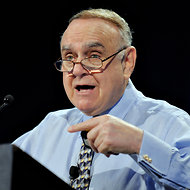

Peter Foley/Bloomberg NewsLeon Cooperman says he did not write “on behalf of Wall Street.”

Peter Foley/Bloomberg NewsLeon Cooperman says he did not write “on behalf of Wall Street.”

Leon Cooperman, a 68-year-old Wall Street veteran, says he is for higher taxes on the wealthy. He would happily give up his Social Security checks. He voted for Al Gore in 2000. He says the special treatment of investment gains, or so-called carried interest, for private equity and hedge fund managers is “ridiculous.” He says he even sympathizes, at least to some extent, with the Occupy Wall Street protesters.

And yet, Mr. Cooperman, a man with a rags-to-riches background who worked at Goldman Sachs for more than 25 years in the 1970s and 1980s before starting his own hedge fund, Omega Advisors, which has minted him an estimated $1.8 billion fortune, is waging a campaign against President Obama.

Last week, in a widely circulated “open letter” to President Obama that whizzed around e-mail inboxes of Wall Street and corporate America, Mr. Cooperman argued that “the divisive, polarizing tone of your rhetoric is cleaving a widening gulf, at this point as much visceral as philosophical, between the downtrodden and those best positioned to help them.”

He went on to say, “To frame the debate as one of rich-and-entitled versus poor-and-dispossessed is to both miss the point and further inflame an already incendiary environment.”

DealBook Column

View all posts

The letter comes as President Obama is planning to give a speech on Tuesday in Osawatomie, Kan., about the economy and the middle class, following in the path of President Theodore Roosevelt, who campaigned a century ago in that very city against the wealthy and big business.

Mr. Cooperman’s complaint has less to do with the substance of taxing the wealthy than it does the president’s choice of words in promoting it, an emphasis that he says is “villainizing the American Dream.”

While many executives have complained about what they perceive as the president’s antibusiness bent, Mr. Cooperman’s letter has gained credibility and attention in political and business circles because of his own seemingly liberal stances on taxes and the like.

Mr. Cooperman, in an interview, said he had been deluged with hundreds of e-mails and phone calls about the letter, “99.9 percent of it positive.”

“I came from nothing,” he said, explaining how he grew up in the Bronx and went to P.S. 75. “I have lived the American Dream. I don’t want to be constantly attacked.”

He was quick to say that he did not write the letter “on behalf of Wall Street.” Indeed, Mr. Cooperman’s view of the financial industry is dimmer than you might expect from someone who made his fortune in it. “Wall Street screwed up,” he said matter-of-factly. “They did things they shouldn’t have.”

He said he decided to write the president a letter because he became convinced that Mr. Obama was “villainizing success.” He added, “We are supposed to admire success.”

Of course, his letter has not gone over well with some audiences — he has been called a “whiner” and worse. On Daily Kos, a left-leaning commentary site, one member wrote: “He simply embarrasses himself with this rant, and seems more interested in complaining about the points Obama is making that aren’t in his personal economic interests than in providing any real solutions to our problems.”

Mr. Cooperman acknowledged that he had received at least one negative e-mail. “I got one that said, ‘Be very careful when you start you car in the morning because there might be a bomb in it.’ ” He tried to laugh it off.

Some critics of Mr. Cooperman’s letter say President Obama has not been hard enough on big business and questioned what it was that the president has said that has drawn the ire of the business community.

“What pushed me over the fence was the president’s dialogue over the debt ceiling,” Mr. Cooperman said, explaining that just when it seemed like a compromise was near, President Obama went on national television and pressed harder on “millionaires and billionaires,” a phrase that has stuck in the craw of many of the elite. For example, Mr. Cooperman zeroed in on what he described as the president’s belittling remarks about taxing the wealthy: “If you are a wealthy C.E.O. or hedge fund manager in America right now, your taxes are lower than they have ever been. They are lower than they have been since the 1950s. And they can afford it,” the president said back in June. “You can still ride on your corporate jet. You’re just going to have to pay a little more.”

The president’s tone can be debated. Some people would argue it is simply factual, others contend that it is dripping with derision.

Mr. Cooperman acknowledges that, in the debt ceiling debate this summer, it was as much the fault of Republicans and House Speaker John Boehner’s inability to gain support for a compromise as it was the Democrats that a deal did not get done. And Mr. Cooperman accepts that taxes are indeed at record lows.

But he says the president could do a better job of pressing for higher taxes on the rich without “the sense that we’re bad people.” He added, “I pay federal income tax. I don’t have any tax dodges.” He paused, before saying, “Most people I know are prepared to pay more in taxes as long as it’s spent intelligently.”

He added that he understood the politics of what he called “class warfare.” “Now, I am not naïve. I understand that in today’s America, this is how the business of governing typically gets done — a situation that, given the gravity of our problems, is as deplorable as it is seemingly ineluctable.”

Mr. Cooperman said he personally had been advocating adding a 10 percent tax surcharge on all incomes over $500,000 for the next three years. He also advocates that the military “get out of Iraq and Afghanistan” and that every soldier should be “given a free four-year education.” His personal “platform” — he insists he is not running for any office — also includes setting up a peacetime Works Progress Administration to rebuild United States infrastructure; freezing entitlements; raising the Social Security retirement age for full benefits to 70 “with an exception for those that work at hard labor”; adding a 5 percent value-added sales tax; and “tackling health care in a serious way,” among other things.

Mr. Cooperman, who recently signed the Giving Pledge, Bill Gates’s and Warren Buffett’s effort to press the world’s billionaires to give away at least half of their wealth, said he felt he came into his money honestly and said proudly, “I spend more than 25 times on charity what I spend on myself.” Asked whether he had received any response from the president for his letter, he replied with a chuckle, “I’m not optimistic I’ll hear from him.”

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=9094c3e3753efc8414a28dc25326e28d