Richard Perry/The New York TimesSony’s entertainment unit includes a film studio and one of the largest music labels in the world, featuring artists like Taylor Swift.

Richard Perry/The New York TimesSony’s entertainment unit includes a film studio and one of the largest music labels in the world, featuring artists like Taylor Swift.

TOKYO — Devil. Vulture. Saboteur.

All these words have been used to greet Western investors who have agitated for change in Japan’s clubby and complacent corporate culture. As the hedge fund billionaire Daniel S. Loeb prepares to take on Sony, he may find the same hostility from the company that at one time single-handedly defined premium quality in entertainment and electronics.

How Sony, and Japan, react to the demands brought by Mr. Loeb on Tuesday could become a test of how far the country has come in making good on promises to open up to more foreign investment and, more important, change.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who took office in December, has promised to shake up corporate Japan by removing onerous regulations, protections and inflexibilities that have sapped profitability and hampered serious revamping.

Related Links

Interactive Timeline: The Playbook of an Activist Hedge Fund Manager

Interactive Timeline: The Playbook of an Activist Hedge Fund Manager- Sony Meets Outspoken Activist Investor, but Courtesy Reigns

- American Investor Targets Sony for a Breakup (May 14, 2013)

Graphic: Sony Swings to a Profit

Graphic: Sony Swings to a Profit

Investors initially are cheering Mr. Loeb’s efforts. Sony’s shares rose nearly 10 percent in the United States to close at $20.76 on Tuesday. The reaction among those who matter — Sony’s managers — has been muted.

Almost no local media outlets carried the story of Mr. Loeb’s hand-delivered list of demands to Sony on Tuesday, hours after those demands had been made public. Sony itself issued only a curt statement, saying its entertainment businesses were “not for sale.”

“Sony is an icon. Until now, it hasn’t had a fellow like this coming in and making demands in public,” said Nicholas Benes, a former Wall Street banker who now advises Japanese companies on corporate governance. “But now he comes in with guns blazing. This hasn’t quite started off right, you might say.”

Activist investors like Mr. Loeb’s fund, Third Point, might seem like natural allies in that mission to prod Japan’s corporations toward change. Mr. Loeb’s demands for Sony’s management center on bringing more focus to its sprawling business, something analysts have long called for, partly by spinning off a part of its entertainment arm. And Mr. Loeb cites Mr. Abe’s promised economic reforms as a big reason behind his recent interest in Japan.

Nowhere has revamping been so painfully needed as in Japan’s electronics industry, where six major manufacturers, including Sony, still produce flat-panel televisions, mostly at a loss. Better labor mobility might make companies more reluctant to close or spin off money-losing operations and focus on profitable lines of business.

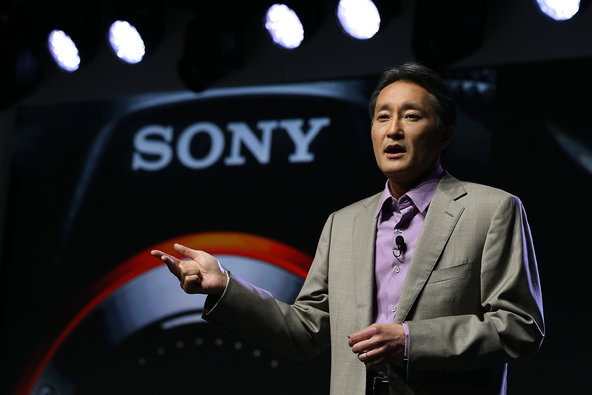

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesKazuo Hirai, the chief of the entertainment and electronics colossus Sony.

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesKazuo Hirai, the chief of the entertainment and electronics colossus Sony.

American activist investors have, however, met with frustration in the efforts to add value at other companies. T. Boone Pickens, who acquired a minority stake in the auto parts company Koito Manufacturing in 1989, pressed its management for better dividends and a seat on its board. But the little manufacturer dug in its heels. Shareholders heckled him with anti-American taunts at its annual shareholders meeting; the press branded him an opportunistic vulture. Koito’s president refused even to meet the Texan magnate.

“O.K., Koito; I give up,” Mr. Pickens declared in a statement two contentious years later, before selling his entire stake. “The heck with Japanese business.”

Mr. Loeb is unlikely to get such openly hostile treatment from Sony, now that he is a significant investor with a 6.5 percent stake in the company. After all, it is 2013, and Sony, unlike Koito, is a global, savvy firm.

Gerhard Fasol, president of the Tokyo technology consulting firm Eurotechnology Japan, said Mr. Loeb had probably studied past unsuccessful approaches to Japanese companies.

“My guess is that he learned from the mistakes those activist investors made and was advised to tone things down,” Mr. Fasol said. Mr. Loeb makes a point of starting the note with praise for Mr. Hirai and his commitment to change.

Mr. Loeb has suggested that Sony take 15 to 20 percent of the entertainment unit public by offering current Sony shareholders the opportunity to buy shares. The unit includes a leading film studio and one of the largest music labels in the world, featuring artists like Taylor Swift. A spinoff could lead to higher profit margins, while helping to revive the core electronics business, Mr. Loeb argues.

Yet even though many inside and outside Japan recognize that Sony’s divisions need some shaking up, a hedge fund manager like Mr. Loeb may not be the one who is ultimately successful.

Active investing has long been seen in Japan as a dangerous, alien practice led by foreigners, or cheeky locals who dare imitate them. And in past cases, lenders, bureaucrats, other shareholders and even rivals have swooped in to rescue companies from investors’ talons. Of the 23 hostile takeover bids in Japan since 2000, only 7 have been successful, according to Dealogic

The cross-shareholdings of Japanese companies — with close ties to their main bank and other companies, known as keiretsu — have helped foster an environment where hostile takeovers are rare and shareholders are docile supporters.

But in the mid-2000s, when Japan seemed to stage a nascent recovery, the country attracted a wave of what company executives came to call “investors who say things.”

In 2006, when Steel Partners, an American fund, took out a stake in the noodle maker Myojo Foods, the company flatly refused to entertain a proposal for a management buyout, accusing the fund of trying to sabotage the company’s future for short-term gain. When Steel Partners instead started a takeover bid, Myojo ran into the arms of its noodle archrival, Nissin Foods, which bought it out.

Undeterred, Steel Partners aimed at another food company, this time a condiment maker called Bull-Dog Sauce, and accumulated a 10 percent stake in 2007. Not satisfied with the management’s reluctance to expand overseas to make up for a waning domestic market, the fund started a tender bid for the rest of the company. This time, it was thwarted by a landmark ruling by Japan’s Supreme Court supporting the use of “poison pill” defenses in Japan.

The media followed the food companies’ tribulations with much gusto, berating the brash manners of Warren Lichtenstein, chief of Steel Partners. The public broadcaster, NHK, showed a drama series, “Vulture,” about an American investment firm that snaps up troubled companies.

“Is he a devil, or a savior?” the narrator asked in a booming voice.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/05/14/japan-braces-for-challenge-by-u-s-investor/?partner=rss&emc=rss