Laura D’Andrea Tyson is a professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and served as chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Bill Clinton.

The economy is continuing to recover from its deepest recession since the Great Depression, but the pace of recovery is frustratingly slow. The question is why, and the answer has profound implications for fiscal policy and for the debate over deficit reduction and economic growth that has transfixed Washington.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Since 2010, annual growth of gross domestic product has averaged about 2.1 percent. This is less than half the average pace of recoveries from previous recessions in the United States since the end of World War II, according to a recent study by the Congressional Budget Office. Both potential G.D.P., a measure of the economy’s underlying capacity, and actual G.D.P. have grown unusually slowly compared with previous recovery periods.

Slow G.D.P. growth has meant slow growth in employment. Payroll employment has been expanding at a rate of about 150,000 jobs per month during the last two years, only slightly above the growth of the labor force. Employment growth has been largely consistent with overall G.D.P. growth and with the “jobless” pattern of the 1990-91 and 2001 recoveries.

In both this recovery and the previous two, the rebound in employment growth has been weaker and later than the rebound in G.D.P. growth. But G.D.P. growth in the current, jobless recovery has been slower. Another salient difference is that the loss of jobs in the most recent recession was more than twice as large as in previous recessions, so a slow recovery has also meant a much higher unemployment rate.

Why has G.D.P. growth been so tepid compared with previous recoveries? Most economists believe that weak aggregate demand is the primary culprit. The 2008 recession resulted from a systemic financial crisis rooted in an asset bubble that gripped the housing market with particular ferocity. Private sector demand contracts sharply and recovers slowly after such crises.

The large and persistent decline in private-sector demand that began the 2008 recession and that explains the painfully slow recovery is apparent in the private-sector financial balance — net private saving, the difference between private saving and private investment.

The private-sector financial balance swung from a deficit of −3.7 percent of G.D.P. in 2006, at the height of the boom, to a surplus of about 6.8 percent in 2010 and about 5 percent today. This represents the sharpest contraction and weakest recovery in private-sector demand in the post-World War II period.

Growth in two components of private demand — consumption and residential investment — has been especially slow in this recovery compared with the average for previous recoveries. This is not surprising.

Residential investment is still depressed as a result of overbuilding during the 2004-8 housing boom and the tsunami of foreclosures that followed. Large losses in household wealth, deleveraging from excessive debt, weak growth in wages and household income, and a decline in labor’s share of national income to a historic low have combined to constrain consumption growth. Wobbly consumer confidence and the concentration of most income gains at the top of the income distribution have also contributed.

The recovery of business investment demand has followed a different pattern. Indeed, the growth of business investment has been slightly stronger during the current recovery than the average for previous ones. But after plummeting to new lows during the recession, the ratio of net business investment to G.D.P. remains depressed by historical standards. Lower net investment compared with the economy’s capital stock is a major reason that the growth rate of potential G.D.P. has been so slow.

Throughout the recovery, business surveys have identified lackluster customer demand and weak sales prospects as the primary factors holding down business investment. Business confidence has remained subdued as a result of uncertainty about the future growth of markets both at home and abroad and more recently about the future course of United States fiscal policy.

Limits on credit availability were also significant deterrents to investment, especially by small and medium-size firms at least through 2010, when banks began to ease their commercial loan terms.

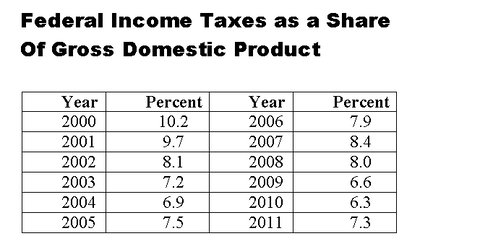

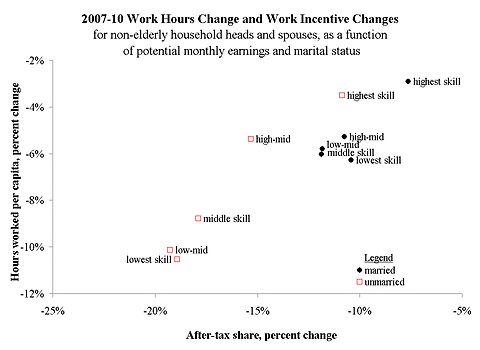

Weak investment demand cannot be explained by low profits and high taxes: the profit share of national income has hit a historic peak and taxes on investment income are at historic lows.

Another factor contributing to the slow pace of the current recovery relative to previous recoveries has been the relatively weak growth of government spending on goods and services by both state and local governments and by the federal government.

Indeed, the contraction in state and local government spending and the associated decline in public-sector employment have been major headwinds restraining G.D.P. growth.

The increase in federal government purchases of goods and services in the 2009 stimulus bill mitigated but did not offset the effects of weak private-sector demand through 2010. But since then, the slowdown in such purchases has been a drag on G.D.P. and employment growth.

After three years of recovery, the economy is still operating far below its potential and long-term interest rates are hovering near historic lows. Under these circumstances, the case for expansionary fiscal measures, even if they increase the deficit temporarily, is compelling.

A recent study by the International Monetary Fund finds large positive multiplier effects of expansionary fiscal policy on output and employment under such circumstances.

And more output and employment now would mean higher levels in the future, because stronger demand now would encourage more private investment and stem the loss of skills and productivity resulting from long-term unemployment and the drop in the labor force participation rate.

The rationale for expansionary fiscal policy is particularly compelling for federal investment spending in areas like education and infrastructure that have large multiplier effects on the current level of output and employment and strong returns over time.

By the same logic, the $600 billion of revenue increases and spending cuts scheduled for next year — the so-called fiscal cliff — would have large negative effects on demand, output and employment and would reduce future potential output as well.

The fiscal cliff packs a powerful punch: there will be 3.4 million fewer jobs by the end of 2013 if Congress allows these policies to take effect.

The economy does not need an outsize dose of fiscal austerity now; it does need a credible deficit-reduction plan to stabilize the debt-to-G.D.P. ratio gradually as the economy recovers. As I contended in an earlier Economix post, the plan should have an unemployment-rate target or trigger that would postpone deficit-reduction measures until the target is achieved. (In a move that signals its abiding concern about the recovery’s strength and resilience, the Federal Reserve has just announced an unemployment-rate target for monetary policy, committing to keep short-term interest rates near zero until the unemployment rate falls to 6.5 percent.)

The goal of deficit reduction is to ensure the economy’s long-term growth and stability.

It would be the height of fiscal folly to kill the economy’s painful recovery from the Great Recession in pursuit of this goal.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/14/the-trade-off-between-economic-growth-and-deficit-reduction/?partner=rss&emc=rss