higher premiums than their actuarial risk can justify to build up an old-age reserve, thus preventing premiums from climbing too rapidly with age.

Recently the private system has come under a number of new regulations. For more detail on these, readers are referred to the links provided above.

Closing the Door to Statutory Insurance

By law, every German must have coverage for a prescribed benefit package. German employees and pensioners earning less than 49,500 euros ($66,350) per year (in 2011) are compulsorily insured under the statutory system.

Employees and pensioners above that threshold are free to opt out of the statutory system and purchase private, commercial coverage, but if they do, they cannot ever return to the statutory system unless they are paupers. The intent is to minimize gaming of the insurance system by individuals.

It is this feature that intrigues me, as it has my colleague Paul Starr, in his proposed alternative to an individual mandate to be insured.

What if Americans at, say, age 26 (beyond which they can no longer be included on their parents’ insurance policy) or even as late as age 30 were offered the choice of:

1. joining the community-rated health insurance offered through the insurance exchanges called for in the Affordable Care Act;

2. remaining in a private insurance system that is free to charge in any year “actuarially fair” premiums, that is, premiums that reflect the applicant’s projected health status and spending for that year and is free to refuse issuing a policy altogether;

3. simply self-insuring, by remaining uninsured?

For want of better terms, we might call the exchange system the “social insurance track” (because it leans heavily toward social insurance) and the second and third options the “rugged individualist tracks,” because they cater to Americans with individualist preferences.

For people choosing the rugged individualist tracks, Professor Starr proposes to shut the door to the social insurance track for only five years.

I believe his stricture is too weak and propose instead to follow the German example by shutting the door permanently to social insurance to any individual who chose one of the two rugged individualist tracks, unless such individuals were truly pauperized. A return then would have to be allowed, because, for better or for worse, our civic sentiments preclude letting anyone – even a myopic rugged individualist — die for want of critically needed health care.

Admittedly, this approach would confront young Americans with a serious life-cycle choice. But life-cycle choices are made all the time, and choices do have consequences that people in their mid-20s should be mature enough to think about. Adults must realize that individual freedom has its price.

The American health insurance system now is structured as a paradise for clever adolescents, inviting gaming of many sorts that makes sensible health policy almost impossible. It is time to move away from such a system.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=9a721a9eb5ca092fe1935c8b2dbaf360