New America Foundation Stephen Burd, a senior policy analyst at the New America Foundation.

New America Foundation Stephen Burd, a senior policy analyst at the New America Foundation.

“With their relentless pursuit of prestige and revenue, the nation’s public and private four-year colleges and universities are in danger of shutting down what has long been a pathway to the middle class for low-income and working-class students,” writes Stephen Burd, a senior policy analyst at the New America Foundation, in a new report that’s getting considerable attention.

Mr. Burd uses data from the Education Department to argue that many colleges “are engaged in an elaborate shell game.” With Congress having recently increased the size of Pell Grants, a large federal aid program for lower-income families, colleges are redirecting their own aid money toward higher-income students. The goal of the colleges, he says, is to attract the high-scoring students who lift a college’s ranking and prestige.

Yet with list-price tuition growing rapidly, lower-income students, Mr. Burd writes, are left to pay more. He adds: “This is one reason why even after historic increases in Pell Grant funding, the college-going gap between low- income students and their wealthier counterparts remains as wide as ever.”

He uses the federal data to name colleges that are charging high net prices — that is, even after taking into account financial aid – for low-income students. The average net price for first-year, full-time students with family incomes of $30,000 or less at New York University, for instance, is a whopping $25,462. In effect, N.Y.U. is asking such a family to devote all of its income to college.

The comparable average at the University of Miami is $21,415. At Southern Methodist University, in Dallas, it is $14,040. At Penn State, a public university, it is $16,839. On the other end of the spectrum are, among others, Georgia Tech ($0), Caltech ($310) and Amherst College ($448).

Mr. Burd and I recently conducted a conversation by e-mail, and a lightly edited transcript follows.

Many people — myself among them — have long seen some advantages in the so-called high-tuition, high-aid model, in which a college charges a substantial list price but also awards large amount of aid. Such a system ensures that high-income families, who can afford college, pay for it at a time when college budgets are stretched and income inequality is high. It is an akin to a progressive system of taxation. You are skeptical of that model, though. Why?

I completely understand the appeal of the high-tuition, high-aid model in a theoretical sense. However, the net price data that I examine show that in states that are following this model, such as Pennsylvania and South Carolina, the neediest students are facing net prices that are more than double what they are being in low-tuition states such as North Carolina.

I think what happens sometimes is that states go to the high-tuition model but don’t follow through on the high-aid side of the equation. It also appears to be the case that the high aid is not necessarily going to low-income students — but is instead being redirected toward wealthier students.

Do you see any exceptions — state universities that charge a high list-price tuition but provide large amounts of aid to low-income students and enroll substantial numbers of them? There seem to be at least a few private colleges following that model, including Amherst, Haverford and Pomona.

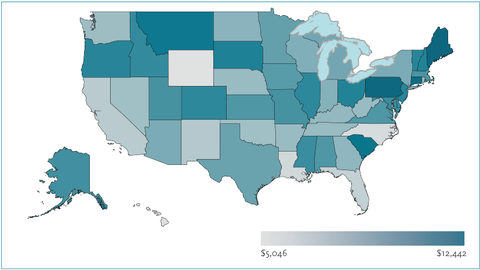

I didn’t dig as deep on the public college side to parse that out. There still are a significant number of state universities that enroll a substantial share of low-income students and charge them a manageable net price. Having said that, the public institutions that I found are cheapest for low-income students are in low-tuition states, such as California, Florida, Louisiana, and North Carolina. The schools that were most expensive for low-income students are in high-tuition, high-aid states such as New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina.

Sources: U.S. Department of Education and New America Foundation. What the lowest-income students pay to attend public colleges in each state. State-by-state data represent the average net price that first-time, full-time students with family incomes of $30,000 or less are charged, after all grant and scholarship aid is taken into account, to attend public colleges in their home states. The net price data are from the 2010-11 academic year.

Sources: U.S. Department of Education and New America Foundation. What the lowest-income students pay to attend public colleges in each state. State-by-state data represent the average net price that first-time, full-time students with family incomes of $30,000 or less are charged, after all grant and scholarship aid is taken into account, to attend public colleges in their home states. The net price data are from the 2010-11 academic year.

There are definitely some schools in high-tuition, high-aid states that provide generous amounts of need-based aid — such as the University of Virginia and the University of Michigan. But these schools don’t tend to enroll a substantial share of low income students.

Yes, that seems to be one of the big mysteries from your report. You have two tables listing excellent colleges that are affordable for low-income students yet enroll very few of them, including Virginia, Michigan, the University of Delaware, Caltech and Washington University in St. Louis. Studies have made clear that large numbers of high-performing, low-income students exist. Why don’t they make it to these colleges? Do you think the colleges want to attract them?

I think that there are some schools that genuinely want to attract these students – and some like Amherst, Vassar, M.I.T., etc., that do a very good job of it. There are others that appear to be much more interested in attracting the “best and the brightest” and wealthiest students to improve their rankings and increase their revenues.

I do think that schools like Harvard and Virginia are genuinely interested in attracting more low-income students but have had trouble finding them. The excellent report you’ve written about by Christopher Avery and Caroline Hoxby shows that colleges don’t always look in the right places to find these students. And many of these students — even those with the most impressive academic records — don’t even think about applying to these schools because they don’t think they can afford them, among other reasons.

Imagine the president or a governor called you into his or her office and said, “O.K., how do we change policy to improve matters.” What would you say?

I can’t believe that hasn’t already happened!

Because of my background covering federal student aid, I’ve mostly thought of this from the perspective of the federal Pell Grant program, which provides nearly $35 billion a year to help low-income students pay for college. Right now this money goes to colleges without any strings attached. I think that’s got to change to ensure that colleges are doing their part to remove the financial barriers that prevent low-income students from enrolling in and completing college.

At the New America Foundation, we have recommended that the government take a carrot-and-stick approach. The carrot is to help schools that don’t have the resources to keep down the net prices of the low-income students they serve. The plan would offer Pell bonuses to financially strapped public and private four-year colleges that serve a substantial share of Pell Grant recipients and graduate at least half of their students school-wide. The goal would be to help these schools boost their institutional aid budgets and bring down the net prices they charge the neediest students.

The stick is for wealthier colleges that have chosen to divert their aid to try to buy the best and/or wealthiest students. These schools would be required to provide additional need-based aid, to help the lowest-income students, in exchange for the Pell dollars they receive.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/10/q-a-on-the-shell-game-of-college-aid/?partner=rss&emc=rss