Staying Alive

The struggles of a business trying to survive.

I read Ami Kassar’s recent post on sloppy bookkeeping with interest because I spent so many years struggling to figure out why I was always running out of money.

I do have an excuse: I started my business a long time ago, in 1986, and many of the business tools we take for granted didn’t exist, or at least weren’t accessible to a tiny company like mine. Obviously, I had no Internet, e-mail, cellphone or Web site. It may be hard to imagine, but personal computers were just getting started, spreadsheets were primitive, and QuickBooks was years in the future. So I got off on the wrong foot, and it took me a long time to recover.

Fast forward 26 years, and I have put in place a reasonable set of accounting tools and learned to do a little spreadsheet writing. I now do my bookkeeping and accounting with QuickBooks. I calculate my pricing for custom work with Excel. And I track cash flow using Google spreadsheets. With these, I can do all of the standard accounting tricks, which mainly look backward in time at what happened to my money, and even look a little into the future to predict short-term cash flows. Until last week, though, I had never created a budget for the coming year.

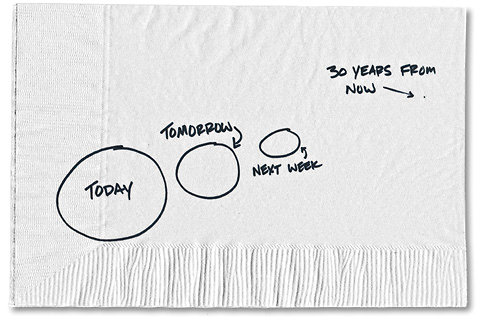

I have found it to be much easier, using QuickBooks, to look backward rather than forward. Maybe this is because accounting is geared toward actual transactions and is less equipped to handle the future. Maybe it is because the conventions of accounting date back hundreds of years and just haven’t been updated to take into account the ubiquitous spreadsheet, which allows for easy modeling of future cash flows. Or maybe it is because I’m simply uneducated with regard to the accounting software I use and can’t figure out how to make QuickBooks do my bidding.

If you don’t find those excuses to be convincing, and you shouldn’t, here is a better one: I was very, very busy with selling until recently, when I handed off that responsibility to my employees. Suddenly, I find myself with time to think about things, and I’m doing projects that I should have done years ago. One of them was to try to figure out whether I would be able to afford to pay myself a decent salary this year and also hire a couple of workers. So I decided to do a budget for 2013.

I had just run a profit-and-loss report out of QuickBooks, comparing 2011 and 2012, to see how much I was spending on materials and whether there had been any surprise expenditures. It was interesting to consider the entire chart of accounts, which for my small factory has more than 100 main accounts and subaccounts. It occurred to me that it would be simple to export the current P.L.report as an Excel sheet and use the existing chart of accounts as budget line items for the following year. That way, I would not forget to include obscure yet expensive expenditures like leasehold improvement depreciation. With two years’ spending in each category, it would give me a good start toward figuring out reasonable amounts to budget for the coming year. And I could, with a little effort, convert some of the cells from straight numbers to formulas that varied with income, so that I could model alternative situations.

I’m not a spreadsheet genius, but I have learned enough to accomplish my goals: how to write simple formulas and how to make a cell in one sheet refer to a result in another. With that level of mastery, I was able to set up the budget so that the material spending varied as a percentage of revenue, with the baselines determined by averaging the previous two years. I was also able to assemble a separate sheet that had a complete model of my employee labor costs, including pay rates; forecasts of hours of regular time and overtime for each worker; the federal, state, and unemployment taxes that their wages would generate; and their retirement plan contributions.

Because this is so complicated, I have made a copy of the original — with the numbers scrambled a bit for the sake of my privacy — and posted it here. It’s a Google Doc and shows only the values of the cells, not the formulas, so I added some comments to clarify the relationship between the budget and labor sheets. Also, the chart of accounts is ours, and your results may vary. I don’t expect anyone to copy this exactly, but it will give you an idea of one way to set up a budget and make it into a forecasting model.

When I finished my budget using my real projections — including a rise in revenue to $2.4 million, a reasonable salary for myself, what I expected to pay all of my people, and expenditures for materials proportional to the rise in revenue rise — I found that I would have only $54,000 left over. That is pretty slim pickings out of $2.4 million. It wouldn’t take much of a revenue shortfall or unexpected expense to wipe it out entirely.

Of course, I could make that number jump by cutting employee salaries, or my own salary. I did budget $73,500 for some projects I expected to complete: a second Web site and some computer and machinery purchases. But I could choose not to spend that money and improve my bottom line. The most promising source of savings, though, is materials. I’ll be taking a hard look at some of those expenditures to see whether we cannot buy more efficiently.

After doing all of this, I went back to QuickBooks to take a look at the built-in budgeting tool. There is one there, but I found it disappointing. (Here is a reasonably succinct explanation of how to use it.) What it does not do is let you import the previous year’s actual spending to use as a starting point, and it also does not seem to allow you to enter formulas to make different accounts dependent on each other, which is why I much prefer using a spreadsheet. I wish that there were a simple and painless way to set a budget, but — as with so much of the financial side of running a business — there are not any shortcuts.

Getting back to Ami’s post, it covered all of the reasons to keep your books up to date. And I have nothing to add — except to say that once I started putting in the time every week to see where my money was going, I suddenly had more of it. Not always as much as I wanted, but enough to build up a decent amount of working capital over the last three years. Now, with my budget in hand, I hope to do even better in 2013.

Paul Downs founded Paul Downs Cabinetmakers in 1986. It is based outside Philadelphia.

Article source: http://boss.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/12/why-i-finally-decided-to-make-a-budget/?partner=rss&emc=rss