CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

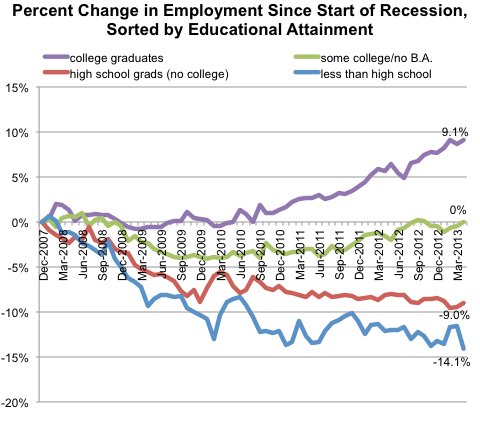

Despite all the questions about whether college is worth it or not, college graduates have gotten through the recession and lackluster recovery with remarkable resilience.

The unemployment rate for college graduates in April was a mere 3.9 percent, compared to 7.5 percent for everyone else. And among all segments of workers sorted by educational attainment, college graduates are the only group that has more people employed today than when the recession started.

Here’s a look at how employment has changed since the recession officially began, in December 2007, sorted by education.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Data refer to workers age 25 and older.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Data refer to workers age 25 and older.

The number of college-educated workers with jobs has risen by 9.1 percent since the beginning of the recession. Those with a high school diploma and no further education are the near mirror image, with employment down 9 percent on net. Workers without even a high school diploma have seen their employment levels fall 14.1 percent.

Finally, for those with some college but no bachelor’s degree, employment fell during the recession and is now back to exactly where it began: There were 34,992,000 workers with some college employed in December 2007, and there are 34,992,000 in the same boat today

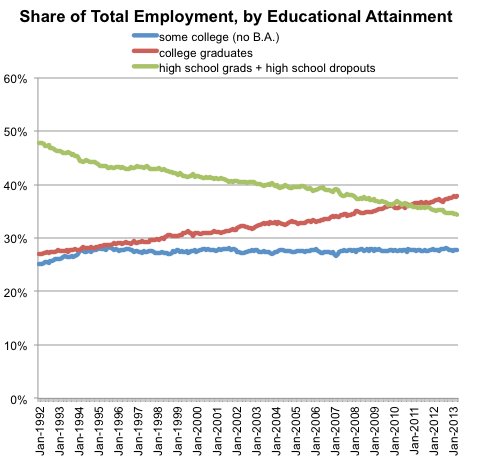

In other words, college-educated workers have gobbled up all of the net job gains. In fact there are now more employed college graduates than there are employed high school graduates and high school dropouts put together.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Data refer to workers age 25 and older.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Data refer to workers age 25 and older.

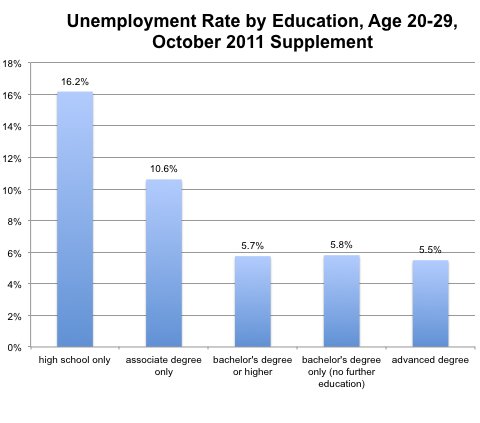

It’s worth noting, too, that even young college graduates are finding jobs, if you look at the most recent cut of data on this subgroup (which is from 2011).

As I wrote in an earlier post, in 2011, the unemployment rate for people in their 20s with college degrees or more education was 5.7 percent (for those whose highest credential was no more than a bachelor’s, the number was 5.8 percent). For those with only a high school diploma or G.E.D., it was more than twice as high, at 16.2 percent.

Sources: October School Enrollment Supplement, Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics; Thomas Luke Spreen.

Sources: October School Enrollment Supplement, Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics; Thomas Luke Spreen.

Of course, just because college graduates have jobs doesn’t mean they have “good” jobs.

There is ample evidence that employers are hiring college-educated workers to perform jobs that don’t actually require college-level skills — positions like receptionists, file clerks, waitresses and car rental agents. This form of underemployment might be one reason why we see so much growth in employment among college graduates despite the fact that the bulk of the jobs created in the last few years have been low-wage and low-skilled.

Clearly positions in retail and food services are not the best use of the hard-earned (and expensive!) skills of college-educated workers. But at least those graduates are finding work and income of some kind, unlike their less-educated peers. And as the economy improves, college graduates will be better situated to find promotions to jobs that do use their more advanced skills and that pay better wages.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/03/life-is-o-k-if-you-went-to-college/?partner=rss&emc=rss